Leslie and Mike Hannon are artists living and working in the south part of San Luis Obispo County. Their story is a lot of fun, and a classic case for Outside the Lines. You will read here about a couple who has skillfully interwoven work and creativity at every turn throughout their lives. And Mike has a San Luis Obispo Museum of Art show coming up with David Limrite too.

Peggy: This is different because we haven't really interviewed a couple who are both artists. So this is new and one of the things we usually ask first is when did you know you wanted to do art? You go first, Leslie.

Leslie: I have an aunt who is an artist and I knew I wanted to be an artist because she was. And I felt it inside me that I could do this, that I must do this, that it would be part of my life. Also, my grandmother sewed. I watched her often and learned a lot from her, including embroidery and knitting. Later, starting in the eighth grade, I took home making, which included sewing. Unfortunately, or fortunately, I had to wear the clothes I made. I took my babysitting money down to the Newberry's to buy the cloth, bring it home, and sew my fashion statements. This continued throughout high school.

Peggy: And so as a child what kinds of things did you do?

Leslie: I did drawings and paintings. I didn't have a lot of materials to use but I've just always used my hands. We were given things like blocks as toys, building blocks, nothing really with moving parts so we would just build things. And in the backyard Mom would give us sheets, anything she had, and we built tents and we would live in them in the backyard. I just was always using my hands.

Peggy: And where was that?

Leslie: That was in Lennox, CA. We lived near LAX, under the flight path. The good part about that was that as kids, we could cross over Anza and go into the industrial area of quonset huts and dumpster-dive behind Mattel toys and Rose Marie Reed swimsuit manufacturers. We would bring home our treasures, and make our own toys out of broken parts or doll clothes out of swim suit material.

In 1955 and 56, my family lived in Japan. My father worked for North American Aviation helping Mitsubishi make F86 fighter jets. We lived in Nagoya. There were about 20 other families in our village. We lived out in the country and rode a bus into the city to an American school. My dad bought a Nikon camera. He took color slides everywhere we went. I did not think of it at the time, but much later, I could see that he really had an artist's eye for composition. He loved the people, and took extremely compassionate pictures of a war-torn country. It was only about 10 years after WWII.

National Geographic would have liked to have seen those photographs. I recognized cultural differences between American styles and Japanese styles early in life. I believe there is always a little Japanese influence in the work I do based on my experiences as a child in Japan. There is a certain kind of editing that's hard to explain that's deeply engrained from childhood.

When we came back from Japan, it was not long before the 405 freeway was built across the street from our house. We moved to Palos Verdes.

Peggy: Mike when did you get hit by the art bug?

Mike: I got hit by the art bug early on. My mother would keep me entertained if I was bored. She would give me some paper and colored pencils and challenge me to draw something. So I did that early on and I always enjoyed doing that. And I took ceramics classes and a sculpture class in junior college and had a really good instructor who inspired me. That happens a lot. When people are inspired by somebody and they're good at what they're doing, they go on. I went on to college and I was a business major and it didn't take me very long to figure out that that's what I didn't want to do. I wanted to go in the direction of teaching art, because I always thought that there had to be a way to make a living—and teachers, boy they've got it made! That's the best. And so first I thought I would be a ceramics instructor.

After I graduated with my business degree, I took a job with Shell Oil as a company rep. I did that for about six months and figured out that I didn't want to wear a coat and tie every day.

I got drafted. My Army job was at the craft shop at Fort Ord. I arrived at the craft shop thinking that I would get into the ceramics department there. This was a huge art department at the craft shop. It was like the showcase for all the Army and the Army was huge at that time. It was the middle of the Vietnam War. They didn't need a ceramics instructor and they said, "Our jewelry and lapidary instructor is leaving in three days so you'll be the instructor." So I had three days instruction on how to do wax and invest and cast and cut and polish stones and that's what I did in the Army. They didn't want me to wear a uniform. They wanted the troops, when they came in, to relax and feel comfortable. So that's what I did. And while I was in there I thought this was a good direction, jewelry and metalsmithing. I liked working with metal. And I looked around and did a little research and found out that Long Beach State had a really good jewelry program. So I went down there. Applied and got in, and metalsmithing was part of it. It was the first time I had done that. So that's how I got into metal. As far as being an artist, I don't know that I really ever thought I would be an artist until we moved up here. Bob (Robert Oblon) and Leslie started doing art, because we've worked all our lives and they finally convinced me to start and that was the beginning. That was up here maybe three and a half or four years ago.

Michael: Wow. You once told me that you were kind of a military brat. You wandered around the country with your military parents. Talk a little bit about that.

Mike: People always ask me where I'm from. I was born in Omaha, Nebraska but I was only there for six weeks. We moved around the country, we moved to Bogota, Colombia in 1952 and were there till 1955. Then we moved to Montgomery, Alabama, which was kind of like a foreign country in itself. I was in Alabama for five years and from there went to Germany and lived at Rhein-Main for two years.

Peggy: Was your Father Air Force?

