The Windhook Interview: Larry LeBrane

Larry LeBrane is a glass and multimedia artist working and living in Los Osos, California. His studio is in San Luis Obispo, and he's known nationally for his avant garde stiletto heels and tea cup lingerie. What struck us about Larry as we talked to him is that he's one of those artists who consistently made choices that kept him on the artistic path from an early age. As you read through this interview, and look at the images of Larry and his work, you'll get a sense of the infectious humor that shows up in everything he does. Let's jump right into the interview.

Larry LeBrane is a glass and multimedia artist working and living in Los Osos, California. His studio is in San Luis Obispo, and he's known nationally for his avant garde stiletto heels and tea cup lingerie. What struck us about Larry as we talked to him is that he's one of those artists who consistently made choices that kept him on the artistic path from an early age. As you read through this interview, and look at the images of Larry and his work, you'll get a sense of the infectious humor that shows up in everything he does. Let's jump right into the interview.

Michael: You studied art at Otis Art Institute in LA. We’ll get back to that, but as I recall, you are not originally from California. Tell us a bit about your roots, and how you ended up in California.

Larry: I was born in New Orleans and at age 2 my family moved to LA, so I’m practically a native. And being raised in LA, I feel like a native because I wasn’t really exposed much to the New Orleans culture. I’m mixed. I’m part Black. If you’re part Black, some people say you’re all Black. Or in New Orleans, creole which is however you want to look at it but it’s a mixture of anything that is New Orleans melting pot. Native American, Portuguese, Spanish French, I don’t know, I haven’t been tested for all of that. But I know the Black part’s there. So there it is.

I was in LA yesterday, I’ve been going to LA now maybe once a month on business. Anyway as I’m pulling into LA I see the William Mead public project housing, William Mead Homes right off the railroad tracks just as I’m pulling into LA and I see where I started, but from about the 6th or 7th grade we lived on what used to be Santa Barbara Avenue. It’s now Martin Luther King. We lived near Western and Arlington, just before Leimert Park. So I used to walk as a kid. Of course we walked all over LA, I used to go to the Coliseum or Exposition Park. We would walk that far to Vermont, Manual Arts area. and so we would play around it. From that end all the way to Baldwin Hills. They were just building Baldwin Hills. We'd go up in the hills there and peek into rich peoples’ homes.

Peggy: I remember when that was starting up.

Larry: My family put me in Catholic school for 7th and 8th grade. So from 9th through 12th grade for high school I went to Mt. Carmel High School in Los Angeles. It was on 71st and Hoover. It’s not there anymore but it was an all-boys Catholic School. It was a great education. I had 4 years of Latin, I had two or 3 of typing and I didn’t think I’d ever use typing 'til computers came along. And now I can do it with 10 fingers. It’s like riding a bicycle. Also the Latin, I hated studying Latin but it gave me a great appreciation for the English language. After that I saw the connection between other languages and Latin. I was an altar boy back then. And my family moved to San Bernardino area just outside of Rialto, a little town called Bloomington. My family moved, it’s between Fontana and Rialto.

Peggy: What did your Dad do?

Larry: My dad was a welder. He moved from New Orleans to weld during the war, to weld ships. He was a fabricator. He never wanted me to be a welder so I never learned welding from him. And I wish I did! So he moved to the coast to find work. I’m 18 months older than my next brother. So we were both born in New Orleans and the other five were born in Los Angeles.

Michael: Was there any art in your family? You didn’t have it in school.

Larry: No there wasn’t any in the family. Didn’t have any art exposure but I always drew as a kid. I liked drawing and in high school I figured out I wanted to study it. So I decided to go to community college. I went there 2 years, got my AA, built a portfolio. I mean we were poor. We weren’t dirt poor because we always had food and we had shelter and we had clothing, especially me. Everybody else had the hand-me-downs. We learned right away the difference between wants and needs.

Peggy: Did your mom work?

Larry: No she was a stay at home mom.

Peggy: What did your parents think about the art?

Larry: They didn’t understand. My Dad wanted me to be a doctor I guess.

Michael: He wanted you to get a "real job".

Larry: Get a "real job", yeah. But they came to my graduation from Otis when I got my masters degree and they listened to a bunch of speeches and saw what was going on and they said they didn’t realize people were serious about this and what a big deal it is. It was a whole new world to them. So I got my portfolio together and I came to LA to school. I went to Art Center which was in West LA the time, on 1st or 3rd.

Peggy: And it wasn’t Chouinard?

Larry: No, Art Center, it was commercial, they trained people for commercial art, graphic arts, a lot of car designs.

Peggy: Before Art Center moved to Pasadena then?

Larry: Yes, before Pasadena. Then I went to Otis and Chouinard was around the corner. So I only went to those 2 schools. At Art Center, you go for 4 years and get a bachelors degree but you can’t work in the first year. Too much homework. But Otis gave me credit for my 2 years at community college, so in 4 years at Otis I got a masters degree. My first semester I paid for. The rest of it was scholarships. It was need and portfolio based scholarships so I got pretty much a free education for a masters degree.

Michael: At a very not-free school.

Larry: And of course I ended up teaching at community college. I believe in the value of community college. You know some people say it’s high school with ashtrays but there’s both. There’s serious students there and there’s honor students that go on to Berkeley or Davis or whatever. And there’s people who just shun community college who go straight out of high school, they have no study habits, they drop out, they’re not ready for it. At community college you learn how to study and how to be one of people in a lecture hall, you’re not special to the teacher, you know.

