The Windhook Interview—Jason Kelly

Today's interview marks our one year anniversary at Outside the Lines! To mark the occasion we bring you Jason Kelly. Jason is an old friend as you will see. He is a writer who lives in Japan and publishes a weekly subscription newsletter for stock market investors. He's also a novelist and creative thinker and humanitarian activist who has crafted a lucrative and satisfying lifestyle of his own. It's a long interview, but there is lots of ground to cover.

Also, this is the first interview that we have conducted in Guy Rathbun's studio. We are doing this when possible so that Guy will have full access to studio quality interview recordings for his new show, Designing a Creative Life on prx.org. So a new feature in this interview is that Guy's voice joins Michael and Peggy's voices as interviewers. Watch for Guy's show, based on this interview, in about a week. We will have a link to it in our next edition of Outside the Lines.

Guy: Jason, it's great that you could join us for this discussion. What you have done is nothing short of wonderful, not only with Socks for Japan, but the financial advice you have given over the years.

Jason: Thank you.

Guy: I want to go back to your earliest days when you wrote a little financial book. Your life changed. Tell us the story behind that.

Jason: Yeah, it really did. I actually met Michael at IBM, which was my first job out of college. I was really happy to get that job, because I had studied English literature and writing in college at the University of Colorado, and was told the whole time that I would have no future in that. Nobody ever gets a job if they study English literature. Where are you going to wait tables? That kind of thing is all I heard the whole four years I was studying it.

And the whole time I was thinking this seemed like a very good career move to me, because it seemed like communication would be good in any field. So I was really happy when I was offered a job at IBM. It wasn't the type of writing I was expecting to do, but it was a really interesting type of writing.

It was tech writing that Michael and I did. I just found it really fun to take these tricks that I had picked up in creative writing, and these turns of phrase and style that I had tried to develop in college while reading the masters and while participating in discussion groups and such, and then taking that creative approach to writing and pointing it toward IBM manuals. I was really fascinated with how much room we had to work with that. You had to make clear, logical, obvious points about the software and tools we were writing about, but it could be done in a less dry way than was traditional in those days.

These days I think people are used to seeing more style in tech writing with online manuals and Google help systems and Apple online help and that kind of thing. But we were writing about mainframe software for engineers, it was pretty bereft of anything that wasn't just the dry facts. I thought it was really educational to look at this cloud of engineering gobbledygook and try to translate that down into something that was not only easy to understand but also enjoyable to read. And in the process of doing that with Michael and other really good people at the Santa Teresa Laboratory, now known as the Silicon Valley Laboratory, I realized that same skill set would work with other fields. I'd always been interested in finance, and it seemed equally arcane—right up there with computer technology, if not more mysterious because of all the conflicting interests and crosscurrents. So I decided to take that skill set to the world of finance and really never looked back.

The first title I wrote was just for friends and family as a Christmas present. That's why I called it The Neatest Little Guide to Mutual Fund Investing . I didn't really think it would go anywhere, but people made photocopies and photocopies and photocopies of it, and finally somebody said, "You know, books can be published." I thought, "Hmm. That's true." So I started looking for an agent and as luck would have it, there was a brand new agent starting out in New York City at that time, called Doris S. Michaels. I was a brand new author and she was a brand new agent. She wasn't even listed anywhere. One of the many rejections I received came with the kindness of a margin note. "I make no representations for Doris Michaels, but she's just starting out and might take a look at your work." Turns out Doris' husband was the European equities director for Goldman Sachs, and it seemed like a perfect fit. She signed up the title and it ended up being published by Plume, and turned into a series that just won't quit. It was one of those lightning strikes that made all the difference in my life. . I didn't really think it would go anywhere, but people made photocopies and photocopies and photocopies of it, and finally somebody said, "You know, books can be published." I thought, "Hmm. That's true." So I started looking for an agent and as luck would have it, there was a brand new agent starting out in New York City at that time, called Doris S. Michaels. I was a brand new author and she was a brand new agent. She wasn't even listed anywhere. One of the many rejections I received came with the kindness of a margin note. "I make no representations for Doris Michaels, but she's just starting out and might take a look at your work." Turns out Doris' husband was the European equities director for Goldman Sachs, and it seemed like a perfect fit. She signed up the title and it ended up being published by Plume, and turned into a series that just won't quit. It was one of those lightning strikes that made all the difference in my life.

Michael: How many of those are there now?

Jason: There are five Neatest Little Guide titles , and far and away, , and far and away,

the best seller is The Neatest Little Guide to Stock Market Investing

the best seller is The Neatest Little Guide to Stock Market Investing , which comes out with a new edition every two or three years. , which comes out with a new edition every two or three years.

Guy: And I see that you are rated in the top 60% with your estimates.

Jason: Thank you. [Laughter]

Guy: That's good.

Jason: Thank you, that's also been a good thing. I'll give you a little hint on that since we are speaking honestly off Wall Street at the moment. The key to achieving good forecasts is speaking less frequently than others. [pause, then laughter]

Guy: Now wait a minute. Clarify that please.

Jason: People that have to go on radio or tv weekly, or daily even, like in the case of CNBC, they're wrong something like 80% of the time in general. And that's because nobody knows day to day. But the way I've made my forecasts is by waiting for really big inflections in the market and then saying, you know, when the market has gone down this far, like we saw in 2008, it's going to go up. That's why my odds have been so much better than most—top 5%. But I do think there's a lesson in all that. Anybody who's a part time investor can do much better if they step back from the fray, rather than stepping into the fray.

Guy: Years ago, there was this fellow—you mentioned television—and trying to familiarize myself with the stock market, I started watching him: Rukeyser.

Jason: Sure. Yeah.

Guy: Well, it didn't work for me. So there it is.

Jason: There's an old saying in the business. "The brokers have nice yachts, and the stock dealers have nice yachts, but where are the customers' yachts?" Somehow those never work out.

Michael: Jason, I'd like to step back a step even farther, maybe before I met you. Tell us a little about your background.

Jason: Sure. I grew up in the Rocky Mountains, in Colorado, 20 miles from the nearest town. And the nearest town only had a population of 5,000 in the winter. That was Estes Park, Colorado. So I grew up spending a lot of time alone, hiking and horseback riding and swimming in rivers with dogs and climbing trees and that kind of thing. I didn't even participate in typical school sports that much. Instead I was doing things like rodeo and horseback riding and river rafting, that kind of sporting activity. So I was really from the countryside. But one thing our school had was this unbelievable speech and debate team. It's hard to explain. Nobody's ever been able to explain. Local newspapers did stories on it. Why is there this little fountain of intellectual activity in the middle of those mountains? Our school would routinely go up against schools from Denver, such as the behemoth in those days, Cherry Creek High School. They had hundreds of people on their team and we had four. And we beat them in the state championship. So yeah, there was something really nice about the combination of—I think in a way, that's a microcosm of my life later, which was to step away from the fray. There was something about being in those mountains with few people, looking over a limited set of information on the big issues of the day that really clarified thinking and sharpened wit, and produced these dynamite intellectual kids that came out of those mountains and down to the tournaments in the cities. It was so moving to see those kids in action. I grew up with those kids and I think it really set me on a course to a life of ideas and discourse and wanting to communicate and live differently than most people live.

Peggy: And did you write much back then?

