The Windhook Interview—Kathy Erteman

Peggy has known Kathy Erteman since grade school. The two of them are good friends and this interview has been one that we looked forward to doing since the very earliest conception of Outside the Lines. Kathy is one of those rare artists who has always done her art full time. And she has spent the past 19 years successfully navigating the pressures, opportunities, and hazards of being a full time artist in New York City.

We did this interview a couple of weeks before the arrival of hurricane Sandy. When the hurricane came, Kathy was (and at the time of posting still is) in Tibet, launching a 2 year grant project that you will read about below. She is safe, and while her studio is on 18th Street, just half a block from Union Square in Lower Manhattan, it's on the second floor above any flood threat and next door to a fire station.

Peggy: Kathy, years ago, you and I took ceramics in high school. Was that your first venture into ceramics? How did you get started?

Kathy: I touched clay many times as a child before that tenth grade ceramics class, but the minute I started making pots on the wheel in that class, I felt like I had a burst of religion, and had come home. I thought, "This is it." I wanted to spend my every waking hour making pots. It hadn't really occurred to me to pursue ceramics although I did a lot of different art related things as a child. What else did I do? Many different crafts, textiles, sewing, life drawing, but it never occurred to me to work with clay. I guess because you couldn't really do it at home. It required equipment and it was messy for our suburban reality.

Michael: Let's take a minute and get back to that suburban reality. You and Peggy have known each other for a long time, not just since the tenth grade. Take us back, beyond the time when you knew Peggy. Tell us about where you're from and a little bit about how you came into this world.

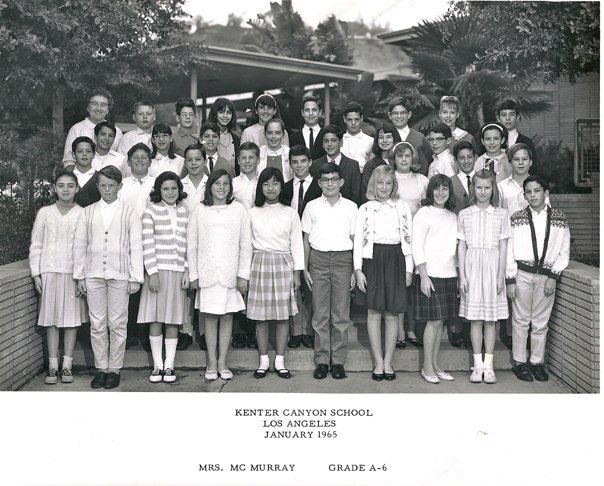

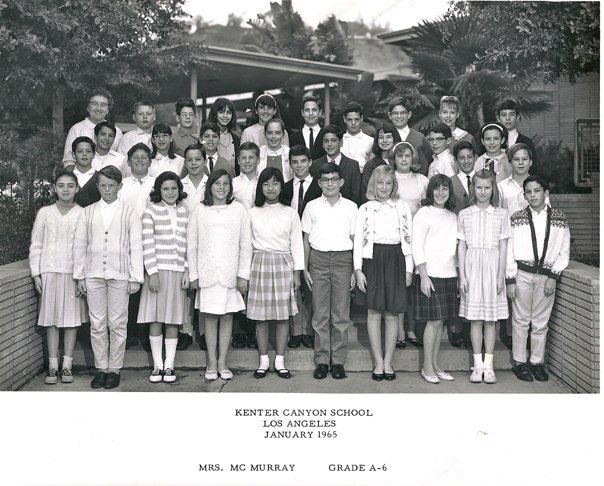

Kathy: Sure. And I'd love to talk about an earlier experience with Peggy. I grew up in Los Angeles. I was born in Los Angeles California to European immigrants. My father was from Holland and my mother was from Austria. We eventually settled in West Los Angeles, and lived in a very modest suburban home and my parents were trying to assimilate, live the American dream, like everybody else at that time. It was a bit challenging for me with the easy-going Southern California attitude, and having parents with accents and a strict formality. We ate different food and had different ways. At the time, I didn't really like it that much.

I met Peggy when we were in fourth grade. We were both struggling with math. We were struggling with long division. We used to do our homework together. Some years ago I found a piece of paper preserved in a kids storybook with some very incorrect math results on it. It was one of our homework pages from that time. We used to lie on the floor and do the homework using a very large storybook as our hard surface to write on.

I remember Peggy's family very fondly. They had a beautiful modern house. One of the things I noticed as a kid growing up was the modern architecture in our West Los Angeles area known as case study house now. I was very much visually oriented even then. My mother was a fashion designer. We had art around our house and modern furniture, some brought from Vienna. I think those things started to tune my eye for an aesthetic that I later developed. I absolutely loved the Sonoda house, and still think about its open modern floor plan, big windows, and asian accents. It seemed very conducive to living a harmonious life. I thought about those things then.

Peggy: I have very vivid memories of being at your house, doing our math homework on the floor of your room, and then eating dinner with your family. I was always so thrilled. Your mother was a beautiful, elegant woman. I remember her being totally dressed up in a dress and heels and serving—to me it was very elegant. I guess it was probably a traditional Austrian or Dutch way of eating, where you had soup and salad and your main course and desert, and I always thought that was fabulous.

Kathy: And I was dreaming of eating spaghetti in front of TV like everyone else at school! My mother was dressed up like that because she worked, which was different from the norm of what was going on then. You know, a lot of the mothers in our neighborhood were stay at home moms.

Peggy: So she was a fashion designer?

Kathy: Yes. She went to Art Center in Pasadena and was trained as what they then called a commercial artist. She did fashion illustration and graphic design for fashion before she was a fashion designer. While we were growing up she was a fashion designer at the family company Marguerite Dexter. Every morning she would get dressed up formally which was unusual for LA and drive downtown to go to work.