Peggy: When you went to Otis, you lived at home?

Larry: My Dad stayed in LA, the family moved out to a 5 acre farm in Bloomington. I was only in Bloomington for 2 years. Then I came back to LA, first I stayed with my Dad. We couldn’t get along and I moved out and I just scraped by on my own. Put myself through. When I was at Otis, I looked around and I saw people graduating ahead of me and they’d end up in jobs that had nothing to do with art. So I said, "If I’m going to get a masters degree, what can I do with it?" It just kind of fell in place. I decided to go into education because I saw people getting teaching jobs. And in those days, with a masters degree you could get a teaching credential without going through the K-12 certification and all that. You got a credential for life. But meanwhile, the draft got me. I had no more student deferments. As soon as I graduated I got married to a fellow student there. The marriage ended up lasting about 10 years, but anyway, right after I got married I was

drafted and it turned out to be a great experience. I just spent two years in the Army. She taught art for the Army for special services. She had a GS-7, which is the equivalent to an officer, like a Captain or Lt. or something like that. We ate at the officers’ club, we lived off the base, we were in Korea during Vietnam. It’s kind of funny too because they trained me for computers. So here I had an Art degree and my masters. I went to Army Adjutant General School for computer training. And in those days it was collators and punch cards so they ended up sending me to Seoul, Korea, 8th Army Command. It was a great job. I had a night shift. We had a Korean maid. We lived on the economy and it turned out to be great. And we would take leave to Japan for 2 weeks. We slept at Army bases, saw a lot of the art. We studied Japanese history, art history. We went to Kyoto, Nara, Tokyo of course. We went all over Japan. We rode the bullet train. This was a culture shock too because in those days, this was ’66 to ’68 and Korea was underdeveloped. It was like Tijuana, so to go from there to Japan was a big shock. Japan was into their tech boom. It was kind of like going from Tijuana to San Diego. It was weird. It turned out to be a great experience anyway. Then when we came back I got a computer job on graveyard shift. Meanwhile I applied for teaching because I wanted to use my degree. I got a job in Fontana, back in the Riverside area. It was teaching art, and I was only there a year before I switched to Rialto, which is where my wife was. She had a job teaching art, and the reason I switched was that district didn’t give me credit for my simultaneous degree. In other words I got a bachelors and masters at the same time and they didn’t recognize it. Some districts recognized it and some districts didn’t. So I just moved.

drafted and it turned out to be a great experience. I just spent two years in the Army. She taught art for the Army for special services. She had a GS-7, which is the equivalent to an officer, like a Captain or Lt. or something like that. We ate at the officers’ club, we lived off the base, we were in Korea during Vietnam. It’s kind of funny too because they trained me for computers. So here I had an Art degree and my masters. I went to Army Adjutant General School for computer training. And in those days it was collators and punch cards so they ended up sending me to Seoul, Korea, 8th Army Command. It was a great job. I had a night shift. We had a Korean maid. We lived on the economy and it turned out to be great. And we would take leave to Japan for 2 weeks. We slept at Army bases, saw a lot of the art. We studied Japanese history, art history. We went to Kyoto, Nara, Tokyo of course. We went all over Japan. We rode the bullet train. This was a culture shock too because in those days, this was ’66 to ’68 and Korea was underdeveloped. It was like Tijuana, so to go from there to Japan was a big shock. Japan was into their tech boom. It was kind of like going from Tijuana to San Diego. It was weird. It turned out to be a great experience anyway. Then when we came back I got a computer job on graveyard shift. Meanwhile I applied for teaching because I wanted to use my degree. I got a job in Fontana, back in the Riverside area. It was teaching art, and I was only there a year before I switched to Rialto, which is where my wife was. She had a job teaching art, and the reason I switched was that district didn’t give me credit for my simultaneous degree. In other words I got a bachelors and masters at the same time and they didn’t recognize it. Some districts recognized it and some districts didn’t. So I just moved.

Michael: Was this public school?

Larry: Yeah, it was Fontana High School where all they wanted to draw was Hells Angels skulls. There were kids from Hells Angels and they wanted to draw skulls, crossbones and skulls.

Peggy: And their uncle was in Chino and all that.

Larry: And I don’t mean Chino pants. [The reference was to a California state prison]

Larry: I switched to the junior high and then I was there in the district where they gave me credit for my degrees. In ’71 I applied where the other Otis graduates were at Orange Coast College, Costa Mesa, a community college. I got the job in ’71 and I was there the next 32 years. When I got that job I had died and gone to heaven. My hours were cut in half and I was making ten grand a year more and I didn’t have to deal with parents. With community college I didn’t have any discipline problems. It was in Newport Beach.

Peggy: Yeah, one of the wealthiest community college districts.

Larry: I was near the beach, Newport, Laguna Beach, Costa Mesa. I was there for the next 30 years and it was an easy gig. I never worked more than 24 hours a week and I didn’t work Fridays. You know it was a union thing. It was a great run but I did what I wanted to do with my degree. I wanted the security. Like I said I saw these other guys coming out ending up in jobs that weren’t related or they were in a warehouse starving. I wanted security.

Peggy: You wanted to eat.

Larry: And I had all kinds of great medical benefits. I didn’t do as much art work as I would have liked to have done but I always made it a point to do a piece for the annual faculty show, because I wanted the students to see what I could do. I was around artists, I knew what was going on in the art world and the great thing about teaching was it helped me understand art better because I had to verbalize it to other people and I had to verbalize it in many different ways to get people to understand it. So going through that helped me to understand it. I mean understand the process. Or verbalize the process.