Jason: I did. I wrote a lot. And I credit that not so much with school but with nearly dying from cancer when I was twelve years old. I had a malignant ependymoma which is a tumor in the spinal column. And I had to have microsurgery and chemo and radiation and the whole nine yards. It hung like a plague over my high school years. It was from junior high through the end of high school that I had to go in for regular checkups. They were always painful, of the spinal tap-myelogram variety, and when I first came out of the hospital I was given a blank diary by a man who had survived the disease, and was a member of our church. And he wrote in there that the great men in history took time to write down their thoughts, and that's why we think of them as being great. So why don't you write something down? That's what he wrote in the opening to that. He started me off in journaling, in those days we just called it keeping a diary. But it was a great kick start. I still have those, and it's fun to look back. That first one, covered in corduroy.

Michael: I don't think I'd ever heard that story.

Jason: Probably not. So even looking back on just daily kind of stuff, when I was a kid, and thinking about it got me in the mode of looking at what was happening around me, figuring out how to translate that into words, and then playing with those words. I didn't know that I was practicing for something to do later on. But now looking back, I think that was really important to me.

Michael: How many kids were in your family?

Jason: I'm the oldest of seven.

Guy: That's a sizable family. Do you get together very often still?

Jason: Yeah. Even though I live in Japan, I get back to Colorado two, sometimes three times a year, and I always stay for a month or so. My schedule is flexible and I can work from anywhere, so I take advantage of that to spend time with my family as much as I can.

Guy: You get along with your siblings then, it sounds like.

Jason: Yeah, we've worked through a few things over the years, and I do get along with them. Probably the sibling who is closest to me is my sister, Emily, who is five years younger than I am, and the next in the lineup. She and I are business partners at Red Frog Coffee in Longmont, Colorado. She's the talent and I'm the money.

Michael: Peggy has a Red Frog Coffee mug in her hand right now.

Jason: A true believer!

Peggy: That's right!

Guy: I just finished a book titled The Sibling Effect about how bonding occurs in sibling situations. One of those bondings it says, is that those kids who become adversarial younger, tend to bond better in later years. about how bonding occurs in sibling situations. One of those bondings it says, is that those kids who become adversarial younger, tend to bond better in later years.

Jason: Is that right? Well that explains a lot in my brief history with my siblings. [Laughter] We progressed from the usual fights around the dinner table, which, it's kind of funny that when you look back through the lens of time, stressful situations somehow become charming and endearing in retrospect, but when you really think carefully and talk to people, you realize they weren't charming or fun at all at the time. Later you think back and remember those times staying up late and somebody getting ticked off and throwing the game board across the room, and that kind of stuff.

And now it's like, "Oh those fun times growing up," but at the time, there were some pretty intense feelings.

And now it's like, "Oh those fun times growing up," but at the time, there were some pretty intense feelings.

Peggy: Michael used to tell me about times when the two of you worked at IBM and you would walk around the par course there on the Santa Teresa campus, and you'd talk about ways to get out of the corporate life. Life beyond IBM.

Jason: Yeah. You know how good I felt to find Michael there, because as I explained, I went straight to IBM from the University of Colorado, which was just down the mountain from where I grew up. So to make the trip out to California, and the heart of Silicon Valley, and to find a buddy who would take long walks through the hills with me was a real treat.

Michael: I was on a mission. My goal on those walks was to enlighten you about how the corporate world works, and to make sure you didn't get caught up in it too deeply.

Jason: You did a good job with that, and there was another...

Michael: You left before I did.

Jason: That's true. Another key figure at IBM that helped me realize that the corporate world was not for me, and that was my first editor there, Fred Bethke. Do you remember him, Michael?

Michael: Yes.

Jason: Fred was a great guy. A real intellectual. He had a PhD in—was it linguistics, might have been something else. Philosophy? If not philosophy, it should have been, given the type of personality he had. And Fred's the first one who indicated to me how things worked. I was talking to him about the new promotion plans; there seemed to be a new compensation and promotion and review system that would come out every quarter at IBM. And I remember saying to Fred, "Well. I've looked over the new system, and it looks like my prospect of promotion is pretty good, and it looks like if I do this and that, I should be up to this level in this amount of time," and he sat quietly and listened to all that. Then he said, "Look, I'll give you a quick shortcut. If you want to know where you'll be in five years, or ten years, just look where somebody else who has been here five years, or ten years longer than you is, and that's where you're going to be."

I thought, "Wow, I've got to get out of here." [Laughter]

Guy: In other words, there's nothing to merit.

Jason: Exactly. I thought, "I just cannot live in that kind of stifling predictability." So between talking to Fred and talking to Michael, and working on my own writing—and I realized something else too. When you look at business one of the things you realize early on is that business just comes down to selling something for more than it costs you to make it, whether that's a service or a creativity or a product. That's the basic formula for a business. Just look at your margin. And I realized, in order for IBM, or any employer to make money off of my talent, they need to pay me less than I'm worth. Otherwise, the business doesn't work anymore. So almost by definition, an employee is agreeing to undersell themselves. That didn't sit well with me at all. Underselling myself, combined with the predictability of being where that guy is five years ahead of me, or that guy ten years ahead of me, and the classic just wanting a better chair along the way, really kept me up at night. I just wanted to find a way to get out of there.

When I did finally get out of there, I left in four years, it wasn't with anger. I met great people, Michael among them, here we are still in touch. And IBM really did give me a break. I had student debt coming out of school, and the last thing I wanted to do was sit around growing a goatee and wearing a beret and calling myself a writer while sinking in poverty somewhere. So it was really great to get that break and work at one of the big corporations and to learn why it's not for me. But I've met a lot of people for whom it does work. So I still look back at IBM in a spirit of gratitude, and not arrogance or something, that I was able to escape the machine.

Michael: That's a good point. I also don't want to sound like we're trashing the corporation.

Jason: Right. I'll tell you something else. When you're graduating from school, you go to the employment center, and send out your resume, and nobody has much to say on a resume at that point. So you try to gussie it up as much as you can, and put your best foot forward. And everybody around me, all the people with engineering degrees and math degrees, physics degrees—those people were just gathering job offers and everybody was talking over lunch about "gosh, how am I going to choose? How am I going to choose?"

Well, I had nothing but rejections. I had this stack of rejections, and not one positive offer. It was getting pretty late in Spring, and I was starting to come up with plans, not just B, but C, D, E and F. And then suddenly, an offer came in from IBM. It said why don't you fly to either Florida or California and interview with us and we'll see if this can work out. That was my one single job offer, so it was a pretty simple decision tree for me. I got one chance, and that chance came from Big Blue.

Guy: Big Blue. I've never heard that phrase for IBM.

Michael: Oh, that's a standard nickname for IBM. Big Blue.

There's one other little tidbit, I guess it's an anecdote, from those days when we walked the par course. What we were doing those days, was picking our brains and trying to figure out how we could make a lot of money through the internet. This was what—mid-90s? I'm not sure when you started.

Jason: I started IBM in 93, so these were the early days of Netscape even, that we were talking about how to make money online.

Michael: Yeah, so this was the mid 90s when this was happening, and the internet was a very different creature than it is now. But we still could see that there was a lot of potential there. So every day, we would take these long walks and talk back and forth. There's got to be something. We could do this. We could do that.

