The Windhook Interview—Robert Oblon

Bob Oblon is a good friend of ours. We met him throught the Central Coast Sculptors Group at the San Luis Obispo Museum of Art. We hit it off with Bob and his wife, Linda Waldon, as soon as we met. It turns out that we have a lot of common points between us. Both couples met through match.com a dozen years ago, we both have authentic mid-century Heywood-Wakefield furniture, Peggy and Bob both grew up in the greater west Los Angeles area around the same time, and we genuinely and immediately liked each other.

Bob's story is the story of a guy who never strayed too far from his artistic calling, but got sidetracked nonetheless. It is a cautionary tale for those who think that an art related job will keep you fresh and engaged. Art related jobs are great when you can find them, but they are no substitue for doing your own creative work, as Bob will illustrate here.

Michael: Let's start off by talking about your origins—where you started out as a human being.

Robert: I was born in Los Angeles, 1946, Valentines Day. My parents were Russian Jews. My mom was actually born in Philadelphia. The story is that my dad was born on the ship coming over from Kiev. But he really didn't know. I have his documentation when he was naturalized in 1938. He was about 35 years old at the time. They moved out to California right after the Depression. He had been in school studying architecture, and had to drop out of school because of the Depression, and I think he was a traveling salesmen. That's the story I remember. He and my mom came out, and then my mom’s two brothers followed them out. They were pretty young, and fought in World War II. I remember because growing up in the 50s, all the John Wayne movies, and all those World War II things. We had the helmets and the training rifles, and we would run around in the street. But my father’s family stayed back east, so I have relatives in Philadelphia and Maryland today.

This was in the 40s and I have photos of groups like the Inkspots with my sister, who is six years older than me.

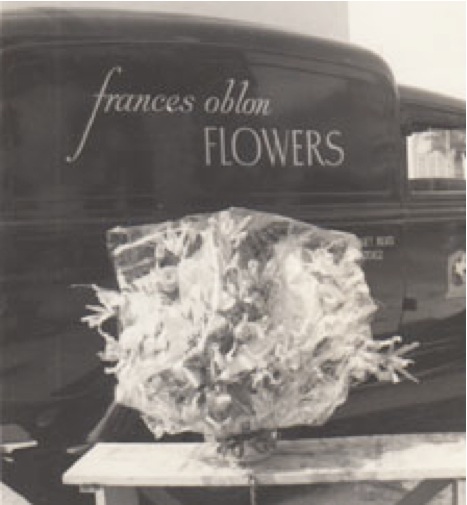

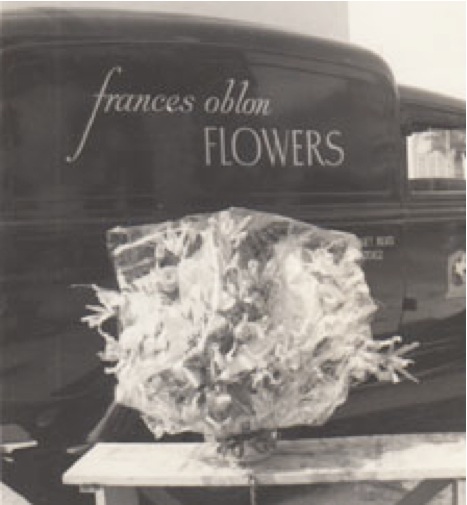

My parents ended up in the flower business in Hollywood.

I guess they did pretty well. The last flower shop they owned, we lived in a house off Vermont Avenue just down from Sunset, so kind of east Hollywood. I went to grammar school there, and the grammar school was on the far side of the flower shop.

When I was old enough to walk home by myself, I would walk to the flower shop, and hang out in the store for an hour or two. During that time, waiting for my mom to take me home, I would make all these little stick and wire and foam objects from all the things they used to make the flower arrangements. I'd use the spray paint to paint these objects, and I'd drip wax on them and unfortunately, I've thought about all of this over the years all of that stuff got chucked into the trash at the end of the day. But thinking back about what I was doing, by today's standards they would be considered kind of minimalist constructions. When I think back to the 50s I was always interested in the arts. And as I got older, by the time I was in junior high school, I found that I had this desire to study architecture. But what I eventually realized was that it was my dad coaching me. I would end up with a book on Frank Lloyd Wright. And I had a drafting table in seventh grade.

Peggy: A dream deferred.

Robert: Well, it was, and very subtly, because my dad was a really stoic eastern European. I'd be sitting in the living room with my parents and my dad would be in his chair and he would say to my mom, "Oh, tell that boy not to do that." It was always the way my father communicated with me – through my mother. I'm sure those early years he was subtly pushing me to do what he didn't get to do.

Peggy: Right.

Robert: So through high school I studied architecture: drafting classes, design classes. And I enjoyed it, did pretty well, and then there was a moment in time where my mom was also saying, "You know, you might want to become a doctor."

Peggy: The typical mother worrying about the...

Robert: Well the typical Jewish middle class upbringing, you know...

Michael: My son the doctor.

Robert: Yeah, so I had thoughts of that for a very short period of time until I started taking chemistry. I like math a lot, but chemistry is just—I think I had really poor study habits, and enjoyed playing around more. With chemistry and biology you couldn't play around. You had to really read the book. And you had to do things right.

Michael: Or else you blow things up. [Laughter]

Robert: Yeah, so that didn't last very long, but I started junior college in the mid 60s really thinking about becoming an architect. I was taking architectural drafting, and rendering, and classes I could transfer to USC, because at the time they had one of the best architectural schools, certainly on the west coast.

