The Windhook Interview—Randy Stromsoe

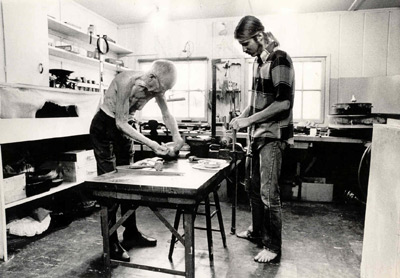

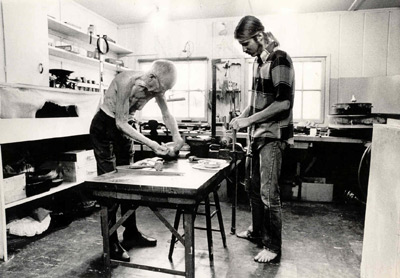

We interviewed Randy at his studio in the Santa Lucia mountain range between Cambria and Paso Robles Ca. Half way through the interview we were joined by Randy's wife, Lisa. It became clear immediately what a team they have been over the years. It's a jam-packed interview, so let's get right into it.

We interviewed Randy at his studio in the Santa Lucia mountain range between Cambria and Paso Robles Ca. Half way through the interview we were joined by Randy's wife, Lisa. It became clear immediately what a team they have been over the years. It's a jam-packed interview, so let's get right into it.

Peggy: Where did you grow up?

Randy: San Fernando Valley, Panorama City.

Peggy: Was anyone in your family involved in art when you were growing up?

Randy: No but I was an artist as a grammar school kid and in junior high school I was the one that would do the murals and enter the art contests.

I showed some artistic promise so they kept pushing me. But as a kid I was thinking you don’t make any money as an artist—And I was good at math so I thought the art thing was kind of silly. But then in junior high they had some craft workshops where you had plastics and you got to laminate them and carve them and shape them and polish them and create all this stuff and I found that fun.

Peggy: So where’d you go to college?

I went to LA Valley College. They had a handful of really talented teachers. The second semester I took the crafts workshop. I thought I’d be making tables. I had no idea it would be jewelry and metalsmithing.

Michael: So you thought it was woodworking?

Randy: Yeah, it was called Crafts Workshop and it was jewelry and metalsmithing. And at that time time jewelry was really taking off. Full classes and waiting lists. They had two classes—advanced and beginners at the same time in a big room. Once I found out we weren’t going to do tables and things, I really wanted to drop it but I didn’t know how so I stayed in and had a good semester where it really clicked for me. I remember I sold my first piece that semester. We had a student show and I sold a belt buckle. That seemed kind of exciting— the first piece I turned in. It was one of those ah ha moments.

I didn’t know I was ever going to find anything in life I could do better than anybody else. So when I turned in my first piece and the teacher said, “Uh oh, we have a craftsman here,” that was nice. This teacher was Zela Margraff. She would enter competitions in London, Germany, and France and come in 2nd or 3rd. She was in her 60’s and she was tough and scared people off but she was really a sweetheart.

Michael: You were 19 when you started to work for Porter Blanchard. That must have been around this time.

Randy: Yeah. She had a field trip to Porter Blanchard’s shop. There must have been 30-40 students there.

We pull up, and Porter’s out there, dress slacks, dress shoes, and no shirt. He was real excited to show us everything. You walk into his shop and he has his father’s tools and his uncle’s tools—it was like stepping back 100 years. He had all these wood forms and leather forms and anvils.

Peggy: where was this?

In Pacoima, off Laurel Canyon Blvd. He had 10 acres, orange orchard, boat shop, chicken coops, a couple of houses and swimming pools, and when he died we were making a boat. He was 84 but he didn’t know he was 84. He didn’t look in the mirror much. He just got on with life and he liked young people because they’re full of life. So he was raising an oval vegetable platter and he had some of us try it. After I got done he came up to me and said, “How about coming to work for me.” What he didn’t know was I was the only person in the class that had tried the technique, so before this, I had already mutilated a couple pieces of copper and couldn’t seem to make it work. But when he was explaining it to us I had one of those moments—oh! now I know what I needed to do. Those other guys didn’t have a chance.

Michael: So that was your big break.