Michael: So you guys knew each other from fourth grade, and then in tenth grade you had this ceramics class, and then what happened? Did you immediately focus on that sort of thing, or did it take you a while to get there. I guess partly I'm thinking about where you went to school after high school and what the path was for you to make it a career.

Kathy: Actually, it was a pretty straight path. When I was in high school, after that one class that just wasn't enough for me. I discovered a private ceramics studio that you could join and work as a member 24/7. It wasn't for kids, it was for adults. Much to my surprise, my parents granted me permission to have a membership. I spent all my free time there. You could go in and work on the wheels anytime. They had great glazes and fired the kiln often. There were 2 owners—one was an artist, and the other one was an inventor and the wheels that we worked on were the prototypes for the wheels that made him famous later: Robert Brent potter's wheels.

Michael: So Robert Brent was one of the owners of the studio you worked in?

Kathy: Yes.

Michael: Oh, wow!

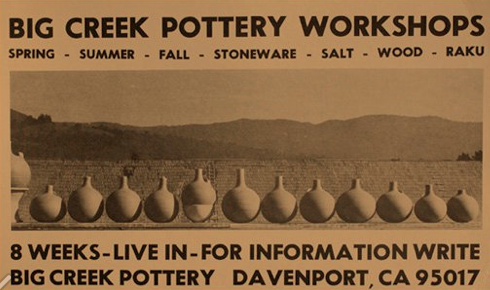

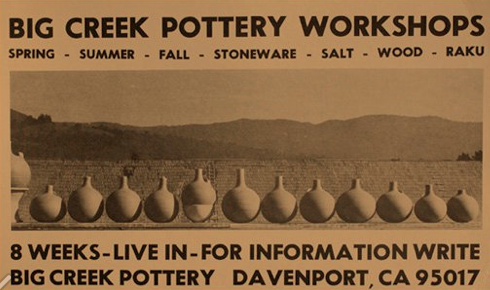

Kathy: The other owner was Tony Evans who is still making pots today. It was a special time in the development of studio ceramics in California and in my development. The summer after graduating from high school I attended a nine week pottery workshop in Davenport, California near Santa Cruz It was a very rigorous workshop. Making pots 8 hours a day —plate, cup, bowl—making hundreds of each shape. It was about design, it was about technique, and it was also about the lifestyle. Living the life of a potter. It was a very beautiful, romantic setting. But I only intended to for that to be a fun summer experience. I assumed I would just drop off and pursue something academic at UCLA. By summers end, nine weeks in this idyllic situation I naturally wanted to stay on there. Tony Evans and Robert Brent from the Potters Studio in West LA were moving up to northern California to continue their lives there. I wanted to do the same and continue my life as a potter and forget about college. But I didn't really have the courage to do that, so I went to UCLA which I didn't like it at all. I changed schools and found myself back in a ceramics class along side my academic studies. I kept making pots. When I was very close to graduating from Sonoma State College, I thought, "I am not passionate about what I'm pursuing."

Michael: What were you studying?

Kathy: Sociology and literature. Nothing was jumping out at me in the academic world. Perhaps teaching, but that wasn't really very compelling. So I had a talk with myself, and reasoned, "If I'm spending all my time making and thinking about ceramics, I should just pursue it as my life path."

And at that point, I felt I didn't know enough to graduate in any field. I looked around, and there were two choices of schools that had BFA programs with a specialization in ceramics. One was Cal State Long Beach and the other Alfred State University. One on the east coast and one on the west coast. I knew that Alfred was the best school, but it was far too intimidating to go all the way to New York, so I applied to Cal State Long Beach. I was accepted, and I spent a very rigorous year and a half with a formal art education and a fantastic program. It was a very well rounded: ceramic sculpture, throwing, glaze calculation, ceramic art history, as well as painting, drawing, as well as some industrial arts and design.

That sent me on my way well equipped with skills , and again, when it was time to graduate, I thought, "I'm not ready to be an artist in the world." First I wasn't ready to graduate because I didn't have a proper education, and now that I did, it was that I didn't know anything about the practical side of being an artist. However I never again questioned my direction. I was certain that I was going to be an artist, and I couldn't wait to get out of school, set up a studio and begin. I even had a picture in my mind of what that would look like.

Michael: As you're talking, it comes to mind that there's always a reason that you should prepare more. And that ends up being an excuse not to jump at some point. It sounds like you finally got to the place where it was, "OK, time to go."

Kathy: Yeah, there was a little procrastination, but it was the case that practical wisdom was absent. Today students go to residencies and have internships upon completing their MFA to delay jumping, as you say. We all can benefit from an internship for the practical stuff.

There was no professional development then like the internships available now. I couldn't wait to get out there. I was done with school but felt that I didn't really have the practical wisdom. All of my professors were men, and they were all academics not studio artists . Fantastic as instructors , they were not role models for a young woman artist in the 70’s. Right around the time I was about to graduate, some people I knew in LA started talking about Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party, and told me that she was looking for people to work on the ceramic aspect of the project. I thought, "Wow how great! Judy Chicago is an artist in the world. She knows how to talk to the plexiglass fabricator, and be taken seriously by the guy in the hardware store, the gallery dealers, the collectors. I can learn a lot from her. That's what's missing." During the time immediately after graduating I had a few part time jobs. Part time teaching , a job in a ceramic studio, and then I started working in Judy Chicago's studio a couple of days a week. It was like an internship and I kept my eye very closely on Judy Chicago.

Peggy: How long were you working on that project?