Michael: So your dad had unfulfilled aspirations to architecture. Was that as close to art as your family got?

Robert: Right. I remember as a kid, my dad would get up at zero dark thirty, like 3 a.m., to go to the flower market down on Wall Street. I remember a few times, he'd get me up and put me in the truck, and I'd sleep while he drove. We would turn onto Wall Street, and it was as bright as day. That's one of the things I remember. And at 3:30 in the morning, the place was jammed. I mean going! And I'd be holding onto my dad's hand and there were all these people my dad was interacting with. Everybody seemed like they were happy, and it was just a good time. And he would get everything he needed. I know he went several times a week, and then as he got older they started delivering. He dealt with just a hand full of vendors that he worked with for years.

Peggy: Yeah, the guys he knew.

Robert: So yes. I think the flower shop was very creative for my dad as a means of fulfilling some of that desire. And back in the 50s and I think in the early 60s, there was some sort of hair florists ball and the florists would enter this competition. It was a black tie thing, and they'd make these head dresses for models to wear with their gowns. I went to a couple of events, and my dad won a couple of awards. It was around the same time we'd go to Las Vegas with my parents’ friends who were also in the flower business. We'd go see Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack for these dinner shows. And I'd get dressed up in my little suit as a 10-year-old. And my mom had this fur coat, and everyone back then would dress up, and men wore hats. And I remember how my dad would pay the maître d' under the table to get us a good table. It was only when I got older and saw some movies like some of those gangster movies—and my dad wasn't a gangster—but that whole way of taking care of business a certain way, that unfortunately I think, was lost, because that's the stuff I grew up with, and sort of based my relationships on with my friends. Trust and honesty and you know, you say something and you have to live up to it.

Peggy: Your word is good, that's right.

Robert: And I know that's how my parents were. Now it's a badge of honor to have a lawsuit. You never heard of anyone getting sued back then for anything. So it was a really interesting time for me. And in L.A., in Hollywood, it was the beat generation, and I remember in junior high school going with friends and we'd walk up on Hollywood Boulevard, and there was a beatnik place, Cosmos Alley. We'd go there, and we couldn't get in.

Peggy: Right, you're under age.

Robert: Yeah, we're 13 or 14, but we'd listen to these people talking...

Peggy: And the way they'd dress...

Robert: And this whole thing about clapping, and they were reading poetry, and there was jazz. So that was all the stuff—and the car thing. I have boxes of black and white photos of custom cars at a car show in 1958.

I went with a friend of mine, and his older brother who drove us to the car show, and I took all these black and white pictures of all these custom colors but those were the impressions that I've been basing a lot of my color on as an artist.

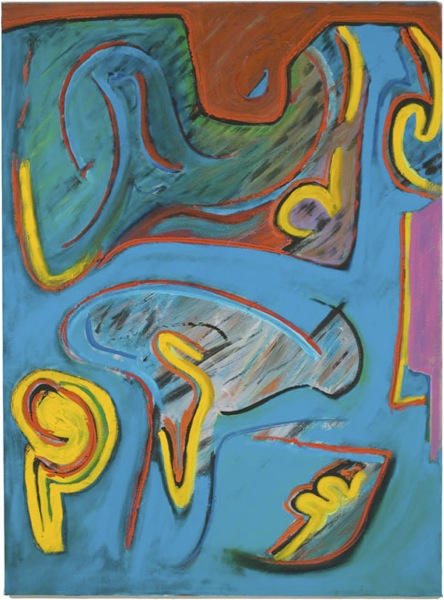

I use a lot of iridescent and metallic colors and they're almost shape shifting. When you walk by in certain light you see some of the changes. And so it seemed like a natural process for me to use all that stuff. It wasn't until I had to do my first artist statement in recent years for a show, that I really put it all together. The way all these influences were the normal everyday thing, growing up in L.A. in the 50s and 60s. Everybody had a car, and if you couldn't afford a paint job, it had to be really clean, and you know, every car you had as a kid was cool.

So that whole influence, subconsciously, that whole finish fetish thing that L.A. artists were doing in the 50's and 60's, through osmosis, long before I was consciously thinking of myself as an artist—you know, it was just the normal stuff that I saw.

Michael: Art reflects culture, and vice versa.

Robert: Absolutely, yeah.

Michael: And you were living in the culture of that art, even though you weren't aware necessarily of the art.

Robert: And I think growing up in a metropolitan area like that, at that time—there are certain times that are special. I had the opportunity to grow up with those things that these movies were made of, not that I had any particular role in that, but it was part of our everyday existence to have a certain attitude, or you knew the guys that had the Camels rolled up in their tee shirts. Or the hot rods. It was that car culture, going to Bob's in Toluca Lake for cruise night. It still gives me chills.

Peggy: What was your first car?

Robert: My first car was my dad's '55 Oldsmobile. I started driving it in '62. I got my driver's license at 16. So his gift to me was the '55 Olds that he bought new in '55, and it was a four door Rocket 98. Cream and grey, and he bought himself a new Cadillac Coupe de Ville, black on black. And my dad, you have to understand this man was so understated, unpretentious. I remember my dad would wash the car, and then he'd get out the Coral Blue, the Cadillac polish. Those visions of him waxing that black Caddy—and you know, I can relate to that, because all my friends were slightly older, and if they had cars, and they were usually these bitchin' paint jobs, and the thing was to polish your car. Just like my dad.