I knew this was a big opportunity in my life. I asked if he paid and he said, “yes, I pay.“ Zela was trying to get me hooked up with her master and that wasn’t a paying job. You had to pay him $3000 a year and you had to go there and pay your own room and board and pay him for 3 years, the 4th year was free and the 5th year he paid you. So four years without any pay and I looked at her and she looked at me and said, “You’re pretty lucky.” So I jumped at it.

How many 19 year olds get to butcher a piece of silver and stamp their master’s name on it and have people buy it? You know I went back a year or two later and looked at some of the pieces I made for some of the stores in Westwood and Beverly Hills and some of them were terrible. You cannot become a master silversmith in your first couple of months. You have to pay the price. You’re not going to be doing quality work that quick.

Peggy: So Porter died when?

Randy: Somewhere around 1973.

At the end Porter was in the hospital. I was his bookkeeper and I was getting these ideas, and we made up all these new products. We changed what people were doing. We went down some bad avenues, but we were young—we didn’t know. We did some real time consuming pieces, that had hammer marks, bright polish, handmade handles, some chasing and fluting and real cool wrapped things. They were selling and we were making good money. Then all the companies on the East Coast—Reed and Barton and others started copying us. They’re copying this Porter Blanchard Company stuff. They think it’s this old master making it and it was just these 20 year old guys. We were shaking things up, taking chances.

Michael: I want to dig into the concept of apprenticeship. Does it have a place today?

Randy: Well, yes and no. Realistically, an art organization or program of some kind should be paying the artist to have an apprentice. In most cases, at the Porter Blanchard Company when I was there I worked with maybe 20 different workers and I don’t think any of them are silversmiths now. All of them had good potential but most of them get a few years behind them and want to go out on their own. So you’ve been paying them while they’re learning and they’re messing up everything that they do, so you’re losing money and then they finally turn around and leave.

Peggy: Some countries have sponsored programs where you go work with a master—scholarships, or fellowships.

Randy: Seems like in this country we’re down to a handful of people who know these skills. We need apprentices. And we have university programs, but we’re losing a big step. And the only way I could do it is if someone payed me. I was amazed that Porter paid me as much as he did. But at that point any thing he turned out people would buy and we had a waiting list of orders. So it was a little easier.

My teacher, Zela Margraff always got different apprenticeship grants and it didn’t cover the whole price but she’d show her body of work and her apprentice’s body of work. She’d teach and get like a $10,000 grant. I know with the internet now you can find out more about things coming up than you could 5 years ago. I have everything set up. I have it set up like the old shops did. I just need an open mind, somebody that can take it all in.

Peggy: How have things changed?

When Porter was my age he was dealing with a handful of families that were buying everything he made. 15-20 years ago my customers had a list: a water pitcher, a coffee pot, a creamer, an ice bucket, serving pieces, candlesticks, a vase, some big bowls, and some salad bowls. They didn’t get just one piece. If you got a customer, you got a customer for years to come. Nowadays that doesn’t exist.

A lot of the connoisseurs, a lot of the collectors, a lot of the museum people don’t know how to appreciate silver. You can see that with appraisers, like on Antiques Roadshow—silver is always way down there. People think that the sleek and unadorned images are simpler to make but in a lot of cases making something simple and elegant is as much or more work than a lot of decoration. There’s a lot of craftsmen that wouldn’t be able to make a sleek piece. There’s some people who really know what they’re looking at but the appreciation of everything’s really gone kind of crazy.

And now in the jewelry industry they’re figuring out all these gimmicks and instead of hammering out a piece you could have this device do it, and if you get enough equipment, you can make a lot of products without much craftsmanship. And they sell the metal clay now, a clay they can put in the oven, 500 degrees and it comes out metal. It doesn’t take any craftsmanship. It’s getting to be more a hobby thing. In the old days to be a silversmith took 5 to 7 years.

Michael: It seems like this is another example of how the modern economy has moved away from the old ways. And what I hear you saying is there are no shortcuts. Maybe there are shortcuts but you end up with a different result.

Randy: A few people that are doing it right are gaining really good recognition. In Europe it’s a lot better. But there are Americans and also some Europeans who are working with their hands on thin pieces of metal and they’re forming up to forms and they’re repousseing and chasing it and overlapping and gold leafing on the inside stuff and they’re wonderful and they’re little pieces like that. if you take a picture of it it looks like sculpture. Beautiful stuff, and they’re mastering the skills and they’re getting some recognition.

