|

Michael: That was quite remarkable. Actually, there are a lot of remarkable videos out there of your work—but anyway, it seems to me like both jazz and the classical exposure in Japan have...

Kenny: Oh yeah! and actually all the people performing—tomorrow nights performance is like two groups coming together. So the On Ensemble is a group of—well, they're in their 30s, doing real creative work, all have spent time in Japan. Two of them studied for a long time with me in Japan, and I'm real proud of what they're doing. And then my ensemble, which is also younger people—the flute player, Kaoru Watanabe used to play with this group called Kodo, and he's a really amazing flute player, went to Manhattan School of Music, and actually knows jazz and can improvise. The one playing vibraphones now, Eien Hunter-Ishikawa, was actually born in Japan, grew up in Kawai and Michigan, and has a real interest in Taiko and drums, and now he's living in Vancouver, and I flew him down for this. And the violinist, Charlene Huang—this is the first time I've worked with her. We had met before, and I asked her to do this performance.

Peggy: So how does that happen? Obviously some you know—you had seen her before? so you invited her?

Kenny: Yeah, so basically we just had Monday and Tuesday to rehearse in LA and put this together. But the On Ensemble I've collaborated with before. They were a guest in my 35 year anniversary concert in LA last year, and then we did a joint performance at the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts in '09. So I'm familiar with their work and also they're familiar with my work. So at Cerritos I did one half and they did one half and then we did one thing at the end. This time we're kind of mixing our pieces.

Michael: At one level it almost seems like you never really had to make that decision between jazz and Taiko. I mean, yes you did, but...

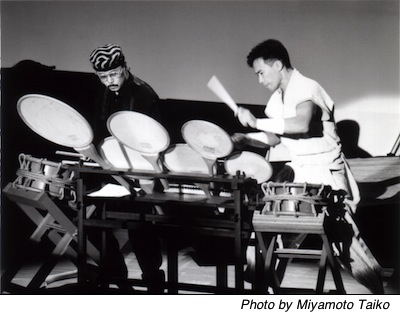

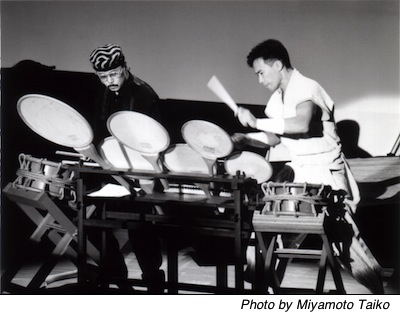

Kenny: Yeah, I call it my Taiko set, a set of three drums, the way I approach it is similar to a drum set. And it's obviously been a big influence on the younger generation too, because almost everyone in this group has a similar setup. But we're doing Taiko pieces as well, and one of my pieces called Symmetrical Soundscapes, which was originally a duet—we're going to do that with seven people to close the first half. It's going to be a special arrangement for seven.

Michael: I've heard that piece. It's amazing!

Kenny: I'm one of those people. I'm never quite satisfied. I always think something could be better, but on the other hand, I never feel too good or too bad about something that's already past. Whether I totally blew it and should feel like hell, or I did an incredible performance and got a standing ovation, to me, to dwell on either is not healthy. You've just got to keep moving forward.

Kenny: I'm one of those people. I'm never quite satisfied. I always think something could be better, but on the other hand, I never feel too good or too bad about something that's already past. Whether I totally blew it and should feel like hell, or I did an incredible performance and got a standing ovation, to me, to dwell on either is not healthy. You've just got to keep moving forward.

Michael: I'd like to talk a little bit about family, and keeping the right balance. In some ways this is more stressful than for a visual artist who has their own studio space and most of the work happens there. For you it's literally all over the map.

Kenny: Yeah, its really a challenge. I have to give a lot of credit to my wife, Chizuko, who was home with the boys when I was on the road, and helping raise the kids and keeping our school together because we have a school in Honolulu called the Taiko Center of the Pacific where we offer public classes. So when I'm at home I'm usually teaching and involved in that, but when I'm on the road, my wife and students keep both the performing group and the school going.