Mike: Yes, Air Force. So we were at Rhein-Main for two years, which is where Frankfurt is and I went to school at Rhein-Main and Frankfurt. Then we moved to Ramstein which is in the southern part of Germany for two years and from there we moved to California. My Dad retired so we've been in California ever since 1964. So that was the Air Force life. No permanent home.

Peggy: Going back to the craft shop—the Army personnel were coming through there for a short period of time and you were teaching them for recreation? Or who were you teaching?

Mike: Well Fort Ord was a big training base for soldiers going to Vietnam. So they wanted a big craft shop. They wanted someplace where these people could unwind. Also they came back from Vietnam and they came back to Fort Ord and they wanted them to have a place where they could go that wasn't an Army experience so much. It was the soldiers, it was their wives and their sons and daughters. And I worked from 1:00PM till 10:00PM at night. Had Monday and Tuesday off and it was a great experience. I loved it, got full military benefits. They ended the war and I got an "early out," so I only served eighteen months and one day.

Michael: So from there you went to Cal State Long Beach, and I think there's going to be a lot to talk about on that, but I wanted to jump back over to Leslie for a minute. I think you met Mike at Cal State Long Beach, right? So how did you get there, Leslie?

Leslie: I went to junior college and got an AA in Art and I couldn't get into Long Beach State because it was during the Vietnam War, and it was quite full. So I had a bit of time before I could go. I heard that they had a textile department there and I was kind of interested in that—in weaving. My parents lived in Arizona, by Sedona at the time and so I went there and took weaving from a lady. I lived in a trailer and every day I would go to Sedona and weave in her studio. Her name was Ada Rominger. She taught me how to weave at the beginning and then time passed and I was able to get into Long Beach State. So I got into a textile department there and I kind of put the drawing and painting back on the back burner a little bit. I don't even know why I wanted to learn how to weave, but I did. Turned out it was a good thing ultimately. So I got a Masters Degree in textile design, which is not really a well known degree, I haven't really had any use for it per se, except that it segued into a trim business.

Michael: So I'm not sure which direction to go from here, there are branches at this point.

Peggy: We won't forget the segue to the trim business, but maybe for the sake of history, we can talk about how you two met, which I believe was at Long Beach State.

Leslie: Well my friend Vicki and I were in the textile department together and then we got an apartment together. We had looms in the living room but we decided we needed a studio space and Bob Oblon was managing a complex of artists studios in storefronts in Long Beach. Mike was in one and there was one that had just become vacant. Our friend Tom Finerty was going to go to Chicago to the Art Institute, so his space was open. We moved our looms in there and at the time I was doing some very large sculptural pieces out of sisal cable that we got down at the docks in Long Beach. I was sitting on a pile of these ropes with the door open waiting for the gas man. And the first I see of Mike, he sees me in there, and he says, "Hi. What are you doing?" I said, "I'm waiting for the gas man," and he goes, "Oh no, no, no, no gas man." And I said, "But we need the gas turned on," and I don't remember how we got the gas turned on but that's how we met.

Peggy: Why no gas man?

Michael: I want to hear your side of this story Mike.

Mike: Well it's pretty much that. but we were living in these storefronts and we weren't supposed to be. These were stores. This was not a living area. So we had to constantly be on the lookout for city inspectors of one sort or another. Electric, plumbing—the gas wasn't so bad, but it's like you didn't want to sit there with the door open and have somebody looking in. So we finally figured it out. The gas man knocked and we made sure it was the gas man. We let him in and he got the gas going. We lived like that, it was kind of in secret for three years.

Leslie: It was wonderful.

Mike: $65 a month rent.

Peggy: So how many artists, or how many studios were in this complex?

Mike: Well there was Robert Oblon, he had Sun Foundry, his bronze foundry, we set that up. I was next to him. There was Tom Finerty next to me initially and then Leslie and Vicki. And then on the other side of that was Vic Smith and Kay Yee.

Leslie: There was a scupltress. I don't remember her name.

Mike: She was later. Kay Yee was a jeweler and Vic Smith was a sculptor. And the landlord's son lived in the far unit. We had a dirt lot behind all these storefronts and we built a huge fence around it. Bob built his foundry back there and we had some ceramics guys that built their kilns and they had a ceramic business going back there. And I had a jewelry studio set up and Leslie and Vicki had a weaving studio. It was just a little clandestine artists' colony. It was really fun and we had a great time there.

Michael: So that was about three years?

Mike: Yes, about three years.

Michael: About what time was it when you guys met and had this artist colony going in the storefronts?

Leslie: The early '70s, he lived there before I did.

Mike: Probably '74 or '75, somewhere in there.

Leslie: No, '73 also.

Mike: Yeah, we try to figure it out but we don't know.

Leslie: We do this all the time.

Peggy: So when did you get married?

Mike: We got married in '78, we know that.

Leslie: At least we know that part. It's the when-we-first-got-together part that we can't remember. It's all kind of fuzzy.