Things I used to do when I was a young man are coming back into fashion so it’s kind of exciting for me because I can go back and retrace some of those ideas and get back into it and maybe fall into the European direction.

Peggy: Where do ideas come from?

Randy: In just the last 2 months I probably have 100 drawings. They’re all concepts. A lot of the things I do are like prototypes. I can make them in pewter relatively quick. The final piece may be in copper or silver later but I’ve got to get the idea and the form out and when I get the form out and look at them, things evolve.

[Randy’s wife, Lisa enters the room.]

Michael: Let’s talk about your gallery, Quicksilver.

Lisa: That would be me. Before Quicksilver we started another gallery in Harmony.

Randy: We got this great deal to have a shop there, utilities included, $100 a month.

Lisa: It was 1980. So we formed a partnership with Hallie and Stan Katz from Ojai and they would come down and actually sleep in the Creamery. We had a really big space and super avant garde stuff—stuff you wouldn’t even see in LA or New York. Totally off the wall stuff and a lot of people didn’t get it. There were a lot of people moving here from LA and San Francisco. At that time there was no art in the area except the Art Center.

Randy: We also had a lot of local people coming to Harmony. We had one opening and there were cars parked everywhere.

Lisa: It will never happen again. Artists were just mellow, communal, trustworthy, honest. Special, special time. And then I got pregnant. There wasn’t enough money to support two couples. So Stan and I scouted out Cambria. There was a little place for sale. So we bought it and opened Quicksilver. Quicksilver ended up being a pretty amazing gallery because we got on the radar somehow with the American Craft Council. You know Randy was definitely involved but Randy was making product and we had a little kid at that time and we thought we could kind of raise her in the gallery environment, which didn’t really work out well. Quicksilver was my glory time. When I look at that time I think that’s what I’m most proud of other than my kids.

Randy had been in the White House and they came to me and said we want you to be a juror for Baltimore and San Francisco. We’ll fly you to New York and from there we went to Rhinebeck and I asked, "Can I bring my husband?" "Well we don’t normally allow for spouses." So I’m sitting there jurying with these big wig people and he’s tootling around with these women checking out the sights. It was really role reversal. It was really wonderful. I gleaned a lot of knowledge from that 3 day experience.

Quicksilver lasted till 1991. Great gallery, great time, but open 10:00 a.m. till 10:00 p.m. 135 artists, 6 employees and we had our daughter Nichole, and then I got pregnant with Sean. He was born in May and it was like April 5 and I said I don’t think I can do all this. We had a kindergartner and this baby coming and 11 years of gallery stuff so we sold it.

Peggy: So how did you get to the Reagan White House?

Lisa: We kept seeing this ad in Metalsmith Magazine. “Silversmith wanted” and listing all the things they wanted the silversmith to do— contact Colonial Williamsburg.”

After about a year, we answered the ad. We didn't have a typewriter, so in my little handwriting, "Dear Colonial Williamsburg, my husband ..."

He had a phone call three days later and was on a plane within a week—from that silly little two page handwritten letter.

Randy: They hired me as a designer/craftsman and a master silversmith and after being there a week they gave me a raise to the top of the pay scale. Then they asked me to form a whole new department. I asked if that meant a raise, and they said they already gave me a raise and they couldn’t give me another raise again ‘til the next year. So you want me to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars, set up a whole dept and work for craftsmen’s wages, hmmmm, it doesn’t sound like you really want me.

But at Williamsburg I worked on a silver letter box for the President of France, a dozen tankards for the mayor of Paris, and paperweights and stamps. I worked with the violin maker George Wilson at Williamsburg, a really incredible violin maker but when he got the opportunity to work on some silver with me he got all excited and we’d work ‘til late at night and we talked a lot. He said, “Randy you have a shop in California. Don’t stay here. It’s like being in the military. They give you enough money to live and the encouragement, but you can’t really get ahead. If you get a chance to be on your own, just do it.”

We had some good projects there but we really couldn’t wait to get back home. We had a chance to meet Reagan and Bush at the White House. It was one of those things where you go deliver the work and you can hang out and see if you can meet them. We didn’t have an appointment. We did meet George Bush and they told me he really liked the tankards.