Kathy: It was two years, from 1976 to 1978 when the project was completed. As anybody who's worked with Judy Chicago will tell you, it wasn't easy, but I learned a lot about working in a group, and a lot about myself, and it did everything it needed to do. But it also launched me into the world. Not that she gave me a leg up, but I could now go into a gallery and talk to the dealer and say, "I've just finished working with Judy Chicago on the Dinner Party," and the door was open.

I already had a studio at that time. My biggest fear after graduating from Cal State Long Beach, was that I would just get swallowed up by life and would never be an artist, would never have a real studio I felt an urgency to set up a studio right away. So I pretty much made sure that I got a studio right then. I rented an industrial space in Signal Hill, California, a former model railroad clubhouse. I didn't spend much time there because I was working several jobs to pay for it. That's no different from any young artist today.

As time went on, I worked less at other jobs and spent more time in the studio. That took a few years.

Guy: There's something you said at the very beginning, Kathy, and I'd like to go back to that comment. You said that you had had a religious experience. Can you describe that?

Kathy: Well, I think it was a feeling of passion and wonder about the activity of making ceramics and that I had never felt that kind of enthusiasm before. I felt that there were so many possibilities that had opened up before me. The ability to make something out of nothing was very profound. That’s basically what I meant by a religious experience. It was a bit like being in love too. I didn't want to do anything else. I didn't even want to sleep. I wanted to be in the studio every waking hour. When I wasn't making pots I was thinking about them. Looking at books, trying to meet other potters, figuring out, how to get my other school work done so I could get back in the studio. For example then there were records, like books on cd, like Shakespeare on records. I could multi-task, be in the studio and listen to the homework books on record and save time on reading while making pots, then do my homework. I went into the engineering library to see if there were any books on ceramic engineering. Maybe I would learn more about glazes. I felt like I couldn't really throw myself fully into ceramics, I needed to do something academic but I felt like a religious seeker.

Another thing I should mention that had a big impact on me in the early days was an exhibition at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles featuring the work of Gertrude and Otto Natzler, who were a husband and wife creative force. They were both potters. Gertrude mainly did the throwing, Otto did the glazing. They were from Vienna like my mother. My family talked about them from time to time, and they were a bit of celebrities in Los Angeles.

They had an exhibition of their pots at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, the pots on covered pedestals and on the surrounding walls photographs of them working in the studio in their beautiful rustic home in the Hollywood hills. They were black and white photographs showing Gertrud and Otto at work in their studio, in their beautiful gardens, or entertaining guests casually. At that moment, I imagined how their life was constructed—They would work in their studio, they didn't have to get dressed up and get in their car and go to a job. They just got up in the morning and went to the studio and worked, filled the studio with pots, had an exhibition, sold all the work, went back to the empty studio, and began again. That was very appealing to me. I don't know if I really spoke those words until many years later, but that's what I carried around with me as my life role model. That exhibition was probably while I was still in high school.

Peggy: I did look at some of their work, and you can tell. So much of ceramic art that you see seems so influenced by the shapes of her pieces, and obviously all of the glazes that he developed. I guess everyone still uses them if they can.

Kathy: Well, I am sure they had their secret glaze notebook and others sought to replicate them but there was a lot of lead in glazes then and no one would use them today because of it. When I was in school, you were supposed to look at a lot of different kinds of work for influence and inspiration but Mingei Japanese folk pottery was emphasized. It is much more rustic than the European pottery of that era. I was always more interested in the Natzlers' type of work, and a Scandinavian aesthetic It wasn't until many years later that the whole ceramic community and maybe the applied art community as a whole appreciated the Natzlers, and other Europeans—Lucie Rie and Hans Coper and a few potters in southern California that were making that genre of pots . What became very popular was abstract expressionist sculpture in clay. That overtook vessels as a popular form of ceramic expression in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Many schools forbid students to make functional or vessel pots.

Guy: So Kathy, you say that you're a modernist, but when you are making things for the dining table, you also are adding a utility in there for ease of use. You've moved away from that since, but how did you incorporate utility and modernist into the same piece of work?

Kathy: I do think they go hand in hand. The modernist ethos is really a pared down aesthetic: simple lines, clean form, and utility really does factor into it quite a bit. When I'm designing tableware, whether I'm making it myself, or now, as I do some design for industry, where I begin is what will be served and who is going to be using it. I love to cook. I'm very interested in food, and I feel that anything utilitarian should be a backdrop for the prepared food. If it's a serving utensil, I try to think about how it will fit in the hand, how it will scoop the food . I very much consider utility. Also with glazes I consider what will look good with food. Maybe I like a blue glaze, but I know that food doesn't look good on blue, so I would save that for a more sculptural piece.

Michael: You have mentioned the industrial design aspect, and I want to end up there in a few minutes, but on the way there I'd kind of like to close the loop on your early history. I know you spent time in the East Bay Area, and you ended up in New York City. Give us the arch from college on.

Kathy: When I finished at Cal State Long Beach, my goal was to leave southern California as quickly as possible, and return to the Bay Area. Shortly after college, I met my future husband, and it took me a couple of years to convince him to move out of Los Angeles with me . We looked around the Bay Area, and ended up moving to an artist community, Benicia, California, which is on the east bay, about a half an hour from Berkeley. There were a lot of huge old warehouses available for rent -Cheap rent, lots of space. There was a large professional artist community. There were glass blowers, painters, some very well known ceramic artists, Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest ,and Judy Chicago who had recently moved to Benicia. It was through one of the other artists who had worked on the ceramic aspect of the Dinner Party, Judy Keyes, that I was introduced to Benicia.

We moved into a 6000 square foot warehouse in Benicia with a view of the water, and it was a great place to begin life as a studio artist. I lived there for 14 years. In the mean time, I was separated and then divorced, but continued to live and work in the studio. At some point I felt that I was ready to leave Benicia and wanted a new view. I look at my time in Benicia as living with a very supportive family, and then at a certain point it's time to leave the nest and go out into the world.