Peggy: It’s different when you have to talk about it.

Michael: One of the things I wanted to talk about was the importance of community among artists. And how your career tied in with that, because I’m sure it did.

Larry: How so?

Michael: The person that didn’t take the path that you did ended up in an office job somewhere, if you’d gone with the computer job, it’d be really hard to keep your connection to the art world and to creative people doing creative things.

Larry: Yeah I kept connections with other teachers who were like-minded artists. It was this close little community and I didn’t really know many people outside of there.

Peggy: What were you teaching?

Larry: The whole time, I taught beginning drawing, I taught color and design, I taught crafts. Within the crafts I taught stained glass work, leather, jewelry, casting, I did a lot of different materials and that’s why I feel comfortable doing mixed media and going back to being poor, you always learned to do stuff yourself. I worked with my hands a lot. You learn to be resourceful and you don’t throw anything away. You know, that’s repurposing, and they didn’t have that word back then. You know, recycling. I was doing that a long time ago.

Michael: So you retired from Orange Coast in 2003 and moved directly to Los Osos?

Larry: Yes. In the summers I’d always go camping along the coast because I don’t like heat. It’s too hot every place else. So Ronda and I always came to Morro Bay because it was enough of a days drive that you could still get there in daylight and set up camp. Then one year a Cal Poly student in the kite shop on the Embarcadero told us about Los Osos. And this was about 8 years before I retired. So we went to Los Osos and we fell in love with it. Every year we came back. We would go around looking at houses in Los Osos. We never really liked Morro Bay that much because Morro Bay was too touristy, too close to the freeway, and Morro Bay didn’t have many trees.

Peggy: Yeah, that’s right.

Larry: Los Osos had all that. Plus it was affordable property on the coast. Timing was everything. When I retired I had just taken a trip, a sabbatical for 60 days to Europe. When you take a sabbatical you have to stay 2 years. So I said to myself, "I’m getting close to retirement, full vestige on the retirement, I’m going to be 62 years old, let’s take this trip now, while they will pay for it." So we took the trip. We went all over Europe to the museums, France, Spain and Italy. And it was a great trip. I had to serve 2 more years, but that’s the way we planned it. About the time we got out we had one of these budget crunches and they were trying to get rid of people anyway. They had a golden parachute and they gave me an annuity on top of my retirement so I decided it was time to go. And speaking of timing, timing is everything because we were living in Irvine at the time. I had sold my condo and we were living in Ronda’s condo and so I retired in ’03 in May, we sold the house in June and we pulled in to Los Osos the 4th of July. We pulled in to Ralph's Los Osos at 9:00. Fireworks were going off in Morro Bay. A U-Haul truck and my suburban with a cat. We leased a place for a year. We wanted time to look around and buy, but in July, August, September, October, housing prices starting creeping up, like $12,000 a month! We had to do something fast or we were going to be priced out. We decided to buy a mobile in Morro Shores across from Sweet Springs. The house went up on the market and we got it for the asking price on the first day So we broke our lease, and we felt lucky that we got in. We love it, we got in just in time.

Peggy: It’s a great location.

Larry: The only problem is you can have a minimum amount of storage or shed space and there’s no garage. That’s why I rent a studio. And I figure eventually I do have a room where I can do my 2-D art, I can paint and draw but I can’t do anything industrial. Eventually I’ll just go back to “drawrings”! Making my “drawrings”. You know with papers and pencils. I can always do that. But I like working with my hands. I like the 3-D experience of manipulating stuff. I probably always will but I enjoy both.

Peggy: But you need the space to lay it out and leave it.

Larry: So it’s been a sacrifice but it’s been worth it, I don’t have any regrets.

Michael: This brings us full circle on the question of community, because you’ve left the college art environment where you’re teaching and rubbing elbows with students and teachers that are in the arts. You’re still doing it but you’ve got to make the connection to artists.

Larry: When I retired I decided I was going to make art full time. I had a pension, I had my food covered, my security, my medical, and all that, so I had the freedom to explore my art. And of course, making art, you want people to see it. So I joined the Art Museum, then called the Art Center.

Peggy: Did you meet other artists?

Larry: Not till I joined, that’s how it happened. I think I wanted to enter a show, so I had to join a group to enter the show. I belonged to the sculpture group and the craftmakers group. I figured my functional art is covered by the craftmakers group and my fine art is sculptural, where it’s expressive. And I feel that in order to justify the studio, I have to balance both all the time. Make some of it for money and make some of it for my soul. And one pays, one supports the other. So then I started being active in the groups and meeting other artists by placing my art in different galleries or stores or whatever.

Michael: Well being involved in the sculptors group I know that you’re just a little more than active. Quite active.

Larry: Well I do have the luxury. It wasn’t planned this way, but my wife, Ronda, is my manager, my PR person, she talks to the people for me. She supports me and it just happened that way. We didn’t plan it that way but she’s very good at it. She comes from a business background. I’m very fortunate because she gives me more time in the studio where I don’t have to promote myself, and like I say, she’s very good at it.

Peggy: Where did you and Ronda meet?

Larry: At the Westminster bowling alley, they had a bar called the "Press Box", and in the bar they had a dance floor. I went there for West Coast Swing dance lessons. And West Coast Swing dance is a little bit slower than the jitter bug so it’s an older group. It’s usually danced to the blues. We both have a love for that and we went dancing all the time and that’s how we met. She was in corporate America, I thought she was a corporate . . . I won’t say the word. But she turned out to be a genuine person with a great sense of humor. She’s funny, she’s very smart, very creative. She’s a creative thinker and that’s what I like about her, and we laugh all the time. We just have the same perspective about life. We call it the “absurdity quotient”. We’re always bouncing laughs off of each other. It’s great but I’m very fortunate to be in a career partnership as some couples are and I don’t have to think about some things.