Michael: How you balance the creative work with family.

Lisa: It’s a dance.

Randy: Not that well.

Lisa: No it was never bad but it was intense.

Michael: But you guys seem like a really solid team.

Lisa: I don’t make the silver part at all. I don’t do any of what he does and he doesn’t do much of what I do. When we were really in the business of doing shows, I’d pack the boxes, wrap the stuff, do the inventory, call the trucking company, send in the money. And he did his Mr. Mom stint for sure. Nichole was a rascally little kid and he would have kid duty when I was at karate and I’d come home and she wouldn’t be in her pajamas and he’d have a thousand barrettes in his hair.

Randy: But I had dinner made and everybody’d be ready and the kitchen was clean and food was made.

Lisa: It wasn’t dysfunctional.

Lisa: He was definitely not an absent father. He did his stuff.

Randy: I coached at Santa Lucia with the kids so I did my sports thing and played ball with them.

lisa: Kids in school and kids in sports. We took the kids to the Smithsonian and to Washington DC with us and did a show. Sean is deaf and he had a tutor, like a speech and learning tutor, so we hired her to come with us to DC. We just paid for her ticket and she spent time with the kids. We have darling pictures of the kids in suits, they grew up at all the craft shows.

Randy: Nichole would say “Dad, people are touching your teapot.” “Dad, they didn’t buy your bracelet.” And she’d say it right in front of them.

Lisa: And they’re both artists.

Randy: It was kind of fun meet other artists and meeting their kids and have the kids meet their kids. I think the whole creative thing was pretty fun that way. It’s hard. I’m aware that the most successful artists don’t have kids. If you want to be really successful you don’t have kids the ones that are most recognized don't have kids and their contemporaries that they’re neck and neck with that have kids, that do nice work, they aren’t recognized in museums and things as much.

Michael: but I guess that’s just—ok.

Lisa: we feel so blessed that he’s never worked in another job, ever, since 19. Not in a restaurant, even the best actor in the world worked in a restaurant or parked cars.

Randy: But I do have lots of skills that saved us money, like building and stuff. I built the house.

Michael: Have you ever questioned it, wondered if you took the right path?

Randy: Oh yeah.

Lisa: If he had been a university professor, he’d be retired right now.

Randy: But yeah, even if I had worked at Martinez and Company, it might have been a partnership we could have done, but I just really didn’t want to live in LA and suburbs, I couldn’t drive the freeways everyday. The companies that we had opportunities with were never really where we wanted to live.

Lisa: He was going to go work in Barbados, but I was pregnant with Nichole and the grandparents were all still alive and they complained about not being able to see her.

Michael: It just seems like a lot of people who do choose to have a family end up getting derailed from an art career.

Lisa: They do.

Michael: I think it says a lot that you’ve gone all the way through.

Lisa: Our kids are his biggest fans. And when he wasn’t as prolific, like when he was building the house, and they were always bitching and moaning at him, like get down there and make jewelry, get down there. He had support from his family. With some families it might be “Dad, how come we can’t afford an iPad.”

Randy: And we had a family but we also had to take care of family. Lisa’s the oldest in her family and I’m the second oldest in mine and with Lisa’s family she had three sets of grandparents to take care of.

Lisa: My Dad died at 52 and my mom died at 66 and she died before her parents so I had to take care of her parents.

Randy: So we've taken care of elderly people a few times. It made for a lot of driving and a lot of hanging out and going down south so it made for a really disruptive life for us. It was really hard to raise kids, keep the gallery going, make artwork and do shows. You’ve got a lot of money tied up to do a show. To bail on it is hard.

Peggy: And they were out of the area shows.

Randy: We tried to do good shows on the East Coast. You send slides in and you have to be chosen. We lucked out, at one point, after the White House stuff. I only did the Baltimore show once and through that show I met buyers like the buyer for MCI world headquarters collection and Michael Monroe. And Mike Monroe was a guy to meet because he was the guy in charge of putting the White House collection together. He was the curator of the Renwick at the Smithsonian. So from one show we met the most valuable guy and he kind of kept an eye on us and he asked me for different images of different pieces at different times. We did our best to keep up with him.

Michael: This sort of sounds like an example of the old adage, that luck is the intersection of preparation and opportunity.