So the Oldsmobile was my first car. From the day I got it until I got hit by a drunk and got rid of it, I drove. Weekdays I'd rush through whatever homework I had, and even if I couldn't get my friends to go cruise with me, I'd just get in the car and drive. The Golden State [Interstate 5] had just opened up, and we lived in the Los Feliz Hills, so I'd drive down Los Feliz Boulevard in the evening, get on the freeway, and at 6 o’clock there was nobody on the freeway. I would just cruise. I'd go out to San Fernando. You know, I'd kind of get lost and work my way back.

Michael: Were you working?

Robert: My first job was working for my parents, hand delivering before I was old enough to drive. Their flower shop was near Kaiser, Cedars before it became Cedar Sinai—it was where the Church of Scientology is — Good Samaritan, and Children’s Hospital, all within four or five blocks. So, of course, I got to know the hospitals really well.

Michael: Tons of flowers going to the hospitals.

Robert: Yeah. And then as soon as I was old enough to drive I made my first delivery to a funeral home, and got to place my first delivery on an open casket, which at 16 was really creepy. But because of that job with my parents, I knew L.A. so well.

Robert: I went to high school in Silver Lake. I had desires of being an architect, and once I started junior college, and started taking design classes, I took a couple of art classes for electives.

Michael: I was going to ask how you made that jump.

Robert: The first art class I had was 2-D design, with Raul de la Soto, who is still a good friend. He's ten years older than I am. So he was in his early thirties.

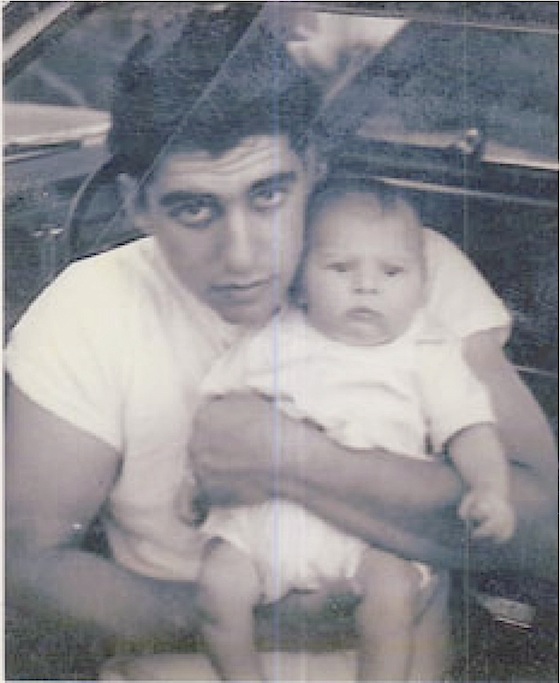

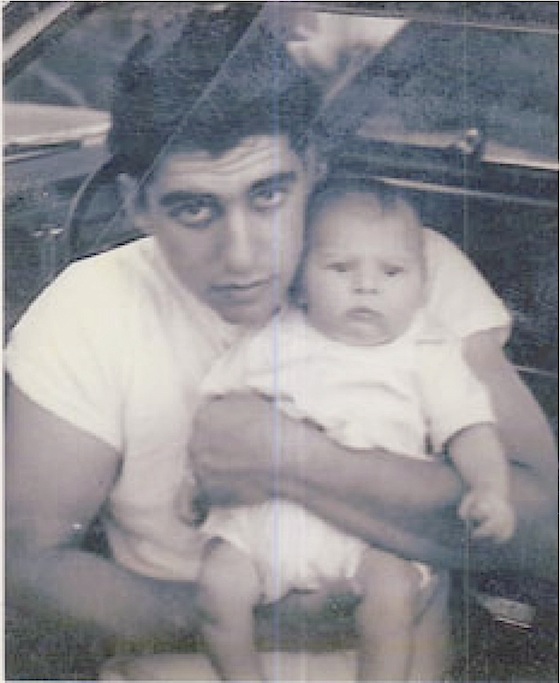

Right out of high school I got my high school sweetheart pregnant and got married, being a stand up guy. I'm thinking, " I'm 19, I can take care of this. I can be a parent. A husband? Sure." But at 19, I thought I was such an adult.

Michael: Don't we all! Yeah, we do.

Robert: So we got married. My son was born that year, so of course, going to college was totally out of the picture.

I worked for a Standard gas station. That's when you had the bow tie, the white outfit and the hat. You cleaned the windows and checked the oil and water, put air in the tires, for $2.25 an hour. And gas was 19 cents.

And then a friend of mine got a job at Albert C. Martin and Associates. Albert C. Martin was the architect who designed City Hall in downtown L.A.—the original City Hall. And he got a job in the mailroom. He used to call me Bobby. So he said, "Hey Bobby, I just got this job and they're looking for..." and I thought, "oh, an architect." So applied, and I got a job in the mailroom. Huge Firm.

Robert: I got to deliver the mail, before I got this promotion, and I remember hanging out in the design department. And I watched the—mostly men, back then. And one of the things I noticed was this whole way they dressed. It wasn't suits. It was slacks and shirts.

Peggy: But nice shirts and nice slacks.

Robert: Yeah. So as I got older I started getting—I never had custom tailored shirts, but you know, it was French cuffs and the slacks with the break a certain way, and it was probably the triple pleats back then. You know, you sit down and they balloon up. [Laughter]

So I went through that phase, and all the guys I knew—You know, Mike Hannon teases me about it. He asks me if I still iron my tee shirts—yeah, I still iron my tee shirts. [Laughter] Certain things haven't died off. I don't iron my Levis anymore. I used to put a little crease on them.