I started looking for different places to move to after I was divorced. I wasn't sure where that would be. I made frequent trips to New York connected to my work, and on one of those trips I came back and realized " No wonder I can't decide if I should move to Mendocino or Berkeley, or somewhere else in between. It is because none of them are right. It's New York. I was really comfortable in NY but it was also a scary notion. I loved the energy, the international aspect of it, the craziness. I always felt like a foreigner in California, even though I was born there. In New York, I finally felt totally fine about being me.

Michael: We came back to visit you in New York City a few years ago, and you are right in the thick of it. You're right in the middle of Manhattan—well kind of the south end of Manhattan I guess. I'm probably not the person to describe the details because I don't know New York City that well, but I tell you, it's really hoppin' where you live.

Kathy: Yes, almost too much for me after 19 years.

Peggy: Wow. 19 years.

Kathy: Yeah, it went by really fast. Where I live is the area called Union Square. which is considered downtown. Not way downtown, but downtown. Union Square has become the heart of downtown Manhattan. When I moved there it was still considered the photo district. There were a lot of drug dealers in Union Square Park, and there was still cheap rent. It was colonized by artists, photographers, and other creatives. Andy Warhol's Factory was in that Union Square area, Max's Kansas City too. I moved into the building that was known by other artists as the pottery building, (all the potters of my generation in New York City have passed through that building or at least knew somebody in it). This small building had lots of power, concrete floors, and cheap rent. There was historically a contentious relationship between landlord and tenant. Through what's called "A New York Story," I managed to get into this building and secure a long term lease. I had two very good friends that lived in the building, and with a wish and a promise, I renovated a floor that had been a photo silkscreen printing business, left abandoned and unrented for 10 years and a dirty wreck!

Peggy: Wow!

Image of Kathy's studio, compliments of Rita Harowitz

Kathy: Everybody has their own floor. There are 9 floors. They're small floors, but it allows one to live and work on the same floor, which is important if you're a potter, because there's always something you have to check at 11 or 12 at night. It's very convenient just to walk across the hall and check the kiln rather than get out, get dressed, and ride your bike up or downtown or get on the subway. I could imagine how I wanted to renovate the wreck of a floor because I had friends who were already living in the building and I could use their places as a model to expand upon.

Peggy: It's a wonderful space. I didn't realize there were other artists on other floors there. Your layout is wonderful, with the studio up front with those big beautiful windows. And then you have that very nice apartment living space behind it.

Kathy: Which is nice and quiet. There's a firehouse next door, but because it's a brick and steel building, you don't hear it at all.

Since that time, there are no other artists in the building. I'm the last one. There is one other tenant that has been there longer than I. The rest are all young Wall Streeters and some NYU students that all live as roommates, five or six to a floor, so it's really the end of an era. There are very few artists left in the neighborhood except the ones that have lived there as long as I have or longer.

It has become incredibly bustling. When I moved in, at night after dark, the grates went down over the commercial spaces, and there was no streetlight at all, and a bit scary, like one of those thriller movies. But now, it's a destination, and you can barely find a place to walk on the sidewalk.

Michael: I know when we were there, I don't think it ever slowed down.

Peggy: No. Restaurants everywhere, things going on all hours of the night.

Kathy: Yeah, the energy of New York is fantastic. But at a certain point, everybody seems to want to get away a little bit and recharge. They say that New York has a 12 year shelf life.

Guy: And you're at 19.

Michael: But you have a place to get away.

Kathy: I have place upstate. My nephew a NYU student from California recently asked me, after listening to my friends, "Does everybody in New York have a country place?"

"Well, not everybody, but unlike California, the country is relatively affordable." There are places you can go that are affordable even for an artist and it is almost a necessity at some point to be able to get away from the city and to regroup and rest. I had a sense of that even before I came to New York City and I thought, "If there's a way that I can get a place outside of New York in the country, I'm going to do it." I really worked on it.

My house is two and a half hours outside of New York, and I go there every weekend, and in the summer I live and work there full time.

Guy: Kathy, in the middle of all this, and with the success you've had with your work, do you do all of your own marketing, or do you have someone taking care of the business side of things?

Marketing methods have changed a lot, but I've always felt like it was very important to have great graphics, photography and writing. It should all be as well designed, and crafted, as the work and that has not changed for me. I try keep the same standards for marketing as I do for my studio work.

Guy: The reason I asked that, Kathy, is that you're able to get some really fine showings in some influential areas.

Kathy: Some of that is luck, but thank you. Over the years I have had some really good opportunities, and been able to be part of some really excellent exhibitions, and it's been really a privilege and also quite a bit of luck to be a full time studio artist able to support myself pretty much exclusively by the sale of my work.

Michael: well, you probably have a more impressive track record than most people we know personally. You are one of the few people we know who has been a full time artist— surviving in Union Square! That's pretty amazing. It's very remarkable that you have been able to maintain your lifestyle completely with your work.

Kathy: Thank you. I really have never known anything else. I never had a full time job. I've only known this as my reality. I needed to work 12 hours a day, or 18 hours a day, I just did whatever it took, working to the work. I think it was really helpful to not have anything to compare it with. There is a lot of stress. The financial stress has been at times tremendous. But I really didn't even think there were any other options for me so I just rode the wave.

Michael: That's probably the best thing that could have happened. If you did have options you might have taken them. I don't know, but maybe.

You teach, correct?