Peggy: Yes, we’re actually thinking we need to do a something on couples in the arts.

Larry: Like Bob and Kate Burridge.

Peggy: Exactly, like Bob and Kate Burridge, Randy and Lisa Stromsoe, it’s like that.

Michael: We’re finding over and over these couples where one partner is an active artist and the other is essentially the promotion and marketing manager.

Peggy: It’s just really complementary.

Michael: It’s a remarkable combination when you can find it.

Larry: It is and as I said in our case it was accidental. We didn’t plan it that way. We know some couples where the spouse says, “That’s your thing. I don’t want anything to do with it”. And that’s fine too, but I’m just saying that I’m very grateful that I’m in this position.

Peggy: And she does it so well.

Michael: One of the issues that many artists bring up, and we’ve heard this over and over, is “I feel like I need an agent, someone to represent me.” And when you have the kind of partnership that you do, you actually have that in a way that many people don’t.

Larry: I think it’s also easier to sell somebody else’s work than your own. I think selling yourself is a little harder to do for the artist. And I’m not a good salesman, I’ll knock on the door and say “you don’t want to buy this painting, do you?” I used to say, “You don’t want to buy a T-shirt, do you?” I taught silkscreen printing for 25 years and this was in Newport Beach where they all wanted to make their own clothing line, like Quiksilver or Mossimo, that’s the breeding ground. And I even had a couple of silkscreen printing t-shirt shops, as part of the curriculum. Also when I taught I always taught beginning level courses. For example a drawing class, a beginning class called freehand drawing. For two reasons, the first was that it’s an elective so it’s always filled up. I never had enrollment problems, I never had a class cancelled because there wasn’t enough enrollment. And the second reason was that I always felt more comfortable teaching skills or the tools you use to make art, rather than the advanced classes where you start teaching creativity. I think you can expose people to creativity but I don’t think you can teach it. I think you can nurture it or develop it but I don’t know how I would teach creativity. So I always felt more comfortable teaching the base courses. I teach drawing now for Cuesta College. I teach a beginning class for Cuesta for people who’ve drawn some, to people who’ve never drawn before. And I enjoy that because I feel like I can objectively teach the subject rather than put my taste on it and say this is good or this is bad. I can say this works or doesn’t work. But an important part of the process, I believe, is critique, because you can cover so much territory in a critique and it’s a time saver. Also I tell my students I don’t teach them how to draw, I teach them the tools that they can use to teach themselves how to draw.

Peggy: That’s a class I need to take. You talk about the craft work tending to be more functional and the fine art for your soul, so where do those ideas come from, what inspires you?

Larry: For the functional art, its something I made and it sold so then I made it again and it sold again, so it becomes a part of the inventory. I keep making them and they keep selling and you just find that out through the whole process. The whole process of creativity is trial and error. The more education and more exposure you have the more you’re just trying to reduce the number of errors, and get more successes. But still it will always be trial and error. There’s no such thing as failure. Failure teaches you not what to do. So that’s valuable. Especially with glass, I very seldom say I give up on it, I can’t do anything with this I’ll throw it away. I’ll have 2 or 3 things going on at the same time and if I get stuck on it I’ll go to another thing.

Michael: At least you can always make stringer out of it. (Larry had just shown us a technique for making long thin strands of glass from scrap. They are used to create visual lines in his designs, and he called this material "stringer".)

Larry: Yeah at least you can melt it. Or you should see my wife’s garden. It’s full of used glass, little light catchers all over the place, broken shards of glass that didn’t work out. So it’s repurposed.

Peggy: Tell us something about the big commission in Santa Barbara that you just installed.

Larry: It’s for Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital. We found out through Rosanne Seitz at the Network, the Gallery at the Network, where I’m a member, there’s like 35 artists in there and I’m one of them. And she saw me at one of my first shows. I did outdoor shows at Dinosaur Caves. She saw my work and she invited me to join the Gallery. And that’s great, I did Dinosaur Caves for 2 years. You know you put up a tent and show your stuff. I was always worn out the next day. I didn’t like putting up a tent and packing and unpacking glass but the exposure was great. I didn’t sell that much but Ronda stood by the tent and had people sign up with their emails. Ronda was marketing the whole time. She would bring them in so I got a lot of exposure, so it was valuable that way because it set the stage for what was going to come so it wasn’t really a bad experience.

Michael: It was really a foundational activity.

Larry: Yeah, Rosanne told us about this Call for Entries from this company called Aesthetics, Inc.. They’re in San Diego and they place art in different institutions, different businesses and they were placing art for the new wing at Cottage Hospital. There was a lot of paperwork to fill out and Ronda is good at that. I looked at the paperwork and went ahhhh. And Ronda just wrote up the proposal. So she wrote the proposal for the artwork and they ended up choosing 10 artists from the Central Coast.

Michael: I remember seeing that, there were a lot of things available.

Larry: A lot of sculpture and 2 dimensional work, and it’s beautiful and I’ve been down there, a lot of bronzes they have a beautiful sculpture garden. It’s amazing and they have connected the healing power of art to the hospital setting. And that’s what's great about it. Somebody put up the money to have the vision to do that.

Michael: And there were big commissions for the work.