And then one day you came back from the weekend, and you were guiding river rafting on the weekends at that time, and you said there was this guy in the boat, and he was talking about how he was making all this money every week on the internet. And I said, "Well, what's he doing?" And you said, "He's got an S&M catalog. He sells—you know, leather. Whips and chains and bondage stuff." And I thought, "Well, that's great." But you said, "Well, I don't really want to do that, but I'm just curious what the system is that he's got going." Well, of course we know now, because a lot of water's gone under the bridge and we know that the particular industry he was in was huge, but we were curious about the mechanism. We were curious about the internet piece of it. So we slipped off for a long lunch one day that week. You made an appointment with him, and we drove from south San Jose up to San Francisco to talk to the guy. It turned out not to pan out and give us any good information, but I always remember that story and chuckle about it, because it was sort of typical of the openness we had at that point to try anything. We never set up our own sex shop but...

Jason: Thank you for clarifying that. [Laughter]

Guy: Although you'd be rich today.

Michael: We'd all be retired by now.

Jason: But you know, I think that a bigger theme from that, is that we learn things in the strangest ways in life. If people really keep open to things—I mean, right, we weren't interested in an S&M shop or anything to do with the adult industry on line, but that guy running that shop had servers and a photography studio, and he figured out how to do e-commerce, and he was looking at how to reach people, and granted, the thing he was selling was not up our alley at all, but the way he was doing it was actually very helpful to know. Take a few notes and see how one sets up a store on line in those days.

I think that also has been a thread throughout my life. I learn so much more about financial markets, business success, marketing, by talking to people in offbeat venues than I do in boardrooms and seminars. I think it's a real testament to the idea of keeping your eyes and ears open at all times.

Guy: One of the things I became curious about, and now that you have brought the corporate world into the discussion, perhaps it's appropriate to ask this question. In your success with your books and then with Socks for Japan, you had to set up a full organization to be able to handle everything that you were doing. Now as part of that, do you find yourself back into the corporate world with others working under your direction, or have you been able to set up an entirely different system than the corporate standard?

Jason: I've set things up very differently. I used to think the way to measure success was by the number of accountants and consultants involved in setting things up, and now I look at it almost the opposite way. What can I do with the fewest dependencies?

For example, with Socks for Japan, that was a big organization, so we did have a structure with that. We had somebody in charge of the warehouse, we had somebody in charge of the web site, we had to divide up duties. But it was all volunteer, which was a whole different kettle of fish. People even talked about this late at night when we were sorting socks and getting ready for the next run into the disaster zone. People would say, "Wow, this feels so different than work." You know, almost everybody who volunteered had a regular job. Nobody cared about promotions, or who was getting paid what, or look how much time that guy's spending with the boss—there was none of that going on, because it was really in the spirit of "We've got to help these people."

You remember the urgency following March 11 last year. That atmosphere is not one you encounter very often. So the organization was completely different from what you would find in a corporation.

You remember the urgency following March 11 last year. That atmosphere is not one you encounter very often. So the organization was completely different from what you would find in a corporation.

Michael: Back up for just a second and give us the framework of what happened with Socks for Japan. How it got started and why.

Jason: Sure. It was a Friday, March 11, and I was working as usual in my office. Earthquakes happen all the time in Japan. Frequently it's two or three times a week. So shaking around is just no big deal at all. And I actually have never been bothered by earthquakes at all. They don't bother me a bit. This one was different, and you knew it was going to be different even ahead of time. Have you ever been in the mountains and there's a wind coming, and you could hear that wind come over the mountains in the distance, and come down the side and through the trees and you can hear that wind approaching you?

Michael: yes.

Jason: Imagine that same idea, but instead of wind, it's a roar in the Earth coming from far away toward you. It was really creepy, and somewhere deep inside my genetic history, I understood that this was a big deal and not good. The hair stood up on my neck and everything, just from that sound in the distance. I didn't know what it was—a bomb coming out of the air, who knew. Then things started shaking, and I guessed it was a massive earthquake. I jumped up and started catching things and closing things and just trying to salvage things and get myself to a safe place. I tell you what. That was not shaking when that thing hit. I have this large window in my office, and it was open, and I could see out to the neighborhood and the buildings beyond, and it looked like the whole area of buildings, the distant park, was surfing on dirt. The whole thing just turned to waves, like the ocean or something, and it was just incredible. But nothing shook down. It's amazing what can get through that. So that's how March 11 happened to me, and the power was out, the phones were down, so nobody knew what was going on.

Peggy: Jason, you were located how far from the earthquake.

Jason: This was a hundred miles away from the epicenter. Farther than that, the epicenter was out at sea. But the heart of the disaster zone was 100 to 200 miles away. There was quite a range up there. So I wasn't anywhere near where it hit hardest. And still it was that big here, so—well, it was the largest earthquake recorded in Japanese history, and Japan is known for earthquakes, so that says it all.

Overnight, we didn't know what was going on. People were just trying to get through that night. And then the next day, when the power came up, and the lights came on and the news came on, there was just this silence over the whole land as everybody looked at what had happened up north. So that was Saturday. I had to work on my letter, but it was hard to focus on anything beyond this.

It was the next day, Sunday, that I went over to the public area, and I expected to see people organizing volunteer efforts, and talking about who they knew as relatives. It was a shopping center, which is sort of the center of town here, so it was a good place to go to see people. I was shocked at the lack of shock. That's a good way to put it. I couldn't believe it when I got there and there were no vans, no announcements, no sign-up areas, no cordoned off lines of people waiting to figure out what they needed to do to help. No. It was people getting movie tickets, and checking out the latest Louis Vuitton bags, and complaining that there was such a long wait to get into the restaurant, and I was nauseated, to tell you the truth.

I couldn't believe it. I thought I've got to get out of here, first of all. I've got to do something. I thought I could sign up somewhere, but there was nowhere to sign up! I thought, "I've got to create somewhere to sign up." So this core group of people, we just kicked it off.

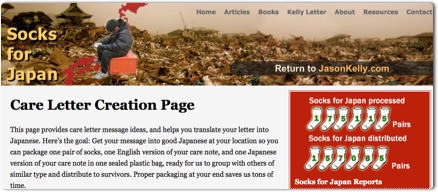

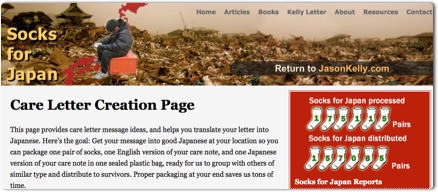

We made the website that night using a subsection of my own site. We figured Socks for Japan was what we could do. We researched very quickly what would work. Contrary to what critics said, we approached this very responsibly, knowing that most citizen efforts to help in a disaster result in this flea market scene of a bunch of piles of odds and ends that people don't need—just this random collection of whatever junk people happen to have in the garage. We knew that wasn't needed.

We made the website that night using a subsection of my own site. We figured Socks for Japan was what we could do. We researched very quickly what would work. Contrary to what critics said, we approached this very responsibly, knowing that most citizen efforts to help in a disaster result in this flea market scene of a bunch of piles of odds and ends that people don't need—just this random collection of whatever junk people happen to have in the garage. We knew that wasn't needed.

People were already saying on TV news, "We need socks. We need socks and underwear." That's what people said a lot. We figured "Socks for Japan" was easier to pull off than "Panties for Japan," so that was our focus. [laughter]

People were already saying on TV news, "We need socks. We need socks and underwear." That's what people said a lot. We figured "Socks for Japan" was easier to pull off than "Panties for Japan," so that was our focus. [laughter]

You know, socks have a lot of benefits. They're cheap, they're available everywhere, everybody needs them, especially when people ran away barefoot. It was cold then, it was snowing in the disaster zone, they don't go bad, they don't break, they don't spoil, so it was really a perfect focus.

