The Windhook Interview—George and Beth Kendall

Most of our interviews are with people in the arts, but as you know, we are interested in anyone who is making their own path. George and Beth Kendall are our neighbors, and they have certainly forged their own path. Geologists by training and profession, they retired early from careers in the oil industry to grow citrus and avocados for the regional produce market. You will notice a certain similarity between the challenges that they face as farmers and the challenges that other entrepreneurial free spirits must meet and overcome.

We have known the Kendalls as long as we have been on the central coast, and they have been on the short list of potential Outside the Lines interviewees since the beginning. We think you will enjoy this conversation, and if you are like us, you will learn a few things you didn't know.

Peggy: Let's start at the beginning. Tell us a little bit about where you grew up. Beth, you can start.

Beth: I grew up in Connecticut. I was one of four girls. I was educated at public schools up until sixth grade, and then in seventh grade I went to a private girls school for six years. In college I majored in geology. Then I went off to graduate school in Oregon for a masters degree in geology, and that's where I met George.

Peggy: What made you choose geology?

Beth: I chose geology because I was really interested in doing a science. I didn't think that biology would work for me. Chemistry definitely wouldn't, so really I backed into it, but really enjoyed it. It does take you outside. It was a nice fit for me.

Peggy: I can see that. Chemistry would be in a lab indoors.

Beth: No, I liked being outside, and I liked hiking, and I do like rocks and gems and minerals.

Peggy: And George?

George: Well, I grew up in Southern California, in Escondido. I was one of four boys. My father was a commercial fisherman and various and sundry other things. We grew up in a fairly small town. Part of the time we lived on a small farm, but most of the time in tract housing. I went to public school straight through. I went to junior college one year, went to UCLA three years, and on to graduate school at Oregon State where I met Beth. I started my college education as an economics major but didn't really like economics, so I switched to geology when I transferred to UCLA as a sophomore.

Peggy: Why geology?

George: I guess there's a little history to that. When we were kids we belonged to the Palomar Gem and Mineral Society, and we went on lots of rockhounding field trips, so I was aware of it. This was like many, many camping trips. And my father gave me a book on California geology when I was in high school, just because I showed some interest in it I guess. It was a kind of professional publication. I didn't really think much about it, but took an introductory geology class at Palomar College, and liked geology. Meanwhile I transferred to UCLA as an Econ major but in the process of all those changes, decided that I would switch to geology. So I sort of backed into it based on interest, and the realization that I didn't like economics.

Michael: Tell us more about how you met and how that ties into your careers.

Beth: Well, we met because we were in the same department, and it's a pretty small graduate department. How many students do you think there were? Maybe 20?

George: Yeah, I think there were about 20 masters students and maybe half a dozen PHD candidates.

Beth: We were all in one building on two floors, so we were all together.

Peggy: George, what was your particular area of focus in geology?

George: Fairly early on at UCLA I decided that the place where the jobs were—remember, this was the early seventies—was petroleum. That was soft rock or sedimentary geology. So if you learned stratigraphy, sedimentation, those sorts of things, you could find work in the oil industry, as opposed to mining, which would be hard rock geology, which is a whole lot more cyclical. So I was looking at having a job.

Peggy: And Beth?

Beth: I wasn't looking at it that way. For me the work that I did was related to which professor I liked the most and felt the most rapport with. I ended up doing a project with a professor that I liked, and my project was more related to tectonics. In the end, I went to work for an oil company right out of school, and they were taking any geologist. What your specialty was for your masters wasn't really a strong point with them. They were going to be training you anyway.

Peggy: Did you both finish at the same time?

George: I was a year ahead of Beth. I finished all of my coursework and the field work for my thesis in the summer of 1974, and got a job and actually defended my thesis in the Spring of '75, and you finished...

Beth: In the Spring of '75.

Peggy: And you went to work for...

George: I went to work for Standard Oil Company of California. Chevron.

Peggy: I still call it Standard.

George: In San Francisco. That was pretty exciting. Big city.

Peggy: How big was Escondido? You said it was small then.

George: Escondido through the sixties was one of the fastest growing towns in the nation. When I was born in 1950 it had a population of about 5,000. By 1960 it was about 16,000, and currently has a population in the range of 100,000. So it was going through tremendous growth, essentially a suburb of San Diego. San Diego was growing a lot. So there was a lot of change there.

Peggy: Beth, give us the sequence. You finished your masters...

Beth: I finished my masters, and we had decided to get married. I had a job in Bakersfield with Union Oil Company. We tried to figure out how to get jobs in the same place. So I went and talked to Chevron. George had arranged for me to have an interview at Chevron in San Francisco. The only other company in San Francisco was BP and they did not have a reputation or policy to hire people fresh out of school. They hired people with experience. So they weren't an option for getting a job. I went for an interview at Chevron and was told that they didn't hire spouses, period. This was when women were just getting into the industry and policies had not been put in place yet that allowed them to deal with couples. So the way they were dealing was just to say no. No couples. In the end, George quit his job with Chevron. He asked for a transfer to Bakersfield and they wouldn't do that either. So in the end, he quit his job and moved to Bakersfield where there were far more opportunities than there were for me to work in San Francisco in the field. So we settled in Bakersfield.

George: Indeed, we did.

Peggy: How long were you in Bakersfield?