Larry: Yeah, $20,000 - $30,000. So we sent it off and then I got sick. I thought I had the flu. And it just kept hanging on and I started getting double vision. I went to the eye doctor and he couldn’t find anything. He changed my prescription. I went through all kinds of tests to find out what it was. First the cheap body fluid tests and then finally we go to the MRI. And the MRI showed that I had a tumor on the pituitary gland that was putting pressure on the optic nerve. It sits between the optic nerves. So they found it and they said okay you take these hormones. And the next day I felt better. It was weird. I felt like I could do my thing again. So that gave me some time to schedule surgery. It still had to come out but it wasn’t urgent because I could function with the medicine. So we scheduled surgery for November 29 which was the Monday after Thanksgiving and it was a 2-hour surgery. They go in through the nose, it was here at Sierra Vista Hospital with a neurologist named Phillip Kissel, the best neurologist in the county. So I didn’t have to go to UCLA or one of the schools because I have good insurance. I didn’t have to wait to go to the University hospitals and establish residence and all of that. It was a 2-hour surgery, I was in on Monday, I was out by Wednesday and the next nine weeks were hell, with headaches. You know it was a bad recovery. Headaches, narcotic pain management and just terrible feeling. Just headaches and you couldn’t sneeze or laugh too hard which was hard with us. Because the pressure would blow the hole, the little hole, they stopped the hole where they went in through the nose, through the nasal cavity back to the skull, drilled through the skull, you know on the other side of the nasal cavity, microscopic surgery. They patched the hole up and if it leaks, spinal fluid could come in and you’ve got all kinds of problems. So anyway, about 3 weeks into this we get the letter from Cottage. They said, “we want you.” I told them this was great, but I don’t know if I can do this, don't know how is this going to end up. They were great and they said we’ll work with you. We’ll give you extra time. So I did some sketches and proposals and they critiqued them. Actually they allowed $1000 just to do the sketches. And they sent the checks right away.

Peggy: That’s amazing.

Larry: It was an $8,000 commission and they said you have this niche. It’s on the 2nd floor east corridor. The money was up front so they said you have to design something worth $8000. I was thinking of all this representational stuff with missions and seagulls and trees but they wanted something more abstract. They suggested something abstract on water movement. That was great, more freedom.

Michael: And glass is a very good medium for representing water!

Larry: The only problem was I had to work within certain restrictions. I ended up doing three rows of 6 panels, three different sizes, 6 x6 , 12 x 12 and 12 x 24. And it was all on this theme of water but because it’s in this healing place the water movement had to be calm and from a design standpoint all the variations of water movement would have been fantastic to splash in different directions and go diagonally and vertical. But I had to stay horizontal so I had a limited palette. The blues and the greens of water. So I had to be restrained. The only thing I had to get the most variation was the texture. So the glass has at least two firings. One is a flat firing and the other one is where the glass doesn’t go all the way in, it’s a texture firing so you want to touch it. And with clear glass on top of it it looks like water drops or whatever. And it had a lot of bubbles. (laughs)

Peggy: So what’s next?

Larry: Well you know it was important to do the Cottage job because everything you do and put out there is an opportunity. You don’t know who’s going to see it, who’s going to want it, who’s going to want more. And it was important to perform for Aesthetics, Inc. so if they have something else come up, you know they call artists to schedule their installs and they have artists going “you stressed me out, I don’t know if I can do it.” That’s the worst thing you can do, you know, you’re dead, you’re not coming back. That’s the worst thing you can do for your career. So I knew once I committed I had to perform. It was a great experience because it really was my first public commission.

Peggy: So how did that work? You’re under contract to the Aesthetics people and they have the contract with the hospital?

Larry: Right.

Michael: You didn’t answer her question though, what’s next? Where are you going from here?

Larry: You know I devoted my whole time to this project and a lot of my inventory went down. I didn’t participate in any Christmas sales or anything like that. I probably knew that was coming up. I do have students to pick up the slack with the studio rent. So Lisa Stromsoe wanted more corsets, so I’m filling up the corset order and I’m just building up my inventory to see what comes up next. I don’t have anything specific lined up as far as commissions.

Peggy: And what about the stuff for your soul? What’s your next?

Larry: Yeah that’s a good question. . . my soul food, what’s on the plate for my soul food? There’s a lot of people doing fused glass, which feeds the lessons and a lot of people are addicted to it, so there’s a lot of competition for fused glass sales. So the one edge I have, which is the one I’m interested in is, I’m going to develop my own molds, design my own molds that I can cast in glass for service ware, like plates, dishes. And that would be different and nobody else makes it. That’s what I want to do, to get sort of a good design but more of a mass market item that I can do over and over again.

Michael: You just brought up the lessons, the teaching that you do. You do community college classes and you teach in your studio? We’re always interested in how people supplement, to make ends meet, because quite honestly very few artists make ends meet just selling art.

Larry: I’m happy to make it pay for itself. Because I’m not hungry, I have a pension, my food and shelter is covered, so I have the luxury where I can do it the way I want to do it and I’m not hungry to make the same thing over and over a thousand times just to support it. So the lessons support it, the sales support it, but I don’t feel the pressure to keep up with it. I think the worst thing I can do is to do the same thing over and over, it’s not art anymore. So you’ve got to find out where that point is where how many times are you willing to repeat it, it gets boring if somebody comes and says can you make me 50 of these. No, I can’t.