Peggy: But architects wear black a lot. You wear a lot of black.

Robert: I do wear black a lot. So I worked there. Was taking design classes at LACC, and with those first art classes I did really well. It was really easy, and I thought, "Wow, this is fun!"

I started seeing that I was going to work as a draftsman, and that was still the period of time where you had to do like an apprenticeship. As an artist there was still the old way and I think that started to change in the mid seventies with Cal Arts, and some of the other schools where they started having things like minimalism. So I think by that time I realized that I couldn't work for someone. If I were going to become an architect I would have to have my own office. And I was taking more art classes, and enjoying those more, and they were becoming 3-D art classes. And developing form was really exciting, and it was real. It was in the moment. Not some concept on paper that...

Peggy: That might not get built.

Robert: Yeah, and you roll it up and store it somewhere. So here I am at 21, I'm married, a father, my dad had died a couple of years earlier, and I was pretty screwed up. I had this level of responsibility, and all my friends were backpacking across Europe, and into Afghanistan, and bringing all this hashish back, while I was married, and put on 50 pounds, and wasn't having fun. And the art was very pleasurable. It just made sense emotionally. But it was like, "How am I going to make a living?" My mom was still living and when I talked to her about it, she would say, "What are you going to do when you grow up?" She was trying to be supportive, and she was grandma. My sister had gotten married and didn't have any kids, so my son was...

Peggy: …was the focus, right.

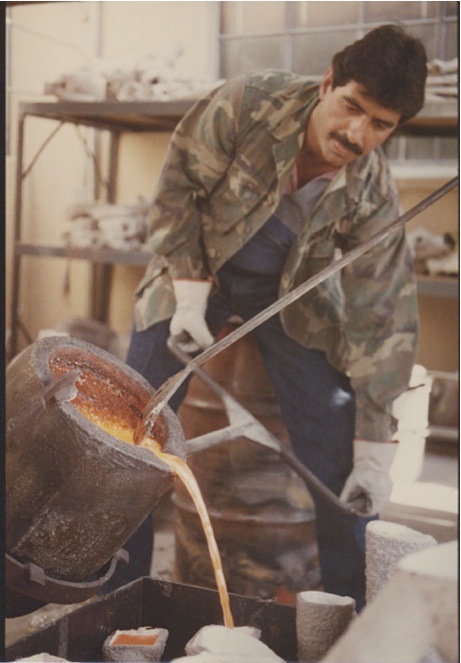

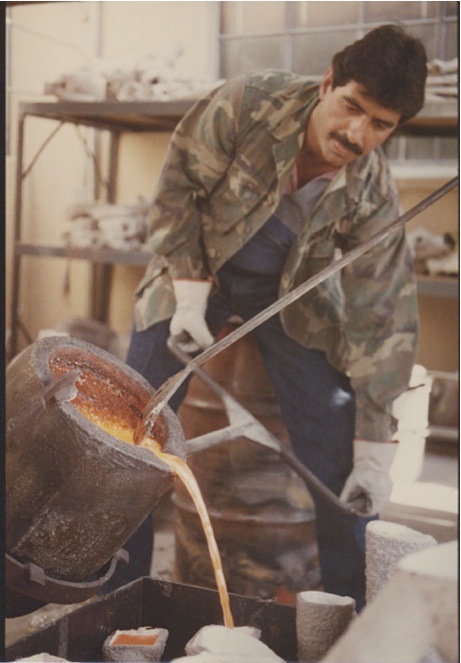

Robert: I wrestled with that for quite a while, and then realized that when I was getting ready to transfer from junior college, I didn't know where to go. Was it going to be USC for architecture? But then I just made this leap of faith, and transferred to Long Beach State because years earlier, having seen those Henry Moore sculptures at LACMA, and buying a couple of books on Henry Moore early on, I thought, "well, I think I want to study art." And I wanted to learn about casting bronze. And Long Beach State had the foundry, and the art department. So I started school at Long Beach State. For me, studying art was all about working.

Peggy: Making stuff.