Socks plus care letters to boost people's spirits in a sealed bag. That became our formula. A place to send them, right to my office, and we coordinated with the local delivery people to take it out to the warehouse that we were able to borrow for free from an accounting firm.

And also, we double checked with all the delivery services to make sure we weren't going to be overwhelming the infrastructure during the relief effort. Everybody said no. So we were very careful to start things up right, and to not burden the system and cause more trouble, and deliver things that were not needed. Nope. We had perfectly sorted, 100 pairs per bag, men, women, boys, girls, babies, sealed, ready to go. And I tell you, city leaders were calling us saying we've got 600 people in a shelter here. And we could say, "How many men? How many women? We'll be there." We were making up schedules just like that, so I'm very proud of what happened.

I know, Guy, your question was what was it like to run this organization, but the urgency of the moment ran it for us. There's a feeling in Japan—comparing America and Japan, we often say about America that there are often too many chiefs and not enough Indians, that everybody is competing to be the leader and to be the boss. In Japan, there are frequently too many Indians and not a chief in sight. So to combine this American idea of we've got to do something, this is what needs to be done, give me the people to do it, boy, those people show up. It was a fantastic combination.

At least with our volunteers, but I think you could pull this off in other places in Japan. You could say to somebody, "Alright, we've got 2000 pairs of socks here that we need to sort tonight. We need people here to do it tonight." It gets done tonight. There was just this fabulous efficiency and dedication to it. There were no hard feelings, none of the usual things you hear people complain about in a corporation. But I think that's not because of the way we set it up, but because of the circumstances that caused us to set it up.

At least with our volunteers, but I think you could pull this off in other places in Japan. You could say to somebody, "Alright, we've got 2000 pairs of socks here that we need to sort tonight. We need people here to do it tonight." It gets done tonight. There was just this fabulous efficiency and dedication to it. There were no hard feelings, none of the usual things you hear people complain about in a corporation. But I think that's not because of the way we set it up, but because of the circumstances that caused us to set it up.

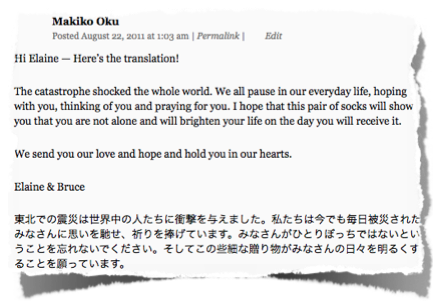

Peggy: Jason, talk about the personal notes that were a part of the packages of socks.

Jason: Our package was very carefully arrived at. On the one hand, people really did need a good. On the other hand, people needed their spirits boosted. There were other groups that were handing out just letters. I think that was nice for people to get. But there's something about the way we give a gift at holiday time or birthdays, where we get a gift plus a card. It's nice, and maybe you've noticed in your history—I've noticed in my personal history, if I give somebody just a gift, They will say thanks, but sometimes they will even say, "No card?" And if I give somebody just a card, they're usually happy just to get the card. But it seems like the best combination is a gift plus the card. I care about you, I love you, depending on the event, and then here's a gift.

So you have a tangible proof and you have this emotional proof too. It's just a great tried and true combination. And what happened after this disaster happens after every disaster, which is why we could research this and forecast how things would go for the survivors. Very quickly, they have a roof over their head, they have a mat on the floor, they have ramen and something to drink. And once those are supplied, the shelter, the food, and the clothing, then there they sit. Three members of the family dead, house gone, company wiped out, all hope of a future gone, but they're checked off as having been supported. So very quickly, the greatest need is psychological and emotional.

You've got tens of thousands of people sitting in these converted gymnasiums and other public spaces, separated from each other by cardboard, with total strangers, mourning the loss of their life entirely. It seemed like fairly quickly, what they would need is comfort. The equvalent of comfort food. We're not in the food business, but we could provide for their feet and care for their heart, and that's why the package became that.

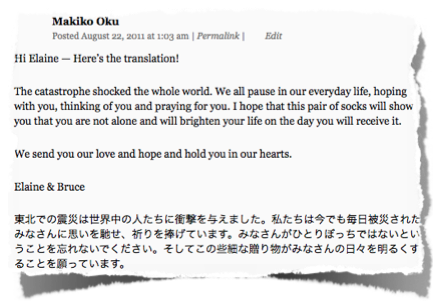

The letters became really important. One thing we had to do was to bridge the language barrier, so we set up a simple system using the comment structure on my website. Somebody would type in their English and and then we had bilingual people who would look over them and reply to the comment right there and show how it would look in Japanese. That way other people could pick out common phrases and get their letters in Japanese that they could enclose with their hand written English version.

Michael: And you had donations coming in with these notes from where?

Jason: All over the world, but far and away, our biggest supporter was the United States. It is a very generous country. You hear that a lot. It was very moving to see the efforts at churches and cub scout troops and brownie groups and neighborhood drives all over the United States. It was really nice for me too. The whole world felt turned upside down, and to receive packages from America and the way people write, and common phrases that you [in Japan.] Even bilingual people here speak as if they're speaking from a textbook example, because that's how they learned their English. So to get native English from back home was really good for me. But it came from all over the world. I think a little more than 70% was from the U.S. though.

Peggy: Did you ever figure out what the malaise—the reaction from your town, where there were no places to volunteer, there were no outlets to help people—did you ever figure out what that was?

Jason: I've got to be honest. These kinds of volunteer efforts are not entirely the up music, Hollywood ideal that's presented so often. Whenever somebody does a story on one of them, it's always the good moments, the happy moments, the helping moments, but there's an awful moment where you think, "What the hell are we bothering with this for?" You know, these people we are trying to help don't even seem to care. That wasn't always the case, but it's not like this Disney scene where you show up to nothing but open arms all around and everybody just can't wait to see you. I remember some of the classic moments where we were handing out socks and comforting people and most of them were grateful, and then somebody would say, "Don't you have any red?"

Peggy: So recap, how many pairs of socks did you distribute, in what period of time?

Jason: We distributed 160,000 pairs from one week after, so from about March 18 to early July. We actually went to the first anniversary, but most of our distribution happened in that first four months.

Michael: Ok.

Jason: But the point I was making is that it's not all fun volunteering. It's not a lot of Hollywood feel good moments at all. It's a lot of hard work, but the hardest part is that the survivors, the people you want to help, are not always happy to be helped as you thought they would be. It hurt a lot of our volunteers' feelings. That was the hardest thing to get used to. It's not the long hours or the hard work without pay. It's the lack of gratitude sometimes.

So you were asking, Peggy, why the indifference in Sano. I actually think that was a big part of it. There's a bit of a feeling in Japan, that if it didn't happen to you directly it's not your problem. You watch it on the news, you could say, "Wow, that's too bad. I don't live there."

I remember very many discussions in our long van trips where people would be talking about this. We usually took four people on these long days. And I remember a couple of discussions in the van where people would say, "You know what? All these people that we complain about in Sano, the guys driving around in their cool cars trying to get gasoline that's being rationed so they can drive around some more, or people that otherwise aren't pitching in to help at all—do you realize that if the tsunami had struck Sano, the people we are going to help right now would not be going down to Sano to help?"

It's the same group of people. This group happened to be hit by the tsunami, that group didn't. That was really challenging for a lot of our volunteers, and I felt it many times too. I'll tell you one anecdote.