Randy: Yeah, preparation and putting yourself out there. You have to get out there and take your chance on the luck happening.

Lisa: Yeah—Like writing the letter to Williamsburg. I was afraid they’d think I’m silly— that handwritten letter's not very professional. I was 19 and just did it without a typewriter.

Randy: I saw something in a book about tabletop art and sent some pictures in for that. We went to Franz Bez and had some pictures taken. We’re pretty darn young and green and we sent these pictures in and sure enough it made it into the book, in fact the back cover of the book. And important people see that and all of a sudden things are working out. That whole thing with the Year of American Crafts in 1993 and '94 was pretty wonderful. I was invited back to the National American Museum of Art where they were having a show of White House pieces. I was supposed to go back there and meet the First Lady and they wanted me to come back and do a walk through and all that. It was a big hall and there was one room 15’x15’ and there’s one pedestal and there’s my one bowl in the middle of it. The only thing in the room. And they’re treating me like a celebrity. I was supposed to have a photo session with the First Lady. It was a pretty crazy and wonderful day and they interviewed me. And the First Lady comes up to me and says she has to go. It was the Oklahoma bombing and she couldn't stay, so the whole thing was taken away. So I go home and the Smithsonian says we’re going to do a Year of American Craft in 1995 and you’re going to be the featured person. You’ll get a booth front and center in a special part of the Smithsonian and you’re going to come here early and you and the First Lady are going to do a walk through. And this is off the charts, and I can’t believe this is happening. I hire this guy and we’re packing it up and we work on this for 6 months. Lisa has to pack it up, it’s backbreaking, weigh each one and the truck comes. Off it goes, and theoretically you get on a plane five days later.

Lisa: Ring a ling, "There’s a teamsters strike and your work is in Ohio at the hub station of the Teamsters and you’re SOL." I called the police, and the sheriff—my husband is coming back there to get his stuff, we wanted to get a uhaul and they said you can’t. You won’t be safe.

Randy: They used the images for the publicity for months and they gave us the best spot—150 artists. And they said, “Randy, no one’s ever cancelled on this show.” And I said, “What do you expect me to do?”, and they said, “Come back with a scrapbook and then sit at this table with the scrapbook.” And this was before computers and we do highly reflective material and we didn’t take pictures of too many things because it’s so hard to be photographed, so we were having everything professionally done. We had to spend so much more 20 years ago, because now with digital photography you can fix things. It was a thousand dollars or so every time we took an image and that was a lot of money.

Michael: It almost sounds like when you hear the First Lady is going to be involved you should just run the other away.

Randy: But you know she was on the CBS morning show and she was talking about the pieces and she took a tour of the White House collection and she had Dale Chihuily and Clifford Lee and she’s talking about the Chihuily bowl and she’s talking about the Randy Stromsoe bowl. And the last couple sentences she’s talking about my work and Chihuily’s work and that’s how the show ends. That worked out really well for me, we didn’t know it was going to be on.

Peggy: There was a picture of you with the Clintons.

Randy: That was '94. Lisa had to make me go. We’re getting to do shows, to do exhibits and I have work, like 50 pieces, halfway done.

Lisa: We get a thing in the mail, regular mail. We get the Blue Cross bill, the PG&E bill. Oh there’s something from the White House. I open this up, the President and Mrs. Clinton invite you to join 35 artists. Please contact Ann Stock, the social secretary.

So I called Ann Stock from my sister’s house in Los Osos. They didn’t pay for anything, no taxpayer dollars were spent. We donated the bowl, we flew back on our money. We came for the party.

Randy: I said we can’t afford that.

Lisa: I forced him this one time. And everyone was there and it was a huuuuuge deal. It was amazing.

Michael: It seems like you’ve had some amazing promotional opportunities.

Lisa: That one White House bowl image that we had taken has gotten us probably ten years worth of advertising. It was shown everywhere. We always go to our guy Ron Bez. He always uses the same backdrop so it’s all consistent, so if you saw 5 images on the wall, it all goes together. That’s huge, we learned that pretty early on.

Randy: I study the piece for a few weeks to decide how it should be photographed. The photographer just wants to get that camera and zoom in. So I’m hands on with photography. I think it’s better if you do this, just trust me it’ll be better if you do it this way. We get the million dollar shots other people who photograph the same bowl don’t. Like the White House bowl, the White House photographer didn’t get it right.