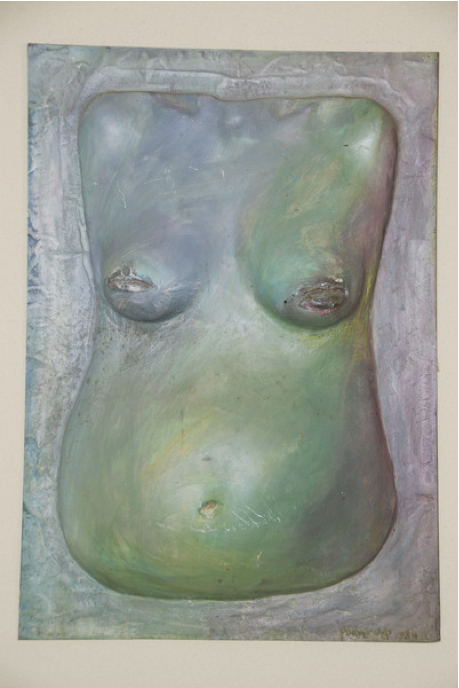

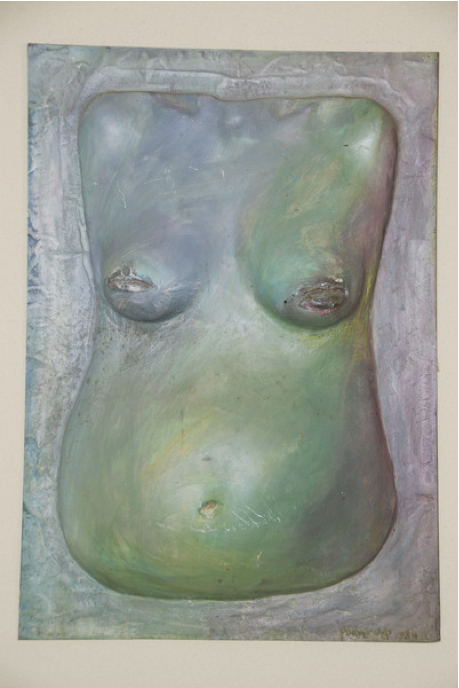

Robert: Working with my hands, and all the work I had done for jobs was some kind of physical labor. And it was always about some process. Even driving jobs. It was going someplace in a truck and off loading materials and documenting it and taking care of the paperwork. With Long Beach State, I took two painting classes, and was told I didn't have a color concept, and stepped away from painting and focused on sculpture. I really fell in love with the molten metal, the human form, and working on metal. Everything worked.

Peggy: It all came together.

Robert: Well, it was this ability to touch the work, and I could work on it and refine it even more, and then through that, started the foundry.

I couldn't afford to go to the couple of art foundries that were in L.A. to get my work cast, and I thought, like I always did, "I'll just build a foundry." You know, how simple is that? It can't be really complicated. I was doing it at school, where we had this foundry setup. So how difficult could that be? Difficult! [Laughter]

It was learning this process beyond taking some classes. I was on the pouring crew every Wednesday, at night. We'd don our regalia, our leathers, and prance around the foundry area, and we'd lift the crucible out and put it into the pouring ring and we could only be the shank guy. You never got to pour. The professors would do that. We didn't get that true glory. But, we got all this attention.

It was learning this process beyond taking some classes. I was on the pouring crew every Wednesday, at night. We'd don our regalia, our leathers, and prance around the foundry area, and we'd lift the crucible out and put it into the pouring ring and we could only be the shank guy. You never got to pour. The professors would do that. We didn't get that true glory. But, we got all this attention.

Peggy: Watching you.

Robert: Yeah. So of course, when I build the first foundry setup in my studio in Long Beach, it wasn't real primitive. But I had no clue what I was doing. I had read some books. The instructors at school hadn't ever built a foundry. The school bought the equipment, and they learned to do solid investment, and that's how I learned. I wanted to learn ceramic shell and the one professor that taught ceramic shell, would not divulge anything—like it was some secret. Which pissed me off. So I started doing research, and found an art foundry in Burbank. The guy became my mentor. He said come out whenever you want, stay as long as you want, bring a pad of paper, ask questions, there are no secrets. That melded really well with how I grew up in L.A. about doing what you say you're going to do, and talking the talk and walking the walk, and all those things that seemed so natural. The foundry part was about learning these procedures, and developing them.

At some point, I became pretty successful with the business, and I started getting calls from artists who were starting out or competitors that had heard about what we were doing. From there it was all about trying to develop the perfect casting. And it was about my desire to conquer this process that should be easy to do. By the time I sold the business I had 40 full time employees, and we were pouring a ton of bronze a day, and because of the growth of the business, I had this great opportunity to develop technical skills that I would get paid really well for.

But I had lost my art. I had lost that physical part because the business took precedent. It was a great, viable business, and I was working with some really important people in the art world. I don't think I was caught up in the personalities, but I was caught up in the process. It's the closest to alchemy that one can come without actually transmuting base metal to gold. And as many tons of bronze we poured daily for years, it never got old. It was always exciting.

Michael: There's something magical about it.

Robert: It's so magical! I get goose bumps now just talking about it, and if I have an opportunity—glassblowing is the most recent thing I've been very slightly involved in, and some raku recently too. Well, it's that heat. It's the noise. It's the thrill, like no drug that I ever took. [laughter]

Robert: That was part of the magic, because it was like Christmas every day. And I'm the Rabbi, the priest, the counselor, the therapist, the ‘you name it’, and I was the...

Peggy: Getting the jobs.

Robert: I was selling, and I was the collector, and I was throwing clients out of my foundry that wouldn't pay me or were a nuisance. Getting invited to all these A-list parties. It was really exciting, but it was work. It was part of the deal. I probably could have taken it even further, but I got to a point where I hated it. I loved the process. We had a big tilt furnace that would melt 1200 pounds at a time, and there was nothing more exciting than being in that area at that time, because everything would rumble. You know, the noise, and the heat, and pulling the molds out of the holding kilns, and you know I had done that and had seen it almost every day for almost 20 years, and I never lost that. But emotionally I was so detached from being creative. Technically I was very skilled. But creatively I was dying.

Peggy: Because having that business you weren't doing your own work at all.

Robert: I had every opportunity, but I was so consumed by the business. I had one crew 8:00 to 4:30, I'd be there at 7 to open up and figure out what we were going to do, and then when they would leave I would stay. If there was a job to push through, I'd be in the dip room. I had three guys in the dip room with two slurry barrels dipping 400 shells a day, and I'd go in there and concentrate and I'd get an extra two dips maybe, or I'd sit at the welding table for several hours. I'd do all the refined silver brazing, or if it was a custom job, then I would do all the work. I'd do the wax. I'd do the chasing, the pouring maybe. If it was really important I'd probably pour the metal. All the finishing. The patinas. I made all the rubber molds. We had a guy that did rubber molds all day. As long as I worked physically, I think my sanity was ok. But as the business started operating on its own, I would show up and wanted them to know I was there, that's when I became more cognizant of how I was starving for creativity. I was successful, and I earned it, but it was boring. It was empty. More money, but the money never really had any value. It bought some toys. That was it. So I was becoming really unhappy.