Mike: Well what happened was the building with all the art studios in it got sold so everybody started moving out. So Leslie and I were going, "Well ok, what are we going to do? Maybe we should buy a house, let's buy a house." So I had the G.I. Bill and she had a $1,000 and Bob vouched for me that I was his foundry foreman and made all sorts of money and so we bought our first house. We painted it inside and out, sold it and made $10,000 and starting looking for a house to actually live in together. And downtown Long Beach, which was the original Long Beach with the old houses, real old beautiful places. We found a two-story Victorian built in 1906 with four garages in the back and an apartment over one. We bought that and we got married at that time. We thought at that point the finances were getting too complicated, that we might as well get married.

Leslie: He owed me too much money, that's what the complication was. (laughter all around)

Peggy: So how did you make a living at that point?

Leslie: Ohhhhh, yes. I was a CETA Artist-in-Residence at that time through the Parks and Recreation Department of Long Beach. It was during the Carter Administration, and so I always thank him for the job. I was able to save money because the rent was cheap, and we lived very frugally. That was how we started really.

Mike: When Leslie and I first got together I had a wholesale jewelry business going. It was kind of the Indian silver, turquoise, some scrimshaw, and ivory, which was legal at that time. It was a wholesale business and we had rented a building. We had six people working for us and we were selling jewelry wholesale around the country. And we did that for about two years and the market just crashed, at that time there was a downturn, silver took a dive and then disco came and everybody was wearing gold chains. Nobody was buying silver. So there went the business!

Peggy: Oh dear! [More laughter all around]

Mike: So I'm thinking this is getting away from me, I thought this business was going to work and so I thought I need a job, I need a way to make money, I need a trade. So I went to this occupational school at the LA Harbor and I learned welding and did their sheet metal class also. And because I was in the metal smithing class at Long Beach State I knew how to move metal with hammers and to solder and put things together. But this was a new way of working with sheetmetal, working with tools and machines that crimp metal and bend it and make different ways of putting it together. And I did welding at LA and Long Beach Harbor, welding on boats. This was when Leslie and I were first getting together and I did that for probably a year and a half and then her friend Vicki was working at the Toyota Design Center, which is called Calty. She said, "You know, they're building a new building in Newport Beach and they're going to need some people." She got me an interview and I interviewed and I got hired by Toyota. And it's kind of all the things that I'd been doing, the jewelry, the metalsmithing, the welding, the sheet metal, all came together—and the art. I had a little portfolio and they liked what I had to offer. So that was my career with Toyota for 25 years.

Michael: We sat with you at dinner with some friends of yours who were also at Calty and you guys told some amazing stories of the creativity of that place. I'd like to hear some of that again.

Mike: Well it was an amazing place. All the designers when I first got there, for probably the first five or six years, they were all from Detroit. They were from Ford, GM, Chrysler, and they were kind of like every other designer in the country. There wasn't anything different. They were designing the same style cars and then we got the head of the company from Japan. His name was Katsuo Nosho and this guy was amazing. He was a philosopher, he was a thinker, he was very enlightened. He was an origami master who was published in books and world famous.

And he had a different approach to doing design. He kind of took that company and shook it. And the main thing he told us that really got people going creative wise was he said, "I want you to fail. I want you to make mistakes. If you're not making mistakes, I'm not happy." This is his introduction speech to us. He's brand new, and everybody's sitting there looking at each other going, "Is this guy nuts or what?" I mean it was something really different. And he shook things up. The first thing he did in that speech was so different. If you can picture a corporate CEO talking to this group and he's new to this company and he's taking over, and he's telling everybody who he is, and he reached into his pocket and pulled out of his jacket a little origami heart. And he said, "Please, don't break my heart." And people's jaws dropped and we're going, "Is this guy insane? What is this going to be like?"

Michael: So then what was it like?

Mike: It was incredible. It was so creative. We had down time. We would work all year and then we'd ship the models in November. We would have about a six or eight week period where it was just overtime, just crash to get all these design models ready to ship to Japan. And then they'd ship and it was just like somebody let the air out of the balloon, everybody just sank. And for the next three months it was kind of a down time. You'd just look for something to do. And he'd say, "Okay, we're going to do an art project. I want everybody in the company, including secretaries to do an art project. You have a budget. You can do anything you want. You can take art classes in Laguna, you can do anything, anything goes. And for the next two months we were on our own. People were coming and going, and I tell you the excitement level at the place—it made a difference. People just got pumped with energy and creativity and it transferred to design. There were some real important designs that came out at that time and Calty sort of was leading the world I think in car design for awhile there. And we had several designs that went into production, it was really an exciting time.

Michael: I remember a story about water balloons?

Mike: One of the designers got some balloons, the long narrow ones, and he filled them with wet plaster that he would take and squeeze and twist and pull those things and then he would stack them together, then take photographs. Then he would look at those and he came up with the design for the first Lexus SC 400. That was his design, that was a very successful Lexus, the very first one, and it was based on this balloon thing that he was doing with wet plaster, and that came from his art project that Nosho had us doing. I saw it in the news. There were TV shows, there were interviews, it was a pretty famous event in car design.