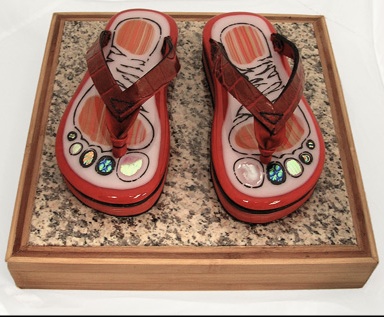

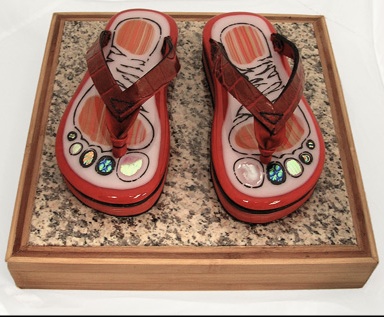

I’ll give you a story. I did a pair of shoes, glass flip flops when I was doing flip flops. I finished them on a Friday and I was showing them on a Sunday at Dinosaur Caves. The show goes from 10:00 to 4:00 and this woman walks up and says, “I love those shoes, I want to buy them.” This was at 10:15. I had just opened. I said, "ok, I’ll sell them to you but I can’t give them to you until 4:00. I just finished them and nobody’s seen them. I want people to see them. So the money wasn’t really . . . I said I want more exposure, exposure’s more important than the money at that point. She said ok, she gave me a check and said I’ll be back at 4:00. So meanwhile, halfway through the day, another guy comes along and he says “I want those shoes.” I said I sold them but I can make another pair, but they won’t be just like that pair. I said, "they’ll be crazy like that. You tell me what colors you want, and I’ll make another pair." So he said ok. Meanwhile I’d been talking to Ronda about it and Ronda pipes up, “He’s thinking of making high heels next!” He said, “oh, tell me about it.” He asked what I was going to use for the base. I said I had this diamond plate aluminum that looks pretty cool. He said, "Oh great, I’m lining my garage in that stuff!" He has a house in Shell Beach. He’s in the oil industry in Bakersfield. He's got a house in Tahoe, he’s got a plane, he calls the pilot to fly him to SLO, so he can smoke his cigar and drink wine. I never would have had this conversation if I had let the woman take her flip flops at 10:15.

Anyway, I finished the shoes for him and started working on the high heels, so we go to his house to show him the high heels I'm working on. His house is right on Ocean Avenue on the cliff of Shell Beach. The cliff is right across the street. So we go in the house and there’s the pair of shoes, sitting on the floor like a doorstop. But it’s white tile, white carpet leading to the living room and the shoes are there and it tells you “take off your shoes” without saying a word. It’s a hint. That’s where the shoes go, take them off. That was so cool. At first I thought, why’s it sitting on the floor but then I got it.

Peggy: He just walked by at the right time at Dinosaur Caves.

Michael: So if you had sold her the shoes let her take them home none of that would have happened.

Larry: Yes. I finished the stilettos and I said, I want people to see them, no one else has seen them so I want to borrow these for awhile and enter them in shows and stuff because that was more important.

Michael: So you just never know when it’s going to lead to something.

Larry: Exactly. You know the exposure is worth more than a quick sale. So just like with these shoes, I had the stilettos for a year, showed them around, and at the end of the year he bought them. Which was fine. if he hadn't, it would have been fine. I had the exposure, I became the shoe guy.

Michael: You know this whole thing about the shoes, touches on another aspect of your career that I’ve been impressed with and that’s creativity in ways to show. The !Romp Show.

Peggy: The Romp Shoe Store.

Larry: Ronda’s idea. Ronda walked in there and they said they were having their 5th Anniversary and Ronda said you want to have a shoe show? And they agreed and I had a one-man show and it was great marketing because they just moved onto Higuera Street downtown, and the exposure was great. My stuff was in the window for a month.

Michael: And the whole idea of a shoe store, a high end shoe store with art that is shoes, interspersed with the for-sale, wearable shoes. Well it’s all for sale, but with the footwear it was just brilliant. It was a great idea.

Larry: I mean it wouldn’t have been a good idea at a Payless Shoe store.

Peggy: It was a fabulous show. It all looked great.

Michael: I think we went to the first one and it was quite a party. And there were people actually there trying on shoes at an art show.

Larry: Yup that was Ronda’s idea, great marketing. So when I’m ready I want her to go to Fanny Wrappers for a corset show. And you have to go to the Mom and Pop stores, you can’t go to Victoria’s Secret or you can’t go to chains, they have to go up the chain of command. That’s why Fanny Wrappers.

Michael: You had a traveling show with the high heels, right?

Larry: Yes. What happened was, a year earlier, in the New Times I saw an advertisement for the bike show, the Tall Bike Posse, and I said this looks like a great show. I’m going to do it next year, I want to be in it just for the exposure. So I decided to do a pair of shoes using bicycle parts but I didn’t know how I was going to do it because I didn’t want to buy a bicycle or get an old rusty bicycle and take it apart. Plus I needed two of everything because I always thought the shoes should be made in pairs. I always made them twice. So one day I was walking in Los Osos and I went to a yard sale where this guy had a big bag full of bicycle parts. He was planning to build his own recumbent bicycle and he gave up on the project, so I bought the bag for $5 and I had all

the pieces I needed. I built these high heels out of bicycle parts and I was putting beads around the platform. I stood back and looked at it and I said “that’s a lot of bling.” So immediately I thought of the title, “It Don’t Mean a Thing if It Ain’t Got that Bling.” So that’s how I titled it. So to make a long story short those are the shoes that Ronda entered into the shoe show at the Fuller Craft Museum and it got accepted and it went to travel on for two years. Again, Ronda finds on line this Call for Entry, a show called “Shoes: The Perfect Fit” and it’s a travelling show for two years. It’s one of these museum packaged shows that travels from museum to museum. It starts out at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, Massachusetts and it was an on-line thing completely and we got accepted on-line to be in this show. I got it back last September and Ronda entered 3 pairs of high heels in a shoe show in Sebastopol and those were the shoes, so they traveled again.