Michael: How did you resolve this dilemma?

Robert: I had an opportunity to sell the business, and unfortunately didn't get my money. I had to sue the people to get my money and it took five years. So that time period was a lot of suffering financially, emotionally, because my baby that I had built from nothing to this really prominent thing had been taken away from me. I was willing to give it away for the price agreed upon, and walk away, but now that had been taken away. Anyway, my mom died, my best friend died, I injured my back, and I got divorced, all within a year and a half.

That's when I moved up to the Bay area. I needed to get out of L.A. I was 45 and I had to go back to work. I was pretty angry and bitter. I weathered the storm, had my two weeks in court, won, the guy threatened to go bankrupt, so I had to cut a deal, and then offered to buy my ex-wife out of the house, and she didn't want that, so I gave her money. I was just fried.

I moved to San Jose, had a friend there, and thought about going back into the foundry business, but it had become so expensive and I didn't really want to be back in the business. Then, Linda and I met. It was 2001 when I almost died from an infection and on the flip side of that, I started painting.

I was totally whacked out and needed to do something.

When we bought this place in Arroyo Grande, Linda was already tired of hearing me complain about, "I'm really an artist. Look at all the stuff I made years ago."

And basically she said shut the fuck up. [laughter]

I was totally whacked out and needed to do something.

When we bought this place in Arroyo Grande, Linda was already tired of hearing me complain about, "I'm really an artist. Look at all the stuff I made years ago."

And basically she said shut the fuck up. [laughter]

Peggy: "Go do art."

Robert: Well, build the studio, and shut up! So we built the studio and then I was thinking, "Now what do I do? Now I can't complain anymore." At the time when I built the studio, I was going to build a foundry.

I was going to size it down to what I had when I was living on 10th Street in Long Beach in the 70s. My friend, Mike Hannon, and I would pour once a week, and it was a big, fun thing, and we'd invite people over. It was a party.

So here I am pushing 60 by this time, and in good shape, but having had this hiatus of nearly a quarter of a century, the fantasy of doing all this physical work just because I saw myself as a sculptor started to fade. I didn't even know what I was going to do with my work. Is it going to be this figurative stuff that I'd been doing all those years? Physically I could do it but it didn't really resonate with me any longer. So I was walking around in the studio one day. I didn't have doors or electrical power. I had the drop cord so I could run a tool or light the studio. One day I was talking with my painter friend, Lynn Coleman, from L.A., who had posed for me through two pregnancies when I did this whole series of body casts in bronze. She said, "Well, don't you have some old scrap wood or something? You can just do an assemblage."

She was tired of hearing me whine, too. So I put this thing together, and I painted it, and I thought, "Wow, this is kind of fun." I brought it in the house, and Linda fell in love with it.

Linda’s friend, Kory, was visiting, and she had just opened a gallery in San Francisco. She fell in love with the piece, and she said, "Do you want a show?" I said, "Sure!" That was February of '06, I think. She said, "How about April?" Remember, this was February, and I said, "OK." I had no work.

Linda’s friend, Kory, was visiting, and she had just opened a gallery in San Francisco. She fell in love with the piece, and she said, "Do you want a show?" I said, "Sure!" That was February of '06, I think. She said, "How about April?" Remember, this was February, and I said, "OK." I had no work.

Peggy: You had one painting.

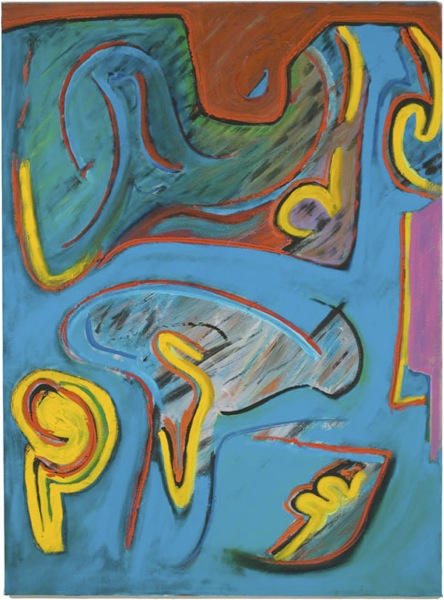

Robert: I had an assemblage, and I got lucky. I had no clue. I knew that I didn't want to paint on canvas. They're fun, but I knew that I needed to work three dimensionally. I had gotten a big piece of equipment, and it came in a big crate, and I kept the plywood. So I started cutting these shapes out of plywood, and putting them together, and I had no clue what I was doing. So I'm scurrying around, and March came and I had two pieces. I wasn't sure about the paint, because in the back of my mind I'm still hearing that professor in that painting class saying, "You don't know anything about color." Or whatever she said.

Peggy: You said she said you had no color sense.

Robert: So whatever I was doing, I was thinking, "I don't know what I'm doing."

I'd have Linda come down and look at it, and she'd say, “I love it! Keep going!” And of course I didn't believe her, because, you know, she loves me, so anything I do is great. So I'm doing these huge things because I need to work large, because everything I like in galleries is large. So how difficult can that be? I have a little tube of paint, I have a little paintbrush, and I squeeze it out, and I'm half way done with a painting, and $300 worth of paint later, I'm thinking, "This is crazy."