Peggy: So you're on the road how much of the year?

Kenny: Before it used to be half, but now it's more like three to four months of the year.

Peggy: This is part of the Cal Poly Performing Arts series. How did you find them, or did they find you?

Kenny: The On Ensemble has an agent, and I have an agent—they're two separate people, but when we did this project at Cerritos, On Ensemble's agent and my agent thought it was a good thing, so they pitched it—they have these arts presenters like Western Arts Alliance, where they bring presenters and agents and artists together, so they pitched it, and both San Luis Obispo, and next year in February, we're going to Texas A&M to present this show.

Michael: So it sounds like a big piece of your promotion and marketing is through a booking agent.

Kenny: Yeah, I just connected with her—I've known her for many years because she was the presenter at Maui Arts and Cultural Center, and she switched to become more on the agent side, so she knew I was looking for an agent.

Peggy: Did you have an agent before?

Kenny: I had one in the early '90s but it didn't really work out. And the industry's really changing. A lot of people are representing themselves these days. But if you have a good agent, they have access to more markets than you would as an artist.

Peggy: So you were doing it yourself before?

Kenny: Yeah, or just word of mouth.

Michael: Well, it seems to have worked. For one thing, you have been able to keep it going, and another thing is, people know who you are.

Kenny: People say, "Do you ever think about quitting?" and I say, "Every day." and then I think about what I would do, and then I say, "I guess I'm gonna play again." There's nothing I'd rather do, but also, I have no other life skills. I could be a gardener, maybe.

Peggy: That was one of my questions—did you ever think about doing anything else? You started so young.

Kenny: Yeah, the only thing I ever possibly considered was being a doctor. Or maybe a teacher. Or at one time I thought it would be pretty cool to be a forest ranger, because you could just live out in the—you know.

Kenny: Yeah, the only thing I ever possibly considered was being a doctor. Or maybe a teacher. Or at one time I thought it would be pretty cool to be a forest ranger, because you could just live out in the—you know.

Peggy: Weren't you a biology major at one time?

Kenny: No, I was never a science major. I was social science. But I still feel like doctors—your dad was a doctor wasn't he?

Peggy: He was a dentist.

Kenny: I think music has healing aspects to it. Not only for the performers but for the audience members, so I think there's a definite connection there.

Peggy: And you are a teacher.

Kenny: Yeah.

Peggy: So did that help support you all—doing the teaching?

Kenny: Well yeah, definitely. When I'm on the road a lot of the Taiko groups—there are so many Taiko groups now—they have me come in and do workshops. Like this morning we went to a school and did a workshop. Tomorrow morning we're doing a school show, so that's a big part of it. And then in our school that we established in Honolulu, I wanted the classes to be public and I wanted them to start at the age of five. We were one of the first programs through the Kapiolani Community College that offered that. Usually continuing education is for adults. They made an exception. And we've had people as young as three or four in our classes too. Our oldest student was 83.

Peggy: Wow, that keeps you young.

Kenny: I think it keeps you young on one hand, and it also makes you old fast on the other hand, because of the work involved. It's not only physically demanding, but it's also all these schedules and all these things going on.

Kenny: I think it keeps you young on one hand, and it also makes you old fast on the other hand, because of the work involved. It's not only physically demanding, but it's also all these schedules and all these things going on.

Michael: I'm not sure if that makes you old. It probably keeps you sharp.

Kenny: It could be.

Peggy: Yeah. The physical—you have to be so fit to do what you do. I told Michael one of my memories was of you dragging me around campus at UCLA to go running, and I don't do running.

Kenny: I think I finished in 5 quarters. I just wanted to finish. I wanted to change my Major to music, but at that time, not only did they have a minimum credit, but they had a maximum credit, so if you started something, they didn't want you to keep changing your major. It was too late to change to music, so I picked political science because my credits could transfer the easiest, and I could take more music classes that way.