And that pair of shoes was the first piece of art that I shipped. I built this beautiful crate with foam and wood, this shipping crate to go back to Boston. And it was amazing, it came back the same way I shipped it. I was really proud of my shipping crate. I really did a good job on that crate. That’s the end of the story.

And that pair of shoes was the first piece of art that I shipped. I built this beautiful crate with foam and wood, this shipping crate to go back to Boston. And it was amazing, it came back the same way I shipped it. I was really proud of my shipping crate. I really did a good job on that crate. That’s the end of the story.

Peggy: And now you're doing corsets.

Larry: Oh I’ve got an interesting story on the corset too if you want to go into that. One thing begets another. There’s an artist in her late ’80’s or early 90’s, she’s a glass artist and I admired her stuff whenever I came to town when we vacationed here. Her name is Ina Mae Overman and she did the glass panels that were always hanging in the art museum and she also had them in the mall over the Just Looking Gallery, they’re all over the windows, that’s Ina Mae Overman. She was an engineer

with the Department of Water and Power and she retired and moved to the area, in Arroyo Grande. I noticed that she and Bob Kerwin, engineers, think symmetrically and geometrically. And it’s beautiful stuff, you can’t go wrong with symmetry. It’s automatically balanced. It’s perfect you know. So ok, you can’t go wrong, so one day she did this piece that was different. It had an organic shape, a curve, but still symmetrical so it had a bunch of lines that went up like this, it had some dimension to it. But she had it hanging this way (horizontally), so when I saw it I went like this (tilts head) “That looks like a corset.” So it was like $85. I wanted it to remind me of the corset so I bought it and I switched the wire and I hung vertically. So I decided to make some corsets. I just liked the idea. And I was trying to figure out what to use for the cups, and I said cups, cups, cups, coffee cups, TEA CUPS! Tea cups are fancy, so I decided to make a whole corset from tea cups.

So I saw Ina Mae about a year and a half later at some studio visit and I said, "You know I bought that piece." And she said, "Yeah I know." And I said, "You know, it was hanging the wrong way." And she said, "Yeah, I hung it sideways because somebody said it looked like a brassiere!" And I’m thinking that’s the whole point, what’s wrong with that! So I made a corset. I previewed it for Open Studios. I didn’t know how it was going to be accepted, I just didn’t know. Of course, the reception was great, everybody loved it, they thought it was funny, they laughed because instead of nipples you have love handles. Tea cup handles. And I had two offers to buy it, my first one. And the first one was designed to hang on the wall and I got into a show where they said they had too much 2 dimensional stuff so I made stands for them to make them independent from the wall. So that’s how it evolved. But it evolved from that one piece that I saw. I didn’t steal it, I borrowed it, I was inspired by her, and it just hit.

Michael: And it’s still evolving because back in the studio you showed us the lamps and variations.

Larry: I want to avoid the repetition and I want to do something new to keep me interested so I just kind of kick it up.

Michael: We’ve got one question we always like to end on, and that is what would you tell somebody that’s just getting started? Someone who wants to make an artistic career at any age, whether you’re 19 or 70? And you suddenly realize now’s the time. How do you do it?

Larry: You have to be pragmatic and balance what you want to do with what you need to do. You have to balance it against where’s your food going to come from or how you’re going to pay the bills. So my advice is to know where you want to go and what are you willing to give up to do it, basically. What comfort level do you want? Do you want to be in a relationship with somebody else, you know because it’s a lonely pursuit and it’s selfish. It’s one of the arts you do by yourself. Like writing. It’s not a performing art where you collaborate. And it’s not, when you collaborate like in performing arts you get instant gratification, people like it or they don’t like it and you know it right away. So visual art is the lonely art where you do it alone and you finish it and you put it out there to be reacted to. You want approval, sure, and you want sales, sure, but you do it to feed your soul because you don’t know what else you would do. You know the more you do it the more you think about it too. And I didn’t think about it as much when I was teaching. I mean I saw art all the time and I evaluated art all the time, student art. So I was aware of what was going on but I wasn’t participating in it at the level that I wanted to. A lot of people in this area studied art long ago. They put it down and they're coming back to it because they’re retired and in a position to do it now. We were talking last year to my neurosurgeon. When he retires he wants to go back to that pottery class he took back in college and get a wheel and make pottery, make ceramics. We’re talking brain surgeon here.

Michael: He better subscribe to Outside the Lines! We’re all about getting there.

Larry: Like you say, everybody’s got to find their way there’s no one answer. There’s so many routes to do what you want to do and it’s so true that art imitates life. It’s the life cycle in miniature. You go through trials and errors, you make decisions, you know you make priorities and it’s the same thing in life.

You decide what’s important, what’s not important, what you can do, what you can’t do,

or what you will do or won’t do, who you relate to, who you won’t relate to. All of that, it’s just a miniature scale of imitating life. So those are all the words of wisdom I have. I just do what works for me and fuck the rest!

or what you will do or won’t do, who you relate to, who you won’t relate to. All of that, it’s just a miniature scale of imitating life. So those are all the words of wisdom I have. I just do what works for me and fuck the rest!