Kathy: I do teach. I didn't teach that much before I moved to New York, but when I moved here, I was invited to teach at Parsons School of Design, and also at Greenwich House Pottery. I continue to teach today at Greenwich House Pottery, which is a fantastic 100 year old ceramics school, internationally known with a rich history in the ceramic community. It's part of the City of New York, located in Greenwich Village. I teach one or two classes a week and enjoy it tremendously. The students are excellent. I sometimes do professional development workshops at universities, and at art centers. I really love sharing what I know, especially with advanced students. It's great to see somebody move their work along. At Greenwich House Pottery there's a great sense of community. People go to Greenwich House for pottery and community. The students are very dedicated. They might work as a lawyer or an emergency room doctor by day and have a very rigorous career but also are devoted to their long-term pottery practice. When they arrive at the studio, they leave their day behind, and are very focused on making pots. I am so impressed with their dedication and it’s very rewarding as a teacher.

Peggy: I remember going with you to one of your classes, and it was a real community. Your students had been together for a while, and you all fed off of each other in a very positive way. It was really a wonderful place. And I bought a really nice piece there. Was it Judith Galloway?

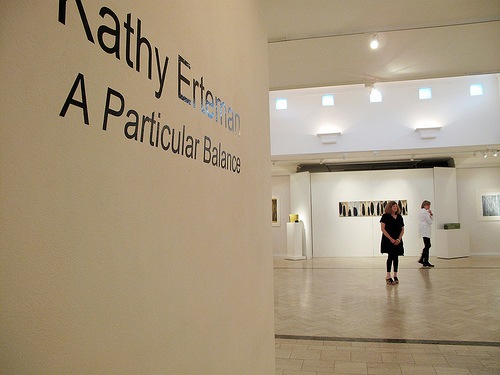

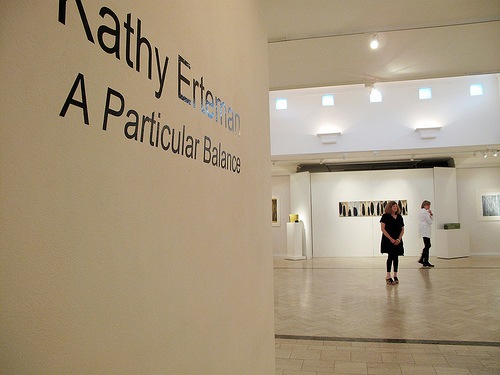

Kathy: Yes. Julia Galloway, her work is really good. There is also an art gallery at Greenwich House called Jane Hartsook Gallery for exhibitions with a new exhibit every month. A couple of years ago I had a solo exhibition there. I did a big installation work that needed a big space with high ceilings. It was a great launch pad for the new work that I'm currently doing.

Peggy: The photos of that were beautiful.

Kathy: That exhibition was called "Traffic Patterns." You can see some photographs of that on my web site.

Michael: How long have you been doing architectural ceramics? I know you were doing some of that when we were there.

Kathy: I think since 2005. I had been making vessels exclusively and wanted to expand my work, try out some ideas that had lingered in my notebook for a long time. Some of these were architectural site-specific installations for commercial , residential, public spaces. I embarked on a whole new experimental body of work. Wall pieces,both modular color squares, and paintings on ceramic tablets. The squares are three dimensional shapes in rich textured color glazes which I arrange in particular configurations. They can wrap around walls, occupy a floor to ceiling space or be tiny intimate installations. It was a whole new direction for me. I've had commissions, and a few exhibitions.

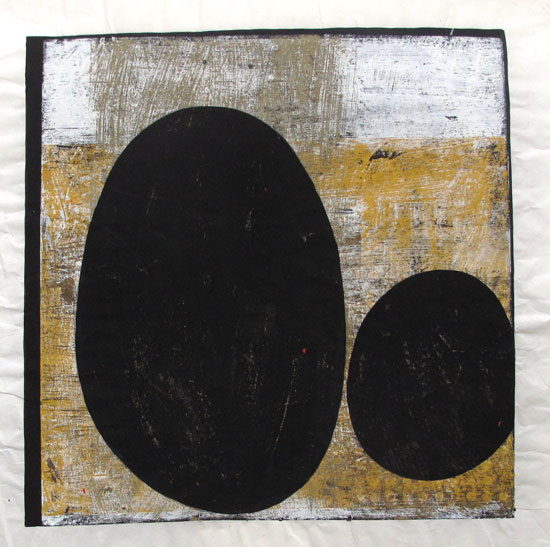

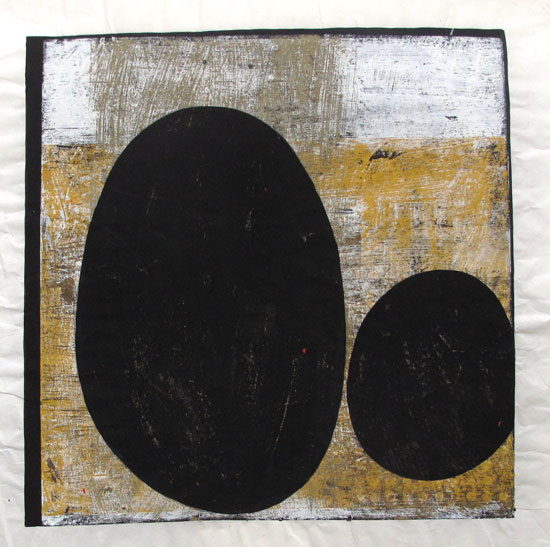

Working on these architectural pieces interestingly has led me to another body of work that is strictly works on paper. Monoprints and monotypes on mulberry paper, which is an Asian paper.

Peggy: When did you start those? I noticed them on your web site.

Kathy: I got a few commissions for my architectural works. I'm very interested in architecture and interiors, and the first few commissions I got scared me a bit. I thought, "I'm in over my head. Maybe I should work out some of these ideas on paper before I transfer them to clay and see how they look in space and get some more approval from the client." So that's how I got started working on paper. I got this big roll of mulberry paper, which has a very fibrous chalky surface a lot like clay.