Peggy: So did you take traditional music classes?

Kenny: I took theory, I took a percussion class, I took Indonesian Gamelan, I took Indian music, African drumming. UCLA's ethnomusicology is amazing.

Michael: We touched on this at the very beginning, but I want to be sure we exhaust whatever is in it. The time that you went to Arizona, you were working at a public health hospital.

Kenny: I was working on a Native American Indian Reservtion called the Colorado River Indian Tribes, along the border between Arizona and Colorado. And it was about 80% Mojave, about 18% Chemehuevi, and a sprinkling of families from Hopi and Navajo. I actually got this placement through an organization called Save the Children Foundation, which is a charitable organization, but I was placed to work with a public health worker. So I was working with youth groups and alcoholism groups.

Michael: Were you exposed much to the culture beyond the hospital and the job?

Kenny: Oh yeah! It was an incredible experience. At that time the Viet Nam war was going on and we were all involved in the anti-war movement, and it was really frustrating being in Santa Cruz because everybody wanted to do something. We felt like we were so isolated from reality there. So being very naive, I wanted to do something. I wanted to help the Native Americans, but of course they ended up helping me. Because it was after that experience that I realized that I needed to get into my own culture, and really discover who I was.

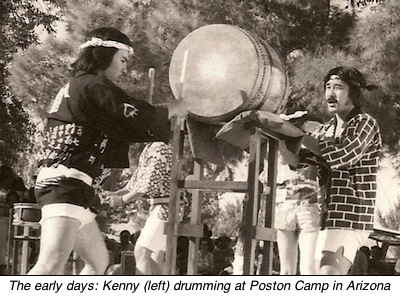

Michael: And this was right at the Poston Camp. What an amazing synthesis for you.

Kenny: Yeah! It was an amazing experience there. Because during the war, Poston became the third largest city in Arizona all of a sudden, after Phoenix and Tucson. And I heard a lot of stories from the Native Americans. You know, you hear about it from the US Government side or from the Japanese American side, but I'd never heard it from the Native American side. And they had exchanges, like there would be baseball games, they would exchange cigarettes and food.

Kenny: Yeah! It was an amazing experience there. Because during the war, Poston became the third largest city in Arizona all of a sudden, after Phoenix and Tucson. And I heard a lot of stories from the Native Americans. You know, you hear about it from the US Government side or from the Japanese American side, but I'd never heard it from the Native American side. And they had exchanges, like there would be baseball games, they would exchange cigarettes and food.

Peggy: I've seen photos of it now, but we didn't know about it back then.

Kenny: And the Japanese were the first ones who started using irrigation. And for the first time they started seeing vegetables growing—they thought it was just a desert all this time. So after that, after World War II, and the Japanese left, they started leasing out their land and now it's one of the biggest agricultural areas.

Peggy: Yeah, now it's where all the tomatos and everything come from.

Kenny: That story is pretty amazing.

Peggy: For some reason you knew that my mom was at Poston, because in your letter you said, "Tell your mama the old mess hall and gym and a bunch of buildings from Camp One still stand." Where were your parents?

Kenny: They actually evacuated voluntarily because they didn't have kids. And they went to Idaho, but they were a burden to the relatives and they ended up in Utah.

Peggy: In camp or not in camp?

Kenny: Not in camp. My mom said it was actually worse outside of camp than in camp in some ways.

Peggy: Oh, probably, because people probably weren't very nice to them.

Peggy: So you were at Kinarra Taiko for how long?

Kenny: I was with them '75, '76, and then after I graduated from UCLA I moved up to the city with Tanaka-san in San Francisco.

Peggy: And you played jazz at night?

Kenny: When I lived in San Francisco? Yeah, I played in a club six nights a week.

Michael: So that was your "day job".

Kenny: 9PM to 2AM.