Michael: I'm drawing all this from the conversation I heard a few months ago that I heard at dinner. But I think you mentioned something about life drawing classes or something?

Mike: Oh, and that was another thing. We got a live nude model in there and all the designers in one room and a nude model and they drew this model for three days. And car designs came out based on what they were doing in this class. It was pretty exciting too. Nosho just kept coming up with these things to stimulate us and it really worked.

Michael: This is really rare in the corporate world.

Mike: It is, it's very rare. And he was quite a strong personality in that he wouldn't let people from corporate Toyota come and visit us. He kept them out. He just said, "No, you're not coming in. If you're happy with our designs, good." Because Detroit and the car industry is famous for interference from different department heads. Everybody comes in and they want to put their thumbprint on a model, "Oh change this." "Can you change that?" and he wouldn't let anybody come in. He wasn't popular with a lot of people over there, but the top people, the Chairman of the Board and the Directors liked that. But down below they weren't so happy with it. But you know, it was that kind of thing where we had all this creativity and it was just this little bubble.

Peggy: How big was Calty at that point? How many people were there?

Mike: At that time there were about 25 people, and that included the front office with secretaries and all the management. So there were probably five or six American designers, and then there were Japanese designers that would come over for two years or three years, and then they would rotate out. Same with clay modelers, they would send clay modelers over for a couple of years and rotate them out. So this was a training ground, and years later we'd see the designers who came early on, moving up through the ranks of Toyota. They got very high up. They were up in the corporate boards. It was an important training ground for their designers as well.

Michael: How long were you there?

Mike: I was there 25 years and got early retirement when we moved up here.

Peggy: And Nosho was there for how long?

Mike: He was there for five years. They rotated the heads of the companies out. They'd be there for five years and rotate them out and someone new would come in. And that was something about Toyota that lot of times we'd get people over there who were in some other part of Toyota. Say somebody was a car designer and they decided they wanted them to be in finance. And they would just shift them over into finance and they would have to learn a whole new job and become a finance guy. Toyota has a history of doing that. They really challenge their employees. They'll just take them and move them into another department and say "You're here now, what can you do?"

Peggy: Whoa. So what kinds of things did you do during your time of art play?

Mike: One time I got to play car designer and I made some 20% scale models in clay and cast them in fiberglass and painted them up. At the end there was a big presentation and everyone presented their stuff and so I presented my models. Another year I did a sculpture. Boy, what else did I do? There was always something. The same year Erwin Louie was working with the plaster balloons, I was working with sheet wax and cardboard cutouts and taking photographs in a room where I used a harsh white light and cast shadows on a wall and then took pictures of the shadows. And then I would manipulate those pieces to create car shapes and car designs. Those were three of the things I did that I remember.

Michael: So while Mike is playing car designer, what's Leslie doing?

Leslie: I'd bounce between drawing and painting and doing some tapestry weaving. I apprenticed with a woman named Helga Miles. She would get large commissions through different places and then I would weave on her tapestries. She was a German woman who had her journeymanship in Europe and so it was different than how you would learn to weave here. Here it was only all based on art—do some experimenting, try something, try something else. Well in Europe, you have to go through the real regimen of learning each little nuance of tapestry weaving. So I had a wonderful experience weaving on her tapestries because we had to have the same hand, we had to have the same movement.

And so I feel like I had a very unique experience in that way. And after that I did some drawings, some paintings and some commission work for some industrial buildings but nothing was really catching on until once again my friend, Vicki made the best suggestion. You know she has paved the way for both of us. She went through the textile department with me at Long Beach and she branched off not only doing some designs for clothing manufacturing, but she then began weaving upholstery fabrics for designer showrooms. She said, "I think your tapestries would sell in the showrooms if you made pillows out of them." She was working with chenille at the time, and her orders were custom dyed. She offered to sell me some of her extra yarns.

So I designed pillows that I could weave in a day so that I could estimate their delivery. If someone asked me "When can I have it?" I could tell them how long it would take me. I never had a business plan. I didn't go to business school like some people. [Looks at Mike.] You know just trying to figure every single thing out about a business, slowly, step by step, I did some prototype pillows, took them in and they were accepted. It took about six months for the designers to really catch on to my pillows. It takes awhile at first. So I was at the point where I was going, "Is this going to work? Maybe I should do something else." And then suddenly it started taking off. After a couple of years I wanted to put some trim on the pillows but I couldn't find any trim that matched. So I went back to my history of textile art books and remembered how the Peruvians used to make cord.

In a very basic way I started making cords to go onto my pillows. And the designers then started asking, "I could use this cord right here. Could I just buy this cord from you?" And I said okay and then I had to figure out how I would do that for them. What would I charge? Suddenly, the trims were what was being wanted, so I followed that lead. The first was loop moss fringe, which I didn't even know what to call it because there's no place to learn this. You just have to do it. There's no school. No machines. Machines—well we had to figure out if there was a machine to make this, because I was hand weaving loop moss fringe at first. It took me eight hours to weave enough to go around a pillow with a shuttle back and forth. It was nutty. I knew what I wanted but I didn't know what to call it. I didn't know what kinds of machines would make it or where to get them. So I just started looking around.