I worked out some ideas true to scale on the paper before I worked on the ceramic pieces. I loved the immediacy. I didn't have to put anything in the kiln and get a disappointment, or breakage, or the colors change. Currently I work on both ceramic wall pieces, and on paper. I always ask myself the question now, "is this something that should be made in clay or should this stay a work in paper?"

So that's how that got started doing three different things: architectural wall installations, works on paper, and ceramic vessels. Well, maybe four, because I do design ceramics for industry but that's not the same as my work on my studio vessels.

Peggy: How did you get those architectural commissions?

Kathy: Some were architects I knew, and also I did a big marketing campaign, meeting architects through introductions by artists, designers and editors that know. I counted on everybody I knew to make introductions, and some of them panned out, and most of them didn't but I met a lot of interesting people along the way.

I made these really nice packets with photographs and ceramic sample pieces which I gave the architects after they made a studio visit . I did that for a couple of years continuously then took a break. Recently I've made a couple of presentations again.

I've bid on some proposals and didn't get them which is also part of it. That's a new part of my job working in the architectural arena. Especially in New York, there are some very dynamic architectural firms, and if you get to work on a project it's fantastic.

Peggy: What do you submit for a proposal? Is it sketches and images and a fee?

Kathy: There are a variety of ways depending on the project. They range from formal written proposal with model and sample board to verbal conversation. I've worked with Peter Marino, and they do a lot of retail stores on the high end like Louis Vuitton and Dior, and they do some hotels internationally as well as residential interiors. They will have an idea for the ceramic aspect of a project, but they don't exactly know what it should look like. It's a treasure hunt. They'll suggest a color or surface texture and shape category and I start making samples. There is a budget that allows me to make samples and do some experimental pieces. It is a collaborative effort and almost like one of those Iron Chef shows, where you have certain ingredients and you are working within a set of parameters: the colors, the scale, the textures, and go from there. until they say, "Oh, that's it. Great!" Then we formalize the details in writing.

Michael: We looked up Peter Marino after our conversation yesterday, and he's quite a colorful guy.

Kathy: He is!

Peggy: So are those wall pieces, or free standing, or vessels?

Kathy: It’s been vessels so far. I'd love to do some wall pieces for a Marino project . I make large three dimensional squares, 15 to 19 inches, each with a very glossy glaze . I think they would be great on the wall of a hotel lobby or a store. For public spaces they have expressed a concern about the fragility in possible scenarious like when a customer swings her handbag into a wall of squares, would they break?"

That's a reasonable question and I say with confidence no worries but there’s always the fragile issue with ceramics. I'm hoping we can do this kind of project in the future. Peter Marino is a ceramic collector himself and the entire office loves ceramics. These days I'm really enjoying the collaborations. Working in the studio is very solitary. To be an artist and get work done you have to isolate yourself. After all these years working alone in the studio I'm enjoying working with architects and designers, having a dialogue. I find it very invigorating, and energizing, to work collaboratively on commissions.

It’s the same with the tableware that I've recently designed for Crate and Barrel. Also a collaboration between the tableware buyers and the factories that produce it, the other departments within the company that are producing textiles to go with the tableware, and crafting the marketing story. It is very interesting to be a part of something larger.

Peggy: You have done work with Crate and Barrel before?

Kathy: I have. I've done some smaller projects over the years. Some lamps and casual tableware. This is the first time I've had a solid set of dinnerware that's coordinated with all of their dinnerware patterns.

Peggy: How did that come about?

Kathy: I designed this collection that they have named 18th Street Dinnerware, after my studio quite a while ago. The buyer comes to my studio once in a while when she is in New York. I set out my recent designs and that was one that she liked, asking me to send over some samples. They sat in the sample room for about 5 years until a design developer rediscovered them. The time was right! Usually an artist is 5 to 7 years ahead of the curve, and this design just didn't fit in with the larger story until recently. One day I received a call out of the blue and the buyer said, "We'd like to revisit your design." So I revised the samples. I make the samples on my wheel like I do the studio work. We sent the samples back and forth talked on the phone, made revisions, and once finalized the pieces were sent to a factory that produces them.

Michael: I never really thought of pottery as having drafts. But it sounds like you have first, second, and third drafts of things that go back and forth.

Kathy: Absolutely!

Michael: Very interesting. You've expanded my whole perception of this.

Kathy: Yeah, drafts and versions. Serving bowl draft two version three. [Laughter]

Michael: That's great. You came to see us a few years ago, and at that time you talked about a trip to Thailand. I think that was related to one of your Crate and Barrel projects. You've been to Thailand several times, haven't you?

Kathy: I have. I went strictly for my own pleasure. I had planned the trip, and then it turned out that I was doing a project with Crate and Barrel, so I did do some work while I was there, and visited the factories, and the product development agents for Crate and Barrel in Bangkok. I love visiting the factories, and I love work and travel combined. As a studio artist, you get to travel when you have a show and you get to see something other than the four walls of your studio. So I met all the people that were working on the project when I went to Thailand, and it was great fun. I've been back a couple of other times, and also visited with them. It's really helpful to know what the different factories can do when I'm designing something. I can say, "I think this would be a good factory for this collection." And I love traveling.

Peggy: And the food! You're a food adventurer as well.

Kathy: Yes, and especially an Asian food adventurer! I've also had the opportunity to work with Tibetan potters. There's an organization called Aid to Artisans that somebody introduced me to right after I moved to New York. They help traditional artisans around the world to grow their businesses, and adapt their craft to an international marketplace. That involves doing market readiness and some technical assistance. They're a private non-profit, and their business model has changed over the years. It was a simple assistance to artisans and now it's much more developed as the world has developed.