Michael: Have you ever blown an opportunity?

Randy: The only time I said no to somebody was probably the biggest mistake in my life. We had our motorhome packed and the kids in it and we were out the door heading out for vacation. We drove around the block and I had to come back for a few things I forgot. I answered the phone and Kenneth Trapp of the Oakland Museum was on the phone. He said, “Hi Randy, I just thought I’d get your bowl for the 50th Anniversary of the Oakland Museum. It’ll be the one commissioned piece we buy. I’m coming down right now to get it.” I said, “It’s not a good idea. We’re just leaving. I’ve got a motorhome and we’re going to be gone for a couple of weeks. Can we do it in two weeks?” He said, “That’ll be fine. We’ll do it in two weeks.” I never heard from him again.

Randy: And I look at that like if I had that piece as the 50th Anniversary present of the Oakland Museum that would be a major collectible piece that would be worth 100s of thousands of dollars that would cement me into something much bigger than I’m cemented into now. He did get a couple of pieces for the Oakland museum for their jewelry collection. And he did make sure that he wrote about them and that people at Metalsmith published pictures. He was a good guy, and a good guy to have in my back pocket, but he retired. So that’s one of those things, don’t ever say no, don’t say maybe, say, “I’ll be there, you can count on me.” Next time, next time...

Peggy: To follow up on the photographers, is Ron local?

Randy: Yes. Ron Bez. His dad was Frank Bez, a New York photographer. We found him by looking at American craft magazines. And right off the bat we had him take pictures and made a book, we got into shows. We never got excluded from a show because of the photography we had done. And quite often we got the photos used for the show.

Lisa: It was hard in the early days, we were really poor for real, but we knew photography was important, we gave ourselves that.

Michael: What’s next? I’ve heard you make comments about doing some things that are a little different.

Randy: I’ve worked 40 years to get to this point where I actually own all this stuff and I don’t have to keep paying on things and I can start making art. I don’t have to panic about money coming in as much as in the past. In the past I had to have a cash flow coming in. It’s a pretty nerve wracking type profession to especially try to grow, to take chances. But we do have a lot of pure sculpture that I want to do and there’s some commentary and political things that I’d like to do. And I guess I’d just like to explore.

Michael: Just as an example, the masks that you’ve been doing lately are very interesting. Is that new to you or have you always done that kind of thing.

Randy: I think it’s been several years with the masks. 5 years, but it’s taken me a long time to take them seriously.

I have ideas for sculptures I’d like to do where I could do the shoulder blade and connect them up with some forging and rods and connect them so you have a silhouette but it’s not a whole silhouette. I like what Michael Hannon does with the torso. We used to hammer out torsos. Porter did some torsos. And I think Michael’s torsos are better than what Porter did, Porter’s didn’t have so much life to them and Mike’s really do.

Michael: Yes he has quite a collection of them and he’s really good.

What would you tell somebody that’s just breaking in and trying to make an art career happen?

Randy: I think I’d find what show fits your work. It’s easy to get excited if you have an arena where they like your work and you’re a celebrity. If I just tried to make it in Cambria or San Luis Obispo, I would have been so frustrated. If I never took a chance and went to the East Coast then my life wouldn't have worked out. You have to find these arenas and so much of it is word of mouth by talking to other artists and looking at their brochures and what work they’ve pushed before. In California there are a few good shows like Sausalito where people can get good exposure and meet the right people and sell thousands of dollars of work. Scottsdale might be a good show. Some areas sell a lot of what we do. If I go back to Philadelphia to the Museum of Art Craft show I have more buyers than anywhere else. They also promoted me more than anywhere else. That show has been really good to me and the people who go to those shows have bought a lot.

|

We interviewed Randy at his studio in the Santa Lucia mountain range between Cambria and Paso Robles Ca. Half way through the interview we were joined by Randy's wife, Lisa. It became clear immediately what a team they have been over the years. It's a jam-packed interview, so let's get right into it.

We interviewed Randy at his studio in the Santa Lucia mountain range between Cambria and Paso Robles Ca. Half way through the interview we were joined by Randy's wife, Lisa. It became clear immediately what a team they have been over the years. It's a jam-packed interview, so let's get right into it.