This was, I think the saddest moment in the whole trip. And it wasn't a victim that was sad, it was one of our volunteers. We pulled up near Sendai, and we were deep in a neighborhood area there. We'd gone to several big shelters, and it was right along the coastline. At that point we had been doing it for several weeks, so people had plenty of stuff. And we got to this one shelter, and they were really taken care of. They didn't have a lot of socks though, and that was part of our plan. Socks and underwear are always forgotten. People get pants and shirts and jackets but they don't get socks and underwear.

So we showed up with the right stuff. But boy, the attitude in that shelter, I'll never forget. We came in and went up front and made an announcement. It was mostly these older ladies that were there, and they just looked really impatient, like "Come on, get on with it. What have you got? What have you got?" That was the feeling. So finally we set up to distribute the socks and people lined up. We would give them the two or three pairs per person that we had as the quota.

One of our volunteers, Rumiko, gave this pair of socks that was really beautiful from somewhere in the United States, and they had a hand written, hand cut out note—it was beautiful stationery that somebody had made for this, and wrote in really touching language about how much they cared, and what was special about these handmade socks. So Rumiko explained that in Japanese, to the woman, gave them to her, and she just said, "Fine, fine, fine" and as she walked away, she reached into the bag, took out the note, threw it in the air over her shoulder, and then dropped the plastic bag on the floor and took the socks back to her place.

I could feel how crushed Rumiko was. And she stood up from the distribution line, and walked over and picked up the discarded care note, and blew it off, and tapped the dirt off of it, and she placed it carefully in that plastic bag, and sealed it up, and as she turned around to come back, I could see that her eyes were red. She put that in her pocket and she kept it to this day. And I remember her saying on the drive back, "I often feel like our clients are the donors, not the survivors, and I never felt that more than today." So there's a little peek behind the scenes at Socks for Japan.

Volunteer Rumiko taking a moment by herself during

a difficult Socks for Japan distribution day.

Michael: That's an interesting story.

Peggy: You also had amazing photos and you wrote these incredible stories about the people you encountered, and the devastation in these little towns. I know I've pointed a lot of people to your website because I think it was documentation we weren't getting.

Jason: That's right.

Peggy: We never saw it in the media here in this country.

Jason: Oh gosh. I tell you, Peggy, I have never understood better the disconnect between the news and reality. So many times we would be in our van in the middle of a place that had just made the news somewhere, trying to figure out where the heck they got the story they just reported. I mean it was amazing the disconnect. All I can come up with is that the news chooses the story they want to tell, and then they go out and find the evidence to prove that story. Who cares if when they get out there, the evidence they find is only five percent of reality. Going with that preconceived narrative is all I can figure.

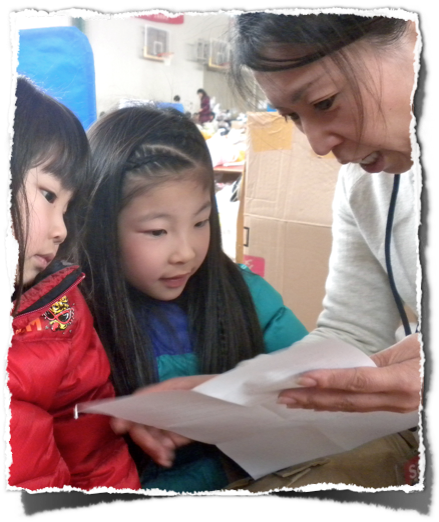

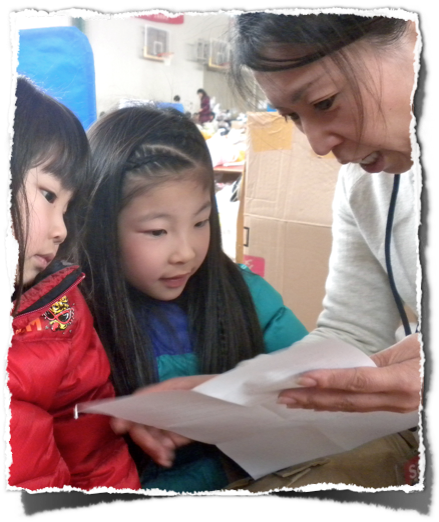

But I want to come back to something you said that ties in with what Guy said earlier about the organization. Our effort was so successful because of the research done by my girlfriend, Takako Otani, [in the photo to the right, reading a care letter to survivors in a gymnasium shelter] who doesn't live in Sano. She's bilingual, and she would research from her home office in Kumamoto, which is hundreds of miles away. It's on the southernmost island. She would call the disaster towns and she would come up with a detailed plan each time. She would handle all of that by herself so that we could be processing all the deliveries coming in. And she also went on many distributions too. But because of her, we were able to find the places that really had the greatest need. Not necessarily headline places, but places where she had talked to shelter managers and city managers, and even people in the shelters, so that we had a list of mobile phone numbers that were working as we drove up there, and she had maps that were done out to show stop one and stop two, and she would even give directions from stop one to stop two. So I just feel like no discussion of the efficiency of our effort would be complete without mentioning her. She was absolutely critical to this. Honestly, I don't think we could have done this without her.

I guess I'm still on the organization theme. I think this is one of those cases where it's like something out of a Malcolm Gladwell book, where you can take this giant network of people, but frankly, it comes down to two or three or four that really pull it off, and everybody else is in a support role. That was definitely our situation. Without Takako running research we'd have had nowhere to go, without Rumiko running the warehouse, we'd have had no organization with our inventory. The power of a few people is very clear to me.

Guy: Something you say too rings a bell with my own experience. Having had corporate background similar to yours, and then ending up working for years with a non-profit mostly volunteer organization that was efficient, well established, and ran like a smooth top. It was primarily volunteerism.

Jason: Yeah, there's really something about everybody being in it for a common purpose rather than just trying to get money or something else out of it. There's something about volunteerism, exactly as you say, Guy. It makes for a very well run operation.

Guy: Somebody has to do a study on that to find out what is it about the volunteerism side that increases productivity.

Jason: I suppose it's just that there's no sense that everybody is competing against each other. There's no sense that, "Well, I can process more socks than that guy, why is he getting paid more than I am?" You don't have any of that stuff going on.

Guy: Yeah.

Jason: It almost seems like everybody is so proud of everybody else for showing up that there's this real communal support that arises.

Peggy: And people are there because they want to be there.

Jason: Yeah, that helps a lot.

Peggy: Which touches on something I picked up on from your book. I guess that's your most recent book, Financially Stupid People Are Everywhere: Don't Be One Of Them . That is the whole notion about financial freedom, and getting people on the right path so they can have a choice of taking the job they really want, or walking away from a job they don't want and being able to do something they're passionate about. . That is the whole notion about financial freedom, and getting people on the right path so they can have a choice of taking the job they really want, or walking away from a job they don't want and being able to do something they're passionate about.

Jason: That was a theme in my life after I left IBM. I didn't ever want to work at a job again. And the main balance everybody has to strike is how much time should I put into work to make money in order to have the freedom to do things I want. It seems like we always have one extreme or the other. We have plenty of money but no time, or plenty of time but no money, and trying to walk that balance beam is the whole trick.

But Michael mentioned earlier that we always saw the internet as having great potential here. It's never stopped fascinating me just how much financial freedom the internet can create. It's available anywhere on Earth now, so if your business is online, you can really go anywhere on Earth. You can work on a vacation, although it's better not to work on vacation, but you can certainly live wherever you want. That was the key for me.