I told ATA I speak Spanish and could work with them in Peru, and around South America, but I'd really like to go to Asia if they ever had any projects there. They said, "Well, we hardly ever do, but we'll keep you in mind." One October morning a few years ago, when I was in my busiest work time of the year, I got a call from them ATA , "Would you like to go to

China in two weeks and work with artisans there?" My fist reaction was, "I can't do that now!" But I had a little talk with myself, and figured out how to do it. I got on the plane with very little information except that I was going to be working with some potters who made black pottery. My project was to last for 2 weeks. It ended up not being China at all, but the Tibetan Plateau. 12,000 feet. Everybody in this southwestern part of China is Tibetan. We worked intensely artisan to artisan and of course ate great food together. I had a very rigorous mission to accomplish. This was a collaborative project between Aid to Artisans and the Mountain Institute, and sponsored by USAID. My mission was to train the artisans in better craftsmanship, new designs and marketing. They were too basic to fit into other marketing programs that had been conducted in the region. ATA was looking for someone who was both a designer and an artisan who could work with these potters. It was a great fit. We got so much done in ten days and hoped to work together again.

China in two weeks and work with artisans there?" My fist reaction was, "I can't do that now!" But I had a little talk with myself, and figured out how to do it. I got on the plane with very little information except that I was going to be working with some potters who made black pottery. My project was to last for 2 weeks. It ended up not being China at all, but the Tibetan Plateau. 12,000 feet. Everybody in this southwestern part of China is Tibetan. We worked intensely artisan to artisan and of course ate great food together. I had a very rigorous mission to accomplish. This was a collaborative project between Aid to Artisans and the Mountain Institute, and sponsored by USAID. My mission was to train the artisans in better craftsmanship, new designs and marketing. They were too basic to fit into other marketing programs that had been conducted in the region. ATA was looking for someone who was both a designer and an artisan who could work with these potters. It was a great fit. We got so much done in ten days and hoped to work together again.

A couple of years later, the Mountain Institute asked me if I wanted to work with the potters again. So we applied for a State Department grant that was specifically for US/Tibet cultural exchange. We wrote this grant and we got it. It's called the Nwang Choephel Tibet/US Cultural Exchange Program. It's actually a Fullbright. That was in 2010 and I got to go back to the Tibetan Plateau, but only briefly. I met 16 Tibetan potters in the village and took them to another part of China, the birthplace of porcelain, and saw all different kinds of studios, and had some great adventures. Later in the summer, the Tibetan Potters came to the US and we went to Santa Fe so they could visit the Native Americans and see how they have managed their artisan careers very well while preserving their craft and their culture.

Peggy: Where did you go in Santa Fe?

Kathy: We went to the Indian Market. That was the main thing. There are so many similarities between the Tibetan work and the way they look, and that of the Native Americans.

Peggy: Did you say theirs was black pottery as well?

Kathy: Yes. We went to the Indian Market, and then we went to the Picuris Pueblo, and then the Taos Pueblo. Since it was all a bit hurried, we didn't have a chance to make plans in advance, but after we met, we decided we wanted to do a hands on exchange together in the future. The Tibetan potters also went to the East Coast, and to California, visiting artisans coast to coast—many of my fellow potters in New England, Washington DC, and New York City. It was a grand time for all of us. A bit sad though at the end. I thought I might never see or get to work with the Nixi Potters again. The grant was over and we went our separate ways. All contact ended. That was fall 2010. Then earlier this year, I got an email from the State Department announcing the call for the same US/Tibet cultural exchange grant. This time I applied for it with Aid to Artisans and we recently got word that we received the award. Now it's for 2 years. I'm really excited. We parted in a hurry last time with a lot of loose ends and no closure. Luckily we did scribble down our ideas for working together if there was a next time, so we get to pick up where we left off!

Michael: So it almost makes it like three years, because you've already done some of the groundwork.

Kathy: Yes, and we know exactly what we want to do. I'm hoping to go to China in a few weeks, as a short preliminary visit to make sure that the potters are still interested. It's important to me that they still want to work together and are interested in the same projects. Maybe they have some new ideas. We’ll talk, have a reunion then everybody will settle in for the long cold winter. In spring we will begin working together again.

Michael: That sounds really great!

Peggy: Yeah, very exciting. And Kathy, Before I forget, if you go to Santa Fe again, my cousins have connections to the potters at San Ildefonso Pueblo. They're all the family of Maria Martinez. So be sure and check with me if you're going back to Santa Fe. That would be a wonderful connection for them.

Kathy: We definitely are going there. The State Department is most interested in that aspect of our exchange. So I will definitely take you up on that offer. Thank you.

Peggy: That will be great!

Guy: Something I was thinking about, Kathy, how much change has taken place in your work since your Asian experiences, and what you've learned from that?

Kathy: Hmmm. That's a good question. It's really not that linear. But it did make me realize how the vessel tradition is very narrow. We all make the same shapes, over and over again with slight twists. I don't know that so far, I can see influence in the vessels that I'm making, but I must say that last year unbeknownst to me, a bright red-orange color crept into my work. I've never been a red person or a bright color person. It started with some works on paper, and I just went with it. I realized that it involves being around so much red in China . Bright red confetti from fireworks, the deep red color of the monks' robes, images of Mao an orange red. Just lots of red, always in company of black and white, which is my palette choice. That is the main way that I have been influenced. Earlier this year, the same kind of red color crept into some of my vessels.

Peggy: I saw that piece with the red. It was beautiful, that elongated vessel.