Peggy: So what is loop moss fringe?

Leslie: It's a loop fringe that's on the edge of pillows. Now you see it in stores, but this was in the early '90s like 1991 when I was trying to figure this out. I had to rely on Mike's help at this point because he was used to doing a lot of research for Calty. Looking for parts, calling vendors. When I was about to give up, he started calling around and he found somewhere we could go and look at these machines. That's when it really started happening. That's when we went to a trim manufacturer in downtown LA. You're better at telling this story, you should tell this story, Mike.

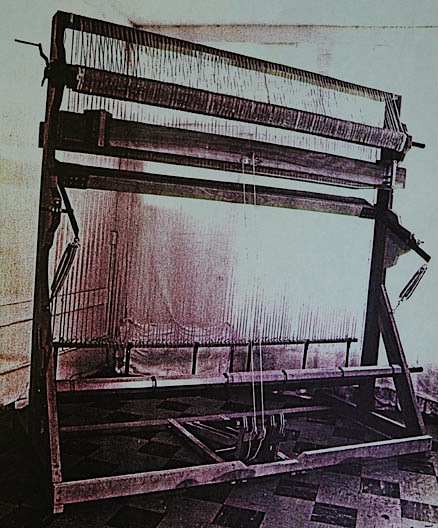

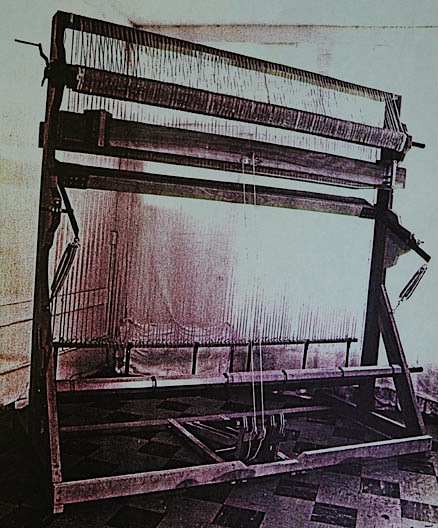

Mike: I called a guy at this factory. When he answered the phone I said, "Do you have any used machinery for sale?" I didn't know what kind of machinery we were looking for. I didn't know the first thing. But he was interested and he said, "yes, we have some machines." We made an appointment and Leslie had this little ziplock baggie of these trims that she'd been hand weaving. And he met us in the alley outside this shop because people are very secretive and protective about how they do things. We talked to him in the alley, and he looked at these trims that Leslie had, and he picked on them and pulled on them and I'm looking at him thinking this is a dead end. This is going nowhere. And he finally said, "Yes, I can help you." And we just went "What?" And he said, "Follow me." We go into this factory and it's this old four-story brick building in the Garment District in LA, and it's full of these ancient machines. These machines are a hundred years old. He had a bullion loom which took up a big room. It was probably 15 feet across and 8 feet tall with old timbers. It was built in the 1850's. It had cast iron gears. It was just beautiful. And then he said, "Let me show you the machines that you need." And he took us to another floor and there were these big old, flatbed knitters that were ancient. And that's how we got started. He said, "I'll put you in contact with someone who used to run this factory and he will talk to you." He came out to our house and interviewed us to make sure we weren't going to compete and we didn't have another factory and we weren't just trying to get their machines. He looked at what we had and we had a back house and so we bought a machine. We paid for it and we didn't know if it was going to work. It was $7500, and he brought it into the back house in the living room and started assembling it, and it took him three months to put this together. He'd come two or three times a week with a bucket of parts and he'd put his bucket on the floor and spread out the parts on the floor and he'd look at it and go, "Hmm, let's see, do I remember where this goes?" He was driving Leslie crazy because she's in the other room and we've just thrown away $7500 plus the $2500 that he charged us to clean it up and put it together. But eventually after three months he came through. We had this machine and I'm working at Calty and he would show Leslie how to run it during the day and then he would go home. And then she would show me at night. So we kind of stumbled through this thing.

Leslie: We spent the first part of our trim business experience, on our knees, side by side in front of this machine watching all the parts going. "Oh. Okay, watch out for this yarn and Oh! look at that over there, and get your fingers out of the way." It was just discovery together, these absolutely fascinating machines. Wonderful. How someone ever invented them I'll never know.

Mike: And it took me a year and a half of running this machine and experiencing it and having just total frustration with it because it wouldn't run right. I could get maybe three yards and then it would break down and then I'd spend an hour or two getting everything tied back together and this was going on for a year and a half. Meanwhile the guy who set it up, he'd brought in another machine that I was trying to learn at the same time. He moved and he said if you have any trouble call me. So I called him quite a bit. And then one day I tried one thing different from what he had showed me. And I was scared to death of these machines. I didn't want to change anything because it's all about timing and they're precise and it scared me. And one day I changed something and it worked better. I went, "Oh man if I can change one thing, maybe I can change something else". So then I started experimenting and within a couple months I had that machine humming. The difference was, he ran these machines in factories and they'd all be set up with the same yarn, so everything was done the same. And our trims would have 19 different yarns on them and every one is set up differently. It makes a difference, all the tension and everything. And that's what I had to determine was how do you make this thing work? And from there on that's really where the business took off. We could go faster.