Peggy: Who did you play with?

Kenny: It was one of the clubs in J-town, and it was actually with this really great piano player, and we would have to play to these Japanese people and they would come up and sing Karaoke, and we were the live music in between, and we would play jazz. It was really funny. So that was my first job after graduating from college. I don't think I ever had any other job. I did teach English in Japan and a few other things.

Peggy: So when you studied in Japan, how were you able to afford that?

Kenny: I did get a small JACL scholarship. And then part of it was teaching English when I first got there, and then later I became a professional Taiko player. I was part of a group, so I was getting paid. so that was from 1982 on. It was a struggle then, and it's a struggle now. I wouldn't necessarily recommend it.

Michael: So what's next? What's ahead of you?

Kenny: There's still a lot of people I'd like to collaborate with. Not just musicians—theater people, people in film, and dance. A lot of the collaborations I've been doing are really interesting. There's one coming up next year called "Taiko, Tabla, and Timbales", combining myself and Abhijit Banerjee who is the leader of that percussion group—he actually brought me to Calcutta two years ago to perform with his group—and the third person is John Santos,

he's the leader of a group called The John Santos Sextet.

He's a Latin percussionist from the Bay Area, really top notch. So the three of us are gonna collaborate, and write new work for each other as well as perform solo and duets and as a threesome.

Peggy: How do you know Santos?

Peggy: How do you know Santos?

Kenny: I actually met him through Akira Tana, a jazz drummer. And Akira put this group together for the Stanford Jazz Workshop. It was his quintet but he also had Ndugu Chancler, John Santos, and myself as his guests. So you get a kind of a percussion quartet. So I always kept in touch with John, and when I had this idea of combining these three things, he was one of the first people I wanted to work with.

Peggy: So you're performing, you're teaching, you've got family, and travel—when do you find time to compose?

Kenny: It is hard to find time to do that. Sometimes you've just got to make the time, or sometimes when you've got a quiet time, or a lot of times there'll be a deadline, like everybody else. You have a concert coming up, you have to present new work, and all of a sudden you get productive.

Peggy: Well especially if some other guy is waiting for it, I guess.

Kenny: Yeah, actually before the end of the year there's a couple of pieces I need to finish up.

Michael: Any regrets? anything you would have done differently with hindsight?

Kenny: I don't think there's anything I would have done differently—maybe work harder.

Michael: You've kind of answered that already when you talked about always moving forward and not worrying about what wasn't perfect in the past. What would you tell someone who is just starting out?

Kenny: I would tell them to practice hard, I would tell them to never give up. Someone told me early in my career, "You're never as good as they say you are. And you're never as bad as they say you are. And if you can maintain that balance and keep moving forward you'll survive.

|

Kenny Endo is at the top in American

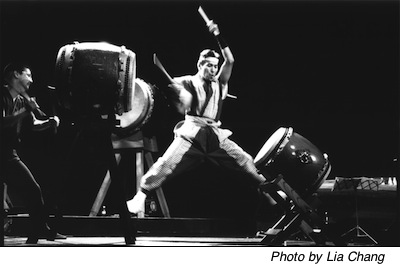

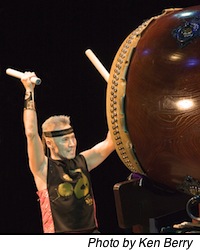

Kenny Endo is at the top in American  Kenny: I always loved drums. For example, when the parade would come near my house I would run out just to hear the drums go by. So I liked to feel that vibration. I used to mess around when I was three of four, and when I was nine, I started taking lessons. At my elementary school, luckily there was a music program, so I took drums, and in junior high I started playing drum set and got into the orchestra. I started playing rock music—so the drum set was my first main instrument, and I played that pretty much the whole time until I moved to Japan at the age of 27.