Kathy: : Thanks Peggy , and I didn't even see the connection between that vessel and some works on paper with red because after the works on paper are finished, they either go to the gallery or they get put into a flat portfolio, and I don't see them. I try to keep them protected from the dirt and the dust of the clay. One day I opened the portfolio and I noticed "Oh. This color is exactly the same on both ceramic vessel and print . Same palette, the same hues. There was about a six month time lapse between the works on paper with red and the vessels with red.

Peggy: We touched on this earlier, that you've always been a full time artist and that's how you've made your living. I know you mentioned that there have been, and continue to be financial hardships with that. But what do you think has kept you going all this time?

Kathy: Well, I'm not trained to do anything else. The job of a full time studio artist has so many aspects to it from marketing to floor mopping and accounting, the sheer work required to keep afloat keep one going. However the passion to create is like breathing. You almost can't do without it. That's definitely a very strong part of it. Also, the idea of having a job, for many years was terrifying to me. I imagined a kind of a mean boss and getting fired. I think there were some authority issues that I never wanted to face. When the going has gotten tough, in the last few years, I've talked to my friends about the possibility of having a job, and it sounded really good to me for the first time. And they said, "Yeah, for about the first two minutes." [Laughter]

Peggy: I think when we were in New York you were in that contemplative mode about going to work for someone.

Michael: Well, I clearly remember when we hosted you at our place we took a hike up the mountain and had a picnic, and you were talking about it then.

Kathy: Yes. That was a memorable hike!

Michael: And having spent a lifetime in corporate jobs, I was pretty eager to convince you that you would outgrow this temporary concern. [Laughter]

Kathy: I think you suggested that I watch this movie, Office Space.

Michael: Oh yes, I did.

Kathy: And I did watch it, and it just seemed very foreign to me.

Michael: But it's actually very realistic. It's humorous and a little off the wall but the context of the cubicle was very well portrayed there. And that is a cult classic with people who have lived in the cubicle world.

Kathy: I really have no idea about that world. But on the other hand, I have two friends who recently left the corporate world, one by choice, one not by choice. And they say, "Wow! Working on your own, where do the days go?" They were used to a certain structure, and they got a lot of their personal business of life done on company time.

Michael: Yes, absolutely. That is very true.

Kathy: And I said, "welcome to my world." Also some friends get a little mad at me because I seem to always be so busy and not have time for them. That is because it often takes all the waking hours to get everything done just to keep the studio going.

Peggy: And you don't necessarily have weekends like an 8 to 5 person. If you have to finish for a show, you have to work.

Michael: Are there any particular aspects of your career or adventures that we haven't touched on that you would like to before we finish?

Kathy: When I decided to change my work in 2005 I was trying to figure out ways to diversify what I did in the studio and still survive. One of my first opportunities was an invitation to go to Peru and work in a studio that is in between a factory and a studio. I made a collection of pieces with the help of 30 kind and talented artisans. The whole idea was that they would make these pieces, and sell them to me, and I would market them. It ended up not a great financial venture but in the process, I took these pieces to trade shows and met companies like Crate and Barrel They recognized them as manufactured designs and this led to other opportunities—further trips to Japan and Thailand. I got to visit individual potters and pottery workshops, both small and large enterprises. I love seeing how different people work in clay. We all like the same things. People who work with clay like pottery and they like food. [Laughter] It seems the same everywhere in the world. I really enjoy meeting the people along the way, and staying in touch and breaking bread with them. All connected by clay.

Michael: We have one question we always want to ask, and that is, "What advice would you give to a person who is just starting out? Maybe they are leaving the corporate world, or maybe a young person who has never had a career. At any point in life people get this enlightenment and decide, "I've got to do it!" What would you tell that person from where you sit?

Kathy: I say do it! But do it with your eyes open. Pursue your passion in a reckless way, but also talk to people who are actually doing it, who have blazed trails before you. Pick their brain. Ask them about everything they know. Ask them to teach you. Ask if you can help them in exchange for learning. The combination of passion, determination and seeking mentorship are the most important things I can suggest. Stay flexible. You will have ups and downs. You won't get rewards from anyone else for a while, probably no pats on the back. Encouragement has to come from within. And be ready for a lot of hard work. So if you are up to following your passion, I'd say jump off and dive in. I've never regretted it!

Our monthly radio show: Designing a Creative Life

|

China in two weeks and work with artisans there?" My fist reaction was, "I can't do that now!" But I had a little talk with myself, and figured out how to do it. I got on the plane with very little information except that I was going to be working with some potters who made black pottery. My project was to last for 2 weeks. It ended up not being China at all, but the Tibetan Plateau. 12,000 feet. Everybody in this southwestern part of China is Tibetan. We worked intensely artisan to artisan and of course ate great food together. I had a very rigorous mission to accomplish. This was a collaborative project between Aid to Artisans and the Mountain Institute, and sponsored by USAID. My mission was to train the artisans in better craftsmanship, new designs and marketing. They were too basic to fit into other marketing programs that had been conducted in the region. ATA was looking for someone who was both a designer and an artisan who could work with these potters. It was a great fit. We got so much done in ten days and hoped to work together again.

China in two weeks and work with artisans there?" My fist reaction was, "I can't do that now!" But I had a little talk with myself, and figured out how to do it. I got on the plane with very little information except that I was going to be working with some potters who made black pottery. My project was to last for 2 weeks. It ended up not being China at all, but the Tibetan Plateau. 12,000 feet. Everybody in this southwestern part of China is Tibetan. We worked intensely artisan to artisan and of course ate great food together. I had a very rigorous mission to accomplish. This was a collaborative project between Aid to Artisans and the Mountain Institute, and sponsored by USAID. My mission was to train the artisans in better craftsmanship, new designs and marketing. They were too basic to fit into other marketing programs that had been conducted in the region. ATA was looking for someone who was both a designer and an artisan who could work with these potters. It was a great fit. We got so much done in ten days and hoped to work together again.