Peggy: It really can work.

Larry: It can, it can work on so many levels too. You can do it as a hobby, you can be serious about it. I have a friend who went to art school with me. She’s going to have an exhibit next month in Paso. She’s a water colorist. She’s a great drawer, she drew beautifully out of high school and she was one of these people that thought you go to art school and you’re going to be a famous artist. A few do but it’s just like the acting world. You’ve got the superstars 1% at the top and all these hungry people at the bottom trying. And then you’ve got to know or decide when to quit trying or when to settle or when to find your level or your fit. I never wanted to go after fame for fame’s sake. I just want to do my thing and have fun doing it.

|

Larry LeBrane is a glass and multimedia artist working and living in Los Osos, California. His studio is in San Luis Obispo, and he's known nationally for his avant garde stiletto heels and tea cup lingerie. What struck us about Larry as we talked to him is that he's one of those artists who consistently made choices that kept him on the artistic path from an early age. As you read through this interview, and look at the images of Larry and his work, you'll get a sense of the infectious humor that shows up in everything he does. Let's jump right into the interview.

Larry LeBrane is a glass and multimedia artist working and living in Los Osos, California. His studio is in San Luis Obispo, and he's known nationally for his avant garde stiletto heels and tea cup lingerie. What struck us about Larry as we talked to him is that he's one of those artists who consistently made choices that kept him on the artistic path from an early age. As you read through this interview, and look at the images of Larry and his work, you'll get a sense of the infectious humor that shows up in everything he does. Let's jump right into the interview.

drafted and it turned out to be a great experience. I just spent two years in the Army. She taught art for the Army for special services. She had a GS-7, which is the equivalent to an officer, like a Captain or Lt. or something like that. We ate at the officers’ club, we lived off the base, we were in Korea during Vietnam. It’s kind of funny too because they trained me for computers. So here I had an Art degree and my masters. I went to Army Adjutant General School for computer training. And in those days it was collators and punch cards so they ended up sending me to Seoul, Korea, 8th Army Command. It was a great job. I had a night shift. We had a Korean maid. We lived on the economy and it turned out to be great. And we would take leave to Japan for 2 weeks. We slept at Army bases, saw a lot of the art. We studied Japanese history, art history. We went to Kyoto, Nara, Tokyo of course. We went all over Japan. We rode the bullet train. This was a culture shock too because in those days, this was ’66 to ’68 and Korea was underdeveloped. It was like Tijuana, so to go from there to Japan was a big shock. Japan was into their tech boom. It was kind of like going from Tijuana to San Diego. It was weird. It turned out to be a great experience anyway. Then when we came back I got a computer job on graveyard shift. Meanwhile I applied for teaching because I wanted to use my degree. I got a job in Fontana, back in the Riverside area. It was teaching art, and I was only there a year before I switched to Rialto, which is where my wife was. She had a job teaching art, and the reason I switched was that district didn’t give me credit for my simultaneous degree. In other words I got a bachelors and masters at the same time and they didn’t recognize it. Some districts recognized it and some districts didn’t. So I just moved.

drafted and it turned out to be a great experience. I just spent two years in the Army. She taught art for the Army for special services. She had a GS-7, which is the equivalent to an officer, like a Captain or Lt. or something like that. We ate at the officers’ club, we lived off the base, we were in Korea during Vietnam. It’s kind of funny too because they trained me for computers. So here I had an Art degree and my masters. I went to Army Adjutant General School for computer training. And in those days it was collators and punch cards so they ended up sending me to Seoul, Korea, 8th Army Command. It was a great job. I had a night shift. We had a Korean maid. We lived on the economy and it turned out to be great. And we would take leave to Japan for 2 weeks. We slept at Army bases, saw a lot of the art. We studied Japanese history, art history. We went to Kyoto, Nara, Tokyo of course. We went all over Japan. We rode the bullet train. This was a culture shock too because in those days, this was ’66 to ’68 and Korea was underdeveloped. It was like Tijuana, so to go from there to Japan was a big shock. Japan was into their tech boom. It was kind of like going from Tijuana to San Diego. It was weird. It turned out to be a great experience anyway. Then when we came back I got a computer job on graveyard shift. Meanwhile I applied for teaching because I wanted to use my degree. I got a job in Fontana, back in the Riverside area. It was teaching art, and I was only there a year before I switched to Rialto, which is where my wife was. She had a job teaching art, and the reason I switched was that district didn’t give me credit for my simultaneous degree. In other words I got a bachelors and masters at the same time and they didn’t recognize it. Some districts recognized it and some districts didn’t. So I just moved.

And that pair of shoes was the first piece of art that I shipped. I built this beautiful crate with foam and wood, this shipping crate to go back to Boston. And it was amazing, it came back the same way I shipped it. I was really proud of my shipping crate. I really did a good job on that crate. That’s the end of the story.

And that pair of shoes was the first piece of art that I shipped. I built this beautiful crate with foam and wood, this shipping crate to go back to Boston. And it was amazing, it came back the same way I shipped it. I was really proud of my shipping crate. I really did a good job on that crate. That’s the end of the story.

or what you will do or won’t do, who you relate to, who you won’t relate to. All of that, it’s just a miniature scale of imitating life. So those are all the words of wisdom I have. I just do what works for me and fuck the rest!

or what you will do or won’t do, who you relate to, who you won’t relate to. All of that, it’s just a miniature scale of imitating life. So those are all the words of wisdom I have. I just do what works for me and fuck the rest!