I had started doing Taiko at the age of 21. I was living in San Francisco, studying Taiko with

Kenny: I always loved drums. For example, when the parade would come near my house I would run out just to hear the drums go by. So I liked to feel that vibration. I used to mess around when I was three of four, and when I was nine, I started taking lessons. At my elementary school, luckily there was a music program, so I took drums, and in junior high I started playing drum set and got into the orchestra. I started playing rock music—so the drum set was my first main instrument, and I played that pretty much the whole time until I moved to Japan at the age of 27.

I had started doing Taiko at the age of 21. I was living in San Francisco, studying Taiko with  Kenny: Oh wow! You were on that trip?

Kenny: Oh wow! You were on that trip?

Kenny: A dentist, yeah, and one of my sisters is a pharmacist. But I was the youngest, so I just did my own thing. Actually my brother was really into art, and we had this discussion one time, and he said, "I'm going to be a dentist, and I like doing my projects, my art and wood work. I'm going to just work four days a week, and then I want to have a long weekend to do that". And he actually did set up his business from the beginning to work four days a week. But I said, "Well, I love playing music—I'm just gonna do it. I don't want to worry about any other job. So we had a different philosophy. And of course, having a straight job is more stable. You know, it's more security. So it's definitely a tradeoff.

Kenny: A dentist, yeah, and one of my sisters is a pharmacist. But I was the youngest, so I just did my own thing. Actually my brother was really into art, and we had this discussion one time, and he said, "I'm going to be a dentist, and I like doing my projects, my art and wood work. I'm going to just work four days a week, and then I want to have a long weekend to do that". And he actually did set up his business from the beginning to work four days a week. But I said, "Well, I love playing music—I'm just gonna do it. I don't want to worry about any other job. So we had a different philosophy. And of course, having a straight job is more stable. You know, it's more security. So it's definitely a tradeoff.

Michael: Are they showing any signs of interest?

Michael: Are they showing any signs of interest?

Kenny: I'm one of those people. I'm never quite satisfied. I always think something could be better, but on the other hand, I never feel too good or too bad about something that's already past. Whether I totally blew it and should feel like hell, or I did an incredible performance and got a standing ovation, to me, to dwell on either is not healthy. You've just got to keep moving forward.

Kenny: I'm one of those people. I'm never quite satisfied. I always think something could be better, but on the other hand, I never feel too good or too bad about something that's already past. Whether I totally blew it and should feel like hell, or I did an incredible performance and got a standing ovation, to me, to dwell on either is not healthy. You've just got to keep moving forward.

Kenny: Yeah, the only thing I ever possibly considered was being a doctor. Or maybe a teacher. Or at one time I thought it would be pretty cool to be a forest ranger, because you could just live out in the—you know.

Kenny: Yeah, the only thing I ever possibly considered was being a doctor. Or maybe a teacher. Or at one time I thought it would be pretty cool to be a forest ranger, because you could just live out in the—you know.

Kenny: I think it keeps you young on one hand, and it also makes you old fast on the other hand, because of the work involved. It's not only physically demanding, but it's also all these schedules and all these things going on.

Kenny: I think it keeps you young on one hand, and it also makes you old fast on the other hand, because of the work involved. It's not only physically demanding, but it's also all these schedules and all these things going on.

Kenny: Yeah! It was an amazing experience there. Because during the war, Poston became the third largest city in Arizona all of a sudden, after Phoenix and Tucson. And I heard a lot of stories from the Native Americans. You know, you hear about it from the US Government side or from the Japanese American side, but I'd never heard it from the Native American side. And they had exchanges, like there would be baseball games, they would exchange cigarettes and food.

Kenny: Yeah! It was an amazing experience there. Because during the war, Poston became the third largest city in Arizona all of a sudden, after Phoenix and Tucson. And I heard a lot of stories from the Native Americans. You know, you hear about it from the US Government side or from the Japanese American side, but I'd never heard it from the Native American side. And they had exchanges, like there would be baseball games, they would exchange cigarettes and food.

Peggy: How do you know Santos?

Peggy: How do you know Santos?