Michael: So somebody talk about the business. What did this turn into?

Leslie: The business started as Leslie Hannon Tapestries which was handwoven tapestry pillows. I got to a point where I could see that I couldn't be weaving when I was 70 or 80. It's just very, very backbreaking. It's a lot of work. So I did need to try to figure out something else I could do and people were wanting the trims. It just sort of transitioned into Leslie Hannon Trims and I didn't do the weaving anymore. I just put that away, sold those looms and we concentrated on making trim.

Mike: And hiring the neighborhood.

Leslie: And we hired the neighbors, and they were thrilled. I had Kimiyo sew the trims together. I would ask them "What job would you like to do?" Curtis next door wove the bullions. His wife Meg was in the office with me from time to time. One of their friends, Antia, also came in and she made samples. My friend Gretchen helped sometimes, and Kimiyo also made samples. My sister put the tassels and tie backs together. Mike would turn the tassel forms on the lathe. I would paint them or embellish them. My sister would put the skirts on them. It just worked great. It worked wonderfully. Everyone was happy and it was a lot of work. It just took off. When I started I was wondering if I was going to be able to keep up with this and it got to the point where I was crying, there was so much business. Every day of the week from morning until night, every day, no change. Always just working.

Mike: There was a time there in Long Beach when we were that busy where we had a 150 orders at a time in process all the time. There was always that many orders moving through and it was very successful. It was good.

Leslie: Yeah it was good.

Michael: This was mostly custom jobs?

Leslie: All custom. It was all custom. The designers would send me a piece of fabric, tell me the style of trim they would want. I would make a strike off showing them a hand made mock up of what the finished product was going to look like. Then they would sign off on it and we would make it. We had production lists which we would have to finish and complete within a certain amount of time. It was just never-ending.

Michael: So you're making how big of runs of things? Is it very big or very small or all different sizes, quantity wise?

Leslie: I think that was the niche. We would have a minimum of five yards. At the time there really weren't very many companies who would do that. You would usually have to do larger orders. if you went to someplace like Conso or Bruck Braid and you wanted something custom you might have to order 150 yards. At the time I was looking for something to trim my pillows. I was calling around and I couldn't find anyone who would make just five yards for me. I just wanted to trim two pillows. So I realized this could be a good niche. By the time we developed all the different styles, it all just sort of came together. We made at least 5 yards of something or we'd make large runs depending what they wanted to do with the trim.

Michael: Talk a little bit about who your customers were.

Leslie: Our trims were showing in designer showrooms. Designers would shop the showrooms for their clients, and the sales came through the showrooms. At one point we were in eleven showrooms.

Peggy: All over?

Leslie: All over. In different states, New York, Florida, Dallas, Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Denver, Phoenix, L.A., San Diego.

Michael: But these designers obviously aren't doing big pillow runs for pillow companies.

Leslie: No, no, they're doing residential work usually. Sometimes we did work for hotels but usually it was residential work. Sometimes I would get sidemarks, I didn't always know where it was going but sometimes I would get sidemarks where I would say, wow, Kelsey Grammar and it would be kind of fun. But mostly I would be sending to a workroom and I wouldn't know who it was for, and they always kept it confidential too.

Mike: Well we did a lot of work for Las Vegas casinos, probably Atlantic City. We did a huge order for the Saudi royal family. We did I think 12 of their personal jets and they were all 767s and 747s. We did private resorts, so it varied. We did an order for Tom Landry, the coach of the Dallas Cowboys. I mean it wasn't for him, I'm sure it was for his wife. But we did a lot of famous people, we would speculate and then the designer would mention something and then we find out, yeah, it was them. Because it was custom it was expensive, so it was people who had money.

Michael: You've been talking past tense but I happen to know you have a whole building full of equipment and I understand it's still happening to some degree? Is that true?

Leslie: Yes. At this point we are not showing in any showrooms except for Jane Piper Reid in Seattle. You know we pulled out of all of them, downsizing, and it's just Mike and me making whatever it is we make. I have a large database of designers who still call us if they want something. And that's how I like it at this point. I do want to keep it small because at this point I always promised myself that I would be an artist and if not now when? This is it. I just must do this and so Leslie Hannon Trims is still here. If somebody calls me I'll make trim for them, but honestly, at this point, I really need to be an artist. That's it.

Michael: Ok, this feels like we're rolling up to the present. You guys came here, did you say four years ago?

Leslie: 2003.