I knew that I wanted to do a type of writing that doesn't pay very much, and that's fiction. I've always wanted to write fiction. I've only had one successful novel. Even that was tied to a non-fiction event: Y2K. It did very well ahead of the year 2000 computer problem, that ended up not being such a problem. But in 1998 and 99 there was an awful lot of attention on that issue that really helped my book along. My book was a novel about what would happen if the whole world went dark and shut down.

But beyond that, I haven't been able to make any meaningful money in fiction. And personally, I like my fiction. But the market doesn't seem to like it. I realized early on that this could go on for a lifetime. Just look at the history of great writers.

Michael: Well, one thing about that book that you haven't mentioned is that you self-published it. And we saw the work you put into the promotion of that book. You didn't just hand it off to a publisher and wait for them to do something with it. You were busy. You were very busy when you were promoting that book.

Jason: Yeah, that's a good point. It didn't happen easily. I remember several publishers coming back with these cockamamie ideas like, "We'll be sure to get that out in the summer of 2000."

Guy: Jason, while we are on this, you should give out the title of that book.

Jason: Y2K—It's Already Too Late

Guy: OK, and that's still available on Amazon?

Jason: Sure!

Michael: It definitely was a fun book.

Jason: You're right though, Michael. It did take an awful lot of promotion. I ended up realizing that New York, meaning the publishing industry, couldn't get that out in time. So that was my first foray, and last I will point out, into physical self publishing.

Guy: It's a lot harder because then you have to be your own promotion, marketing, and public relations person.

Michael: And warehouse.

Jason: Exactly. The biggest business challenge was inventory management, because the more books you print, the cheaper they are per book, but if you print too many of them you've got a garage full of books forever.

It's just an awful industry. I for one am very glad that that industry has been so disrupted by new technologies. This is how awful it was. And remember, this is not ancient history. This was 1998. At that time, you designed the book in software. You had a file. That file went off to a printer. The printer set it up on an actual printing press, and rolled off a quantity of books, and I paid the printing press. I'd pay them, and they'd be delivered to me, and then I'd have to get them out to distributors who got them out to book stores. Some people remember book stores?

Guy: Oh yes. I think I do.

Jason: A bit of history there too. Barnes and Noble and Borders and independent book stores receive their books from distribution warehouses run by Baker and Taylor and Ingram. So I had to have accounts set up with them, and here's where you'll see how hard it was. I had to pay to ship the books that I had paid to print, ship them to warehouses at Ingram and Baker and Taylor. They then took over distributing them out to bookstores on demand. The bookstores would display the books. At the end of a certain amount of time they would return whatever books had not sold, in whatever condition they were in, marked up, torn, however they had been beaten up in the store— back to Ingram or Baker and Taylor, who would eventually ship them back to me, and I would have to pay return freight as well.

So it wasn't just me, that's how the book business worked in those days.

It was just awful! Look at all the headwinds in that. So when you've been through that, and then you catch up with print on demand, and e-books, things have become much, much easier these days. [pause]

So, what were we talking about?

Peggy: Financial freedom. I must confess that when you first told us about your book, Financially Stupid People, I read the little synopsis, and I thought, huh! I'm obviously one of the stupid people. I'm one of the morons. I'm one of the deadbeats. I mean we sold the house on a short sale one year ago. I thought it was like going to the dentist. I didn't want to read it.

But I read it this week, finally, and it's a wonderful book. It's a book that everybody should read. It's a book that I'm going to make sure all four of our kids read. It's written so simply, so clearly, from a historical standpoint, from a business/corporate standpoint, you weave it all together and explain an incredible amount of information in a relatively short space. And you give people really concrete ways to get on the right track.

Jason: Well, thank you for that. I think it's the most important financial book I've written, actually. Because even though my stock book is far and away the best seller, I don't think most people need to be jumping straight to stocks. You wouldn't believe how many people are out there, 30, 40, 50 thousand dollars in debt, who are more concerned about where to put this two thousand dollars in their Ameritrade account than how to get out of this much bigger problem they're in. It's just amazing.

There's something about the gaminess, the challenge, the adrenaline of the stock market that just grabs people before they've figured out their much more important overall financial picture. But that book was special to me because, as you know since you read it, it very quickly goes beyond the basic rules of finance, which are not that complicated. I tried to present them in a really snappy, easy to understand way in the first few chapters. And then I ask, if it's this easy, why in the world is so much of the country on the wrong track.

What I wanted to show in this book is that most people really are financially stupid, and they're just rummies that can easily be moved around by these corporate and political influences so that the whole goal, the whole machine of society, is just intended to transfer money from the poor and middle classes to the rich. Very quickly, the default paths in front of people lead them into getting into as much debt as quickly as possible, where they'll stay the rest of their lives. I mean that's a perfect citizen for government and business. Debt payments to corporations, permanent tax payments to government, and there you go. That system has nothing to do with personal freedom—these containers of money, future cash flow, that every citizen has tagged to their forehead that corporations and government divvy up.

I wanted people to see that in a non-partisan way. Both parties do this. At the time I wrote this book, Barack Obama was the new president, and there was still a lot of hope and desire for change behind his administration. The book pointed out before this became true, that you will not get any of the things you expect to get. Because all we have to do to understand what we will get from President Obama is look at who paid for his career. And guess what. It's the same people.

What I try to point out in this book is that neither party has your back. They're self-serving because they're funded by the same groups. This is our basic problem. And most recently, we had both conventions. Do you realize that the corporate backing for each convention was the same? You can follow the trails and see that both conventions were paid for by the same pools of money. It's just incredible how people keep falling for this circus of choice when there isn't a choice at all.

The point of this book is not to change that. In fact, I say at the end, it will never change. It will never get better! Bankers will never stop doing what they've been doing forever. It will always be this way, so we have to get smarter, and understand not to get in debt. Not to get tied to situations that remove our freedom, and certainly not to fall for another load of bull in an election campaign.

Guy: Are you familiar with Chris Hedges?

Jason: Sure.

Guy: Have you seen his new book, Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt ? ?

Jason: I haven't read it yet, but I know what you mean.

Guy: OK, because what you're saying is exactly what he says about our elections. He says that candidates are owned wholly by the corporations.

Jason: One thing I'm really proud of about Financially Stupid People is that it predicted before we knew the outcome of the Affordable Health Care Act, what everybody calls Obamacare, before we knew what that was going to become, this book predicted what it would become. Because all we had to do, and all we ever have to do, is look at who is paying for what. OK, we can see that the very best thing for people would be a single payer system. Now right there, part of the Republicans are ready to cut my head off, but we're just looking at this through a purely financial lens. The typical household—we pay a certain amount of taxes. Right now the only thing you get back from your taxes is wars and bank bailouts. Bombs and bailouts is what you get now. If there was a single payer healthcare system, at least you'd get something back from your tax payments that would help you.

Barring that, the next best thing would be, cut my taxes way, way down, and then send me into the free market to buy my own health care. Now the Democrats want my head.

The worst option, which is what we always get, is we continue paying high taxes, and we don't get a good healthcare system. And guess what. That's where it went. The insurance companies have a guaranteed customer base, and I know there are some improvements, and that's what the Democrats keep talking about, but we didn't get single payer and we didn't get a lower tax base, and a freer market system. No, instead, we got right in the middle, and are paying high taxes and are forced to buy insurance from private companies. It's just amazing. I was really proud, even though discouraged, that the book was able to foresee that outcome just by looking at the money trail.