So I called Kory, the woman who had the San Francisco gallery, and I said, "I'm not going to be ready for the show in April. Is there anything later in the year?" "Well, what about August. I think there might be a cancellation." I said, "Perfect! August." You know, it's so much more time. So I called Mike Hannon, and I told him what I'm doing and I asked him to help. We built some movable walls to work on. Then I would draw on plywood and Mike would come over and he'd help cut, and we had this routine going. I think I did seven or eight really large pieces for the show. I was doing these paintings, and trying to make them sculptures, and yet knowing I wanted them to hang on the wall. So the show came together. We included some of the bronzes from twenty years earlier to fill the gallery. I was walking around the show thinking, "Oh, I've really got my shit together."

When the show was over I went into a funk. Now what do I do?

I started applying to juried shows, and getting rejected, and I kept painting. For me it's been six years trying to catch up on what I feel I may have lost out on in the 25 years that I wasn't doing anything. And realizing that I can't just fantasize about it anymore. If I'm going to take myself seriously as an artist, I'm going to have to just keep working.

I don't think I ever gave up the work ethic, because with my swimming pool business, it was certainly about physical work and selling and closing the deal and then making it happen. You know, a re-invention of the foundry on a different scale. As I continued to work, I got invited to a group show with some figurative painters, and it just kept reinforcing my work. It’s about follow-through and continuing to do the work, and believing in what you do. It's becoming skilled with your materials. I think that's ongoing. Every day I'm in the studio, I'm always learning something. How I apply the paint, how the layers of paint work together, how the colors affect what's on top, what's below it, what's next to it.

And, getting involved with the community. I think that's been really important, not just to take from the community, but to participate. So now the work has evolved from the early assemblage that I still think is great, to these pieces that are becoming a bit more minimal. Developing the color in a certain way that I think works as my language. In the earlier pieces I was being influenced by certain artists whom I admire. I think that's what everybody does early on.

When the show was over I went into a funk. Now what do I do?

I started applying to juried shows, and getting rejected, and I kept painting. For me it's been six years trying to catch up on what I feel I may have lost out on in the 25 years that I wasn't doing anything. And realizing that I can't just fantasize about it anymore. If I'm going to take myself seriously as an artist, I'm going to have to just keep working.

I don't think I ever gave up the work ethic, because with my swimming pool business, it was certainly about physical work and selling and closing the deal and then making it happen. You know, a re-invention of the foundry on a different scale. As I continued to work, I got invited to a group show with some figurative painters, and it just kept reinforcing my work. It’s about follow-through and continuing to do the work, and believing in what you do. It's becoming skilled with your materials. I think that's ongoing. Every day I'm in the studio, I'm always learning something. How I apply the paint, how the layers of paint work together, how the colors affect what's on top, what's below it, what's next to it.

And, getting involved with the community. I think that's been really important, not just to take from the community, but to participate. So now the work has evolved from the early assemblage that I still think is great, to these pieces that are becoming a bit more minimal. Developing the color in a certain way that I think works as my language. In the earlier pieces I was being influenced by certain artists whom I admire. I think that's what everybody does early on.

Michael: Who are some of those people?

Robert: Frank Stella, Elisabeth Murray, and, probably for work ethic, someone I know personally, Chuck Arnoldi. I've been influenced by Robert Rauschenberg and that school of abstract expressionists. I don't think of myself as an abstract expressionist. My work is abstract but it falls into several categories. Because I'm cutting these shapes there's a figurative element that plays, where you can see body parts there. It's undeniable. It's how I was trained. That's what I grew up with as a sculptor. Contemporary artists like Jackson Pollack and De Kooning influence me. Probably the most current work that I really enjoy is Gerhardt Richter. The way he moves those monumental slabs of paint across the surface is amazing.

Michael: What is your creative process?

Robert: I've tried to do sketches for my preliminary work. I’ll work on a series of paintings, and I get to a point where I'm bored, so I change the application of paint, and then I find something that I'm in love with for a while, and I move in that direction.

Two years ago, I felt like, "Well, I don't know what I'm doing." And I was serious. I had no fucking clue what I was doing then. But then I'd sleep on it, and sometimes with certain pieces, I'd come back in the morning and peer through the doors and I'd go, "Wow, this is pretty cool." So that's taught me that I do know what I'm doing. It's taken five or six years to feel, not cocky, but pretty comfortable with the material.

And jumping to oil right now is putting myself out of my comfort zone purposely, to see if I can get similar results in the way that oil does its own little magic. Because it's all magic. We have the luxury as artists to be able to take a material and turn it into something that other people will look at, and whether they like it or not, they are intrigued. I've always felt that my job is just to do the work.

I used to be concerned about what other people were doing. That has nothing to do with me. Only in the big picture does it have some significance but it's more about whether my art is relevant in this moment. It’s relevant to me. I'm not Gerhard Richter, I'm not Elisabeth Murray, I'm not Frank Stella. They're great artists. My greatness is not what I'm doing now, it’s what's to come. So that's part of the excitement that keeps me motivated.

The times when I'm not in the studio, even if it's a day or two, that's when the craziness sets in. I think we're all that way.

It's not just joy, because it's not always joyful. I'm in there stomping around sometimes. How do I make this happen? And I know every time that the only way I'm going to make it happen is to get the paint out and move it around the surface. And it all comes through doing the work. It doesn't come through sitting in here asking, "How does this work?" I know how it works when I'm out there.

Michael: I think a lot of people struggle with the difference between working and thinking about working. Personally I have a lot of experience with this. You've got ideas in your head. You think about things you could do, but nothing really gets done there. But when you get in and start to work, that's when all of the progress happens.