Mike: We moved here in 2003. I got early retirement in 2002. We bought the property. We came up here looking for small house, big barn. At the time there just wasn't anything on the market we could relate to. We were here on a three day visit with a real estate agent. On the last day, the last house she showed us, there still wasn't anything. But I looked at the lot next door to this house, and I said, "Wow, that's a nice lot." She said, "Are you interested in land?" I said, "I don't know, we hadn't thought about that." And she took us probably half a mile away, and there was this piece of property, and we loved it. We bought it that weekend.

Leslie: We were so naive. "Oh yeah, we could build a house. Yeah, we could do that."

Mike: So we started that process. We bought in 99, and moved up here. Started building in 2001 I think.

Leslie: No, 2002.

Mike: Ok. Then I got early retirement, and we moved up and lived in the shop for two and a half years while we finished our place and Leslie's mother's place. And we're still working on it.

Leslie: We're not finished!

Michael: And there's a barn in process right now, which strikes me more as a really cool studio than a barn.

Mike: It is.

Leslie: Remember when we decided we were going to have a barn? Back at the artists' complex in Long Beach. We were sitting at a table and we said, "What do you think you would like in your future." Luckily we both said it would be living in a rural setting, having a barn, being artists. We knew what we wanted. It just took so long to get here. It was a good journey, and we knew what we wanted. And now Mike has built the barn and it's inspirational. It is a wonderful building. It's gonna be an art barn.

Michael: Well, I've seen it...

Leslie: Did you see it today?

Michael: We saw it in the dark tonight as we came in, but...

Leslie: Did you get out and go look inside?

Michael: No, we didn't. We'll come back.

Peggy: I've never seen it.

Leslie: We have a light. We'll turn a light on for you.

Michael: And we'll get some pictures.

Peggy: Will both of you work in the barn? I know Leslie, you were painting in the bedroom.

Leslie: I was painting in the bedroom. But I've invited the people from the life drawing sessions at SLOMA when they have down time. This summer we used the barn as well.

Mike: For me, at this point it's mostly going to be for storing my sculptures, because they're getting so big, and I've got a lot of them and my shop is just—I can hardly get around. I like my shop up here, so it's mostly going to be storage for me for a while.

It was interesting. We went to David Settino Scott's studio this last tour, and I asked him if he was doing sculpture anymore. He said, "No, because I don't have any place to put it." I thought, "Well, it's not just me."

Peggy: And his walls are covered with large paintings, and...

Mike: And large sculptures.

Peggy: Leslie, Tell us about your painting and drawings.

Leslie: I started drawing at the art museum in 2009. I attend their life drawing sessions. That got me very interested. I guess I'm mostly experimenting at this point. Getting my skills back, because if you don't do it for 25 or 30 years you're just a whole different person when you try to do it again. Your hands are different, your eyes are different, your experience—everything. But all I know is, I feel like I'm back. I'm very excited. The first time I saw something happening in my work lately was in the drawing I now call "An insidious

beginning." It's an unassuming piece that doesn't shout at you to look at it. Yet in it, I recognize a change in the direction of my work.

I just took a class with David Limrite because I wanted to know more about the paint. I've been drawing for a couple of years now, with the life drawing, and now I want to put some color in and use paint. I studied with David Settino Scott, to learn about his beautiful glaze. I took a workshop with Bob Burridge, because he's using acrylic, and his paint is beautiful. And also workshops with Joanne Ruggles.

Peggy: What does Joanne teach?

Leslie: She draws the figure. She's an excellent instructor and artist. I've had wonderful experiences each time. At this point I'm going to start doing some self-portraits. I need to find my metaphors and my subject matter. It's not just going to be life drawing. I think I'm going to internalize my direction and find the metaphors. It's hard to explain.

Michael: I think that's a very good comment though. One of the most important things you do as an artist is to find your own voice. Nobody knows what their voice is when they start. You know that you've got a little bit of talent and you know you enjoy doing it. But it takes a long time to really figure out what you have to say sometimes.

What about you, Mike.

Mike: Well, it happened when Leslie and Robert Oblon—we've known him all these years—both decided they were going to do art. It took me a little longer because I was still working on the house. It's funny, because when I was working at Calty, people would ask me what I was going to do when I moved up here. And I thought, "I don't know, maybe I'll do some sculpture." To me it was just this big blank. I didn't know what that meant. But it meant something. So when I decided, "OK, it's time for me to do something," I wasn't sure what to do. But I had some copper, and I had all my hammers left over from metal smithing school, and I had a couple of stakes to pound on. I started beating on copper, and everything I did turned out to be a human figure. So I thought, "Well, OK, I'll go with that. This is looking like art." So that's really how I started, and I just got deeper and deeper, and each time I would challenge myself to do better than I did the time before. I still do that. I think that's one of the things that drives me. I enjoy working with the metal so much, and the fact that I can actually make art with it is pretty exciting. I've been branching out. I've been doing birds. That's my focus right now. The human figure, the form, and the energy—my figures are always in motion, the birds are always in motion—I just like the energy. So that's where I'm going, plus experimenting with techniques and new materials. I like doing that.

Michael: Well, you have a new material thing that's created quite a stir around here, and that's newspaper and duct tape. Tell us a little about how that came about and where it's going.