Michael: I'd like to take us a little different direction now. It's something I want to be sure we cover, and that is your newsletter. Tell us a little about how you started it, why you started it, and how it works.

Jason: Sure. It has its roots when we were at IBM again. One of the things we were interested in was selling newsletter subscriptions on line, and I was trying to figure out how to step away from IBM. I wanted to step away when my income from outside IBM matched my income from IBM so I could have an easy transition. And income from my books was spotty, and remains spotty to this day, because you only get royalty payments twice a year. It's hard to live on two checks a year.

So I wanted a more steady income and I figured a subscription newsletter business would work. In those days, the only thing I could do was a print newsletter. There could have been an email list, but the web wasn't really going yet, and it wasn't really hot. People were still reading paper in those days. So I designed one that would go out in the mail and worked with the postal service to make it right. And I kept that going—it was called "The Neat-Sheet"—for years. It came out once a month and I took it from where I lived in San Jose down to Los Angeles, and continued producing it there, but realized when I wanted to move to Japan that I couldn't run a print newsletter very well from Japan. So I shut it down.

I moved to Japan, because it was really important to me to live in a very different culture, and it was one of the reasons I left the corporate world—I wanted to be able to go wherever I wanted. So once I was in Japan, I realized that I could run that newsletter electronically. And I reintroduced it with a whole new name, The Kelly Letter.

It started from Japan seven years ago, and one of the breakthroughs for me was not needing to get paid by check or even credit cards anymore. PayPal at that time set up for the first time, to my knowledge, set up this very easy subscription system where people could automatically pay every week or month or whatever I wanted to set up. But the point was automatic payments. That was just perfect for what I wanted to do. The introduction of that technology was what allowed me to start the newsletter from Japan. It's just grown since then. I use Amazon Payments now, but it's the same idea. It goes out by email every Sunday morning, and has just been a fantastic way for me to live wherever I want and make a good amount of money.

Michael: Our readers will recognize your basic model I think, because I have to admit, you know we've only been doing this for a year now, and in fact this interview will come out on the one year anniversary of when we started. And before we started, we picked your brain. We knew you had been doing this, we knew it was going well for you, and we decided we wanted to see what we could do. So we used you as a model. In fact, what we're doing is still very much along the same lines as the model that you use.

Jason: Yeah, it's a good model. It was really fun actually, talking to you about what you wanted to do, and it was interesting to see how this model works for a completely different editorial focus. I really like what you guys have done, by the way. The rich content. My newsletter remains plain text. I don't do any images or rich media at all, so it was neat to see you go another direction with it and use HTML with images and even multimedia. People can click to hear music that Guy Rathbun talks about, or a video that you found somewhere. You use the model I use but have taken it up several notches in the formatting.

Michael: Well I think the reason we needed to do that was because of the content that we have. It's a very different style and a different type of content than what you do. Yours is much more information dense...

Peggy: The audiences are different. I think your audience is probably used to the letter format. I remember my father used to get the Kiplinger Letter, so that's always been a part of the financial industry. So they're used to the narrative, as opposed to our audience, which started out with a lot of visual artists, and we are trying to expand that more generally to people who are following a creative path. Certainly our target audience is different so the format's different.

Jason: Yeah, that's true. It's a really, really nice product that you guys have created. I'm a happy subscriber and I've kept every issue.

Michael: Well thank you.

Jason: I don't know if there's more you'd like to know about the Kelly Letter business model.

Michael: If there's more you'd like to share, sure.

Jason: I recommend that if you are going to start a subscription information business, that you begin for free, just to get a critical mass of people so you're not writing in the dark. But fairly quickly, you assign a modest price to what you do. And make sure that your content is going to people who are paying.

One problem, in my opinion, with social networking and a lot of the free services that have arisen online is that people get sucked into giving away all of their talent. I am amazed at what people are giving away for free on line. I'm a grateful recipient of a lot of it, but as somebody running an information business, I learned early on that you cannot give away your best stuff. There's a lot of marketing value in scarcity.

If people understand, "No, you can't read what I'm writing for people Sunday morning unless you pay. The good news is it's not very much that you have to pay. So click here and come onboard. Get on the list." That's a very compelling situation for people, I think. And there's something about being told, "No, you can't come in." It's like the door to a club that's closed and a guy is standing in front of it. You can tell that something cool is happening inside, but you're not allowed to get in. Just buy a ticket and you can go on in.

That works a lot better than just counting followers on Twitter or likes on Facebook or that sort of thing. I strongly discourage people from giving away everything they do in the hope that out of the goodness of their hearts people will start to pay for what they have been getting for free.

The writer, or the producer of the material deserves more compensation. We can't eat from Twitter followers or Facebook likes or download counts. Those things are nice measures of progress, but in fact, I've found that in my business it's much better to get a lower volume of sincere, organic, loyal customers than a giant cloud of frenetic likes and positive words and praises but no income. In my business, I keep it real simple: how much money is it making? How much money is this customer worth?

That's the difference between volunteering and running a business. I think people confuse that online. No, time spent posting brownie photos on Facebook is not marketing, and people are calling it that. Maybe for some business models it can be. If somebody is trying to build a celebrity status, for whatever that does for their career, that might work. But in my business of selling information it does not work to give away great quantities of that information in the hopes that somebody will begin paying for it.

Michael: So this brings me to the next question, which is, how do you promote your newsletter? How do you market it?

Jason: The main marketing for my newsletter has been my stock book, because they're so closely integrated. So I really like that business model, because I'm paid when somebody buys the stock book. And it's a very good book, and it helps them get started in a responsible way with stocks, and then they are encouraged to sign up for my newsletter.

So I'm not spending money on marketing, I'm actually earning money through the most effective marketing method. Now, this is odd advice. Well, it's not advice, I'm just reporting on how I do it. But if somebody is taking this as advice, you have to back up much farther than write a book that tells people to sign up for a newsletter. You'll lose people in a hurry with that. If you're not giving something of value, people will really resent it.

What I have found, is just whenever I'm doing something public, I need to make people interested in me. Make people want to know what it is that I'm sending out to a select group of people every Sunday morning. And once they have that interest, that curiosity, Google makes finding me a snap. If they know my name, really that's all you need. If you put "stock" and my name in Google, I'll be the first one.

So really, Michael, my best campaign is, do really high quality work every time I do work, and make sure they know what my name is, and that will bring them to me.

Guy: I was going to say, don't just go by the name, because that's what I did, and I got a tattoo artist.

Jason: Yeah, he's number two. [laughing]

Guy: Yeah. From stocks to tattoos. I wondered what your tattoos were.

Jason: It's a funny collection of Jason Kellys. I'm the financial Jason Kelly, there's that tattoo artist I think in

Atlanta. We've emailed a few times and gotten a chuckle out of the cross traffic there. And then there's another one from years ago who was an adult film star, but at least he had an extra e in his name.

Guy: Great. Here we are back at the S&M.

Jason: Talk about a repeating theme in my life. So yeah, Guy. There are other Jason Kellys out there, but it's not too hard to find my stuff.

Michael: I've heard you talk on the radio a few times, either actually on the radio or mp3 files of radio talks you have done that were on the internet and I think one of the interesting things is, the people that listen to this will get a sense of the energetic quality that you have, but that really comes through, and I think that's one thing that's really good for you.

Jason: Maybe so. With all that speech and debate I used to do, which I just loved, and still do—I enjoy speaking in front of audiences, and for example, talking with you right now, I'm really comfortable with that. And I also try to keep my writing casual, so that somebody can look at a complex topic and understand what it means, and be proud of themselves for understanding what it means.