Robert: Yeah, and sometimes you have to think about what to do to refine the process a little more, and yet it's not until you touch the paint to the canvas or your fingers to the clay, or whatever your materials are, that it sparks real progress.

Michael: I've never understood how those people work who can design their work in advance. I've never been able to do that.

Robert: I don't either, but I think somewhere in the mind, all that is in there. I have had dreams, especially in the foundry days, where I would work through a problem in the dream, and then the next day I would go into the foundry and I would take that idea and it would work.

So everything in between is chance and luck and work, hard work. I don't know of any other way to get there. And with my hiatus for a quarter of a century I fantasize a lot about how I can get there, how I should be there, how I should be getting there and who do I know and who I've known.

Michael: I've been there. I've spent that quarter century. It was forty years for me.

Robert: I think some people that I've had an opportunity to meet; some of them never lost sight of the goal, the dream, whatever you want to call it. For someone like me and maybe for you, I got sidetracked not just by life—because we all had a life—but I meandered around too much and I was maybe looking for those things in other people and other places thinking they were going to solve the mystery. Well there is no fucking mystery. It's just you either get in and do it or shut the fuck up.

Michael: What would you say to someone who is just starting out? In other words, if I had to do it over again here's what I want you to understand.

Robert: Trust who you are. Don't be afraid of work. Know that it's rare that it happens overnight so don't be scared to work, don't be scared to be by yourself in your mind, and don't worry about other people say because we're all the same. So work hard, work diligently, don't take no for an answer and don't believe when somebody tells you that you don't have any color sense.

|

It was learning this process beyond taking some classes. I was on the pouring crew every Wednesday, at night. We'd don our regalia, our leathers, and prance around the foundry area, and we'd lift the crucible out and put it into the pouring ring and we could only be the shank guy. You never got to pour. The professors would do that. We didn't get that true glory. But, we got all this attention.

It was learning this process beyond taking some classes. I was on the pouring crew every Wednesday, at night. We'd don our regalia, our leathers, and prance around the foundry area, and we'd lift the crucible out and put it into the pouring ring and we could only be the shank guy. You never got to pour. The professors would do that. We didn't get that true glory. But, we got all this attention.

I was totally whacked out and needed to do something.

When we bought this place in Arroyo Grande, Linda was already tired of hearing me complain about, "I'm really an artist. Look at all the stuff I made years ago."

And basically she said shut the fuck up. [laughter]

I was totally whacked out and needed to do something.

When we bought this place in Arroyo Grande, Linda was already tired of hearing me complain about, "I'm really an artist. Look at all the stuff I made years ago."

And basically she said shut the fuck up. [laughter]

Linda’s friend, Kory, was visiting, and she had just opened a gallery in San Francisco. She fell in love with the piece, and she said, "Do you want a show?" I said, "Sure!" That was February of '06, I think. She said, "How about April?" Remember, this was February, and I said, "OK." I had no work.

Linda’s friend, Kory, was visiting, and she had just opened a gallery in San Francisco. She fell in love with the piece, and she said, "Do you want a show?" I said, "Sure!" That was February of '06, I think. She said, "How about April?" Remember, this was February, and I said, "OK." I had no work.

When the show was over I went into a funk. Now what do I do?

I started applying to juried shows, and getting rejected, and I kept painting. For me it's been six years trying to catch up on what I feel I may have lost out on in the 25 years that I wasn't doing anything. And realizing that I can't just fantasize about it anymore. If I'm going to take myself seriously as an artist, I'm going to have to just keep working.

I don't think I ever gave up the work ethic, because with my swimming pool business, it was certainly about physical work and selling and closing the deal and then making it happen. You know, a re-invention of the foundry on a different scale. As I continued to work, I got invited to a group show with some figurative painters, and it just kept reinforcing my work. It’s about follow-through and continuing to do the work, and believing in what you do. It's becoming skilled with your materials. I think that's ongoing. Every day I'm in the studio, I'm always learning something. How I apply the paint, how the layers of paint work together, how the colors affect what's on top, what's below it, what's next to it.

And, getting involved with the community. I think that's been really important, not just to take from the community, but to participate. So now the work has evolved from the early assemblage that I still think is great, to these pieces that are becoming a bit more minimal. Developing the color in a certain way that I think works as my language. In the earlier pieces I was being influenced by certain artists whom I admire. I think that's what everybody does early on.

When the show was over I went into a funk. Now what do I do?

I started applying to juried shows, and getting rejected, and I kept painting. For me it's been six years trying to catch up on what I feel I may have lost out on in the 25 years that I wasn't doing anything. And realizing that I can't just fantasize about it anymore. If I'm going to take myself seriously as an artist, I'm going to have to just keep working.

I don't think I ever gave up the work ethic, because with my swimming pool business, it was certainly about physical work and selling and closing the deal and then making it happen. You know, a re-invention of the foundry on a different scale. As I continued to work, I got invited to a group show with some figurative painters, and it just kept reinforcing my work. It’s about follow-through and continuing to do the work, and believing in what you do. It's becoming skilled with your materials. I think that's ongoing. Every day I'm in the studio, I'm always learning something. How I apply the paint, how the layers of paint work together, how the colors affect what's on top, what's below it, what's next to it.

And, getting involved with the community. I think that's been really important, not just to take from the community, but to participate. So now the work has evolved from the early assemblage that I still think is great, to these pieces that are becoming a bit more minimal. Developing the color in a certain way that I think works as my language. In the earlier pieces I was being influenced by certain artists whom I admire. I think that's what everybody does early on.