Mike: Part of the thing about working with copper and metal smithing the way I do it—And I consider that my technique is not pure metal smithing. It's kind of a combination of metal smithing and blacksmithing, because I really beat the metal up. I don't care if I rip it or tear it, or what happens to it. And I like all the hammer marks. But the problem with that is that you can only work half a figure at a time. It's hard to hold. You can only go so big. You can do it in sections, but it was frustrating for me at the time. I wanted to do some sculpture that I could do in 3-D. I wanted to go big because everything I was doing was small. So I started making a form. I thought I needed a form and maybe put clay on it and maybe cast it, but then, if you're talking about casting a full figure in bronze, it's many thousands of dollars. So even as I'm doing it I still didn't know where I was going with this. But I was packing newspaper and wrapping it with duct tape just to get the basic form so I could put some clay on it and see where I was going. The closer I got to the surface with this newspaper and duct tape, I realized that I could see form in that. I could make muscle. I could make bone. So I just challenged myself to see how far I could go with just duct tape and newspaper. I really had a lot of fun with it. I don't know if I'll do any more, but I feel like I have achieved my goal.

Michael: One of the issues with duct tape and newspaper is that they are both very transient materials. You've worked with duct tape, and you know that after a few years it gets brittle and crumbles, and there isn't much left. And newspaper does the same thing.

So that's kind of a challenge with that material. I guess it would almost have to be a limited experience at some level.

Mike: That came up right away. As soon as I could see that these could actually be a sculpture themselves, I started thinking about how the duct tape could be preserved. I called 3M and got their tape department, and I asked to speak to someone about how you can preserve duct tape. And they go, "Oh, you can't." So I asked, "What do you mean? There's got to be some way that you can preserve it. Something I can do." "No. There's nothing you can do. We can't tell you anything." They just didn't want the liability of saying there's something you can do, and then when it fell apart I'd be mad at them or sue them or something. But my theory is that it's the air that breaks down and dries out the duct tape. I've seen it. it turns powdery and there's this gauze that's left. So I experimented with some sealants and I went with a matte medium that acrylic painters use to seal their paintings. Some of them are flexible. So I bought some and took it to the local hardware store and they put it into a spray can for me. I sprayed the duct tape figures with that, and it didn't change the look. Some of them are going on three years old and they look brand new, so there's something to sealing them off. I don't know how long it will last but they're still looking pretty good.

Peggy: Leslie, what are your inspirations? Particular artists?

Leslie: Sargent. Lucian Freud. Alice Neel. Andrew Wyeth.

Michael: Mike, you want to give us a list of your influences while we're at it?

Mike: Well, I think first is Rodin. I just love his sculpture. I love the power and the energy that his bodies show. Also Robert Graham, who died a couple of years ago. But I saw his last show at USC, and he went very abstract with his figures. I loved that. His figures are just amazing. But those two are the artists that inspire me the most. Mostly Rodin.

Michael: I can see that. There's one thing I want to touch on for a minute. The trim business is really and interesting study in entrepreneurial creativity all by itself, and it took off, and did very well, and provided you guys with a lot of income and support over the years, and is still in the mix.

You had a remarkable career, Mike, as a model maker for Toyota. That's about as close to art as you can get without it being art. So you guys have had kind of unique careers. Yours was corporate, but both of you have been able to really have an interesting mix of creativity and control over your own lives all through the years. And now you've taken it a step further, and you've backed away from some of that...

Leslie: We're reinventing ourselves again.

Michael: What would you tell someone who is just starting out? Someone who's either been in a career they didn't feel was particularly fulfilling, and now is ready to make a leap, or to someone who is young and hasn't figured out how to do it but they know that they want a creative life. What would you say to that person?

Leslie: It's amazing what can happen when you follow an opportunity. Be open to the fact that there are insidious beginnings. Like the time when I made cord for my tapestry pillows, and the designers asked if they could buy just the cord, but in a different color. That was the turning point that lead the way to Leslie Hannon Trims. I narrowed the focus and chose a path. It opened up and developed into another business that was very successful.

The collaboration between Mike and me was the only way it happened. We couldn't have done it without each other. We each had something we contributed.

Mike: I think it would be so difficult. It's hard for me to relate to where young people are with their lives these days because everything revolves around computers and cell phones, and that didn't exist when we were that age. For me working with my hands was always key. I love to make things. I love to build things. I love to fix things.

I was in school. I was a business major. I knew I didn't like that, but the Viet Nam War was on. You had to stick with your major once you committed, so I got the business degree, but at the same time I'm thinking, "I like ceramics. I like doing stuff with my hands. I think that's always been my focus all along. If you know you're good at something, and you like doing it, you may have to do other jobs. You may have a totally different career. But don't give it up. Always have it there, always work on it, always be thinking about it. Because like Leslie said, you never know when the opportunity is going to present itself and you've got to make a decision. You know, are you going to go this way, or are you going to follow your heart. That's something that people are just going to have to figure out.

|