Michael: Is there something particular that you'd like to tell us about? Have you got anything new coming up?

Jason: There's always something coming up. There are a few things I've been working on. The 2013 edition of my stock book is coming out. That's always big for me when a new edition of that book comes out. So that's a big one. It will be out in December.

Beyond that, I'm very interested in how the e-book market is shaping up. I've been watching the effect of e-books, of the Kindle, and the Barnes and Noble Nook on the publishing business, and have noticed that there's no single place where people can go that pulls together all the resources they need as a writer to get going in that business.

So I've been wanting to pull that together into a new website and service at ewritersmarket.com that will show people the resources available for editing their book, for creating a cover and other design for it, for submitting it to the e-book stores, and for promoting it and achieving sales. I think that's a service that's badly needed, and I think it could be a good business as well.

Often writers want a place where they can interact with other writers on a specific business point. For example, is this a good editor? Is this a good cover designer? Is this promotion service worth it? And I'd like to have a place that's open where people could provide ratings as they do with books and other products on Amazon, and really comment and have a conversation back and forth. So that's another iron in the fire.

Michael: It sounds very good.

Jason: It's still in production though. Not a full blown website yet.

Michael: I was going to say, do you have the website now?

Jason: I have the website, but it's not functional yet.

I'm also having a lot of fun as the co-owner of Red Frog Coffee with my sister Emily. That's really been an experience. A very humbling experience I have to say. Because I thought, going in, that I had some really clever marketing ideas and techniques that hadn't been used before, and I discovered directly that in small business in America everything has been tried and there really aren't a lot of tricks left over. It's a tough field to stand out in.

Michael: Well, it is a nice little coffee shop though. We've been there, and thoroughly enjoyed it. And your sister is a delight.

Jason: Yeah, she is. You know, you sometimes read in business biographies that you should bet on people. Don't worry so much about the ideas. Bet on the people. That really has been my experience with Red Frog Coffee. She is wonderful.

Michael: I would agree. You have a lot more experience with her than I do, but I would agree.

Jason: Thank you.

Michael: There's one question we always ask and that is: What advice would you give to someone who is in the position you were in when you were in those latter days at IBM thinking about how to make your own lifestyle? What would you advise people to do, or not to do in trying to make that change?

Jason: I would advise avoiding rosy projections. The reason is that a lot of people, when they're working their job and have a steady paycheck, and then they have an idea for something else—it's easy to get excited for something else, and project results. If a hundred thousand people are looking at my web site, and only 10% of them get on this list that's ten thousand people, and if 10% of them do this...you can run those kinds of regression projections, and come up with, "I'll be making $15,000 a month in just two months after I quit my job, so I'm going to go for it." Somehow, it just never quite works out.

So I recommend that somebody who has a great idea while they are working a corporate job, skip all projections and just start burning the midnight oil, weekend oil, lunchtime oil, whatever it is, somehow working that idea while they still have that income from the corporate job. And once their big idea has proven itself by providing an income that's the same level as their job, then the quit the job, because then it's not a giant cliff jump. It's just stepping from one platform to another platform at the same level, and they're doing so onto a platform that's proven itself.

Projections in business are awful, especially for amateurs. And anyone starting out is an amateur by definition. So just avoid the potential to blow it in your projections by making the idea prove itself. Then you can make the leap.

Peggy: I guess the other twist on that, if you follow your book, is that they could also change their lifestyle. You know, get rid of the fancy car, get rid of the big house, make other choices so that they could live within a smaller income too.

Jason: Yeah, if the change someone is making is not so much financial, but lifestyle or personal gratification, then that's true. Sometimes the best way to be happy is to just throw off all of the debt. So you're right, Peggy. Downsizing the monthly requirements is another way to be able to walk away from the job. But what I was talking about before is more along the lines that if you were hoping that your big entrepreneurial idea or career change idea in your own business can be enough so you can continue in your same lifestyle, you should make the idea prove itself by matching your income before you let that income go.

Michael: So what you mean is that if you don't want to remain financially stupid, your idea better be really good and you better prove it works before you quit your job.

Jason: [laughing] Yeah, I think so. You know, I'm a big fan of making ideas prove themselves. I just can't stand pie in the sky projections. And they're so unnecessary. Just do it and let's see what happens. Don't project, just record. I prefer history to forecasting.

In fact, that's our official policy at Red Frog. Emily wants to expand to another location in Colorado, and so do I. We'd like to get another shop in Boulder, which is next to Longmont. And she was asking me when we first started out, and I was providing the money to start it out, how will we know when we have enough money to go to the new shop? It's very simple. As soon as profit from this shop has provided enough money in a bank account to start the new shop. Until this shop has done well enough to start a new shop, How can we be confident in the prospect of a new shop? So I really am a big fan of this idea of achieving good history, not rosy forecasts.

Peggy: It sort of reminds me though of what Michael is always saying. If people would only listen to him... If people would only listen to you...

Jason: Yeah, they never will, unfortunately.

Michael: I've learned that too.

Jason: Honestly I think that's a big problem with this book, even though I like Financially Stupid People, the book, and I think it's important. But part of the problem is that it's a classical example of preaching to the choir. I mean most people who read financial books are financially responsible. That's why they're interested in reading financial books. So the best kind of things to write for that crowd are things about how to improve your already pretty sound finances. Because the truly financially stupid people are not going to read financial books.

Peggy: That's right. I almost didn't read it because of the title.

Jason: Yeah, lesson learned. Luckily it wasn't a complete bust, but I had really high hopes for that and didn't quite get there, but you know, that's par for this business.

Michael: Well, this has been good. It's been good to talk to you, Jason.

Guy: It's been a pleasure.

Jason: Yeah, it's been fun.

Our monthly radio show: Designing a Creative Life

|

And now it's like, "Oh those fun times growing up," but at the time, there were some pretty intense feelings.

And now it's like, "Oh those fun times growing up," but at the time, there were some pretty intense feelings.

You remember the urgency following March 11 last year. That atmosphere is not one you encounter very often. So the organization was completely different from what you would find in a corporation.

You remember the urgency following March 11 last year. That atmosphere is not one you encounter very often. So the organization was completely different from what you would find in a corporation.

People were already saying on TV news, "We need socks. We need socks and underwear." That's what people said a lot. We figured "Socks for Japan" was easier to pull off than "Panties for Japan," so that was our focus. [laughter]

People were already saying on TV news, "We need socks. We need socks and underwear." That's what people said a lot. We figured "Socks for Japan" was easier to pull off than "Panties for Japan," so that was our focus. [laughter]

At least with our volunteers, but I think you could pull this off in other places in Japan. You could say to somebody, "Alright, we've got 2000 pairs of socks here that we need to sort tonight. We need people here to do it tonight." It gets done tonight. There was just this fabulous efficiency and dedication to it. There were no hard feelings, none of the usual things you hear people complain about in a corporation. But I think that's not because of the way we set it up, but because of the circumstances that caused us to set it up.

At least with our volunteers, but I think you could pull this off in other places in Japan. You could say to somebody, "Alright, we've got 2000 pairs of socks here that we need to sort tonight. We need people here to do it tonight." It gets done tonight. There was just this fabulous efficiency and dedication to it. There were no hard feelings, none of the usual things you hear people complain about in a corporation. But I think that's not because of the way we set it up, but because of the circumstances that caused us to set it up.