George: We moved there in '75. I remember driving to Bakersfield. It was hot. A hundred some odd degrees when we drove there. The first time we lived in Bakersfield we were there until 1984, so we were there for nine years the first time.

So I quit Chevron, got a job with a drilling fluid company—a mud company, and left Chevron on Friday and started work there on Monday.

Peggy: They call it a mud company?

George: Drilling mud. It's the fluid that circulates the cuttings out of the hole and cools the drilling bit. It's kind of a service job. It's what blew out in the Gulf of Mexico.

Beth: It keeps the pressure under control theoretically—the weight of the mud. But George worked there for a year, and then he got another job as geologist for a small company, and then he got another job after about a year with another company, but still a small one, relatively speaking in Bakersfield. That company was bought out by Shell, and he worked for Shell for a little while, and then went on to Occidental Petroleum. And this was a measure of how George operates. He needs constant change. Or challenge would be a better way of putting it. And Oxy finally gave him that challenge that he was looking for. His job really varied, and he could tell you more about it than I can, but I'm leading up to the fact that this is why farming is such a good fit for George because it's constantly challenging and constantly changing. So it's a new problem every day.

George: The mid to late 1970s was a really dynamic period in the oil industry. We went through the Arab oil embargo and the Iranian oil crisis, there were lots of job opportunities. Drilling activity was high, oil price was going up, economics were good. So it was relatively easy to find employment and to try to find your right niche. Milchem was kind of a service company, focused on drilling operations, but what I really wanted to do was geology. So I went to a small company called Teal Petroleum. We developed heavy shallow oil. Then I moved on to Belridge Oil Company, which was a very active drilling company, again heavy oil and fractured shale production. A lot of activity but underdeveloped. And it was purchased by Shell which then put a lot of money into it and really expanded production.

Peggy: Is Shell actually Dutch?

George: Shell is actually Anglo-Dutch. It's owned by both British and Dutch interests. But I didn't like working for the giant oil company, so when I had the opportunity to work for Occidental, I jumped at it, and didn't look back.

Peggy: You were with Occidental for how long?

George: I think 20 years. I started there in 1980, and I loved it. They gave you as much responsibility as you could handle, and gave you lots of different projects. But I formally left Oxy at the end of 2000.

Peggy: Was that Hammer?

George: Armand Hammer was the chairman, or president. I can't remember exactly, but he was the head of the company. It was a publicly traded company.

Michael: Beth, did you work for Occidental at some point?

Beth: No. I ended up working for Union Oil for three years. I was not particularly happy in the oil business. We moved around in Bakersfield and we finally bought a place in east Bakersfield that had ten acres, five acres in citrus. So we started dabbling in farming at that point. Then we bought some greenhouses on the other side of Bakersfield, and were growing hydroponic tomatoes. So I started doing that full time. During that time both Scott and Eric were born. So they were babies in the greenhouses. Eventually we sold those and I did go back to work on an hourly consulting basis. At first it was ten hours a week and it worked itself back up to about 30 hours a week when the children were toddlers. George then was transferred overseas, and that was when I stopped working all together, because our visas wouldn't have allowed me to work in the countries we lived in overseas. It was a good time for me to be home with the kids full time, because they were in grade school. So it worked out well.

Peggy: I wanted to go back to the citrus. George, when you grew up in Escondido, that area had a lot of citrus, right?

George: Yeah, Escondido is in citrus and avocado production country, and the little farm we lived on when I was in high school had a couple of acres of oranges and about six acres of lemons. So I had experience taking care of citrus, and liked it.

Peggy: Obviously, yes.

George: So in our early years in Bakersfield, we decided to look around for a little farm and we found one out on the east side.

Michael: You pretty much always had this farming thing in your blood, and you made a career in the oil industry until time to retire. Was it an early retirement?

George: It was an early retirement. Yes. I worked overseas for ten years, in several countries, and was transferred back to California in 1993 or the beginning of 1994, and then had a job that made me travel to all of Occidental's operations, looking at geologic aspects of production. In 1999 Occidental decided to transfer its overseas technical office from Bakersfield to Houston. At that time I decided to not move to Houston.

Beth: At that time we had already purchased this property.

George: What happened is that in 1996, the exploration department had a team building exercise at the Morro Bay Inn in Morro Bay. One of the exercises was to come up with a vision statement for the exploration department and a mission statement. We were sitting in this dark room wordsmithing these statements, and I thought, "George, you need to have your own vision and your own mission." So my vision was to have a farm, and my mission was to accomplish the farm. That started sometime in '96 and in the summer of '97 we had purchased the farm.

Beth: We looked for a year, so from that time to when we found it was about a year.

Peggy: That's perfect though, because it's that corporate training.

George: Mission and vision. You have to come up with something, and then you have to do it. So we did.

Peggy: That's great.

Michael: This brings us up to the farm. Tell us what you do here, and a little history of how

you got to where it is today.

George: Wow. That's a winding road. The initial view was to plant lemons. In doing a bit of research we thought this was a reasonable place to grow lemons. They produce a lot of fruit per acre, and the economics looked reasonable for what we penciled out, and we thought it was warm enough. So in 1998 we did plant lemons on weekends and holidays, and began to take care of them, and in the process of this we realized the property was warm enough on the hills to grow avocados. So in 2000 we made our first avocado planting. We went up the learning curve for both of these crops. Then in the early 2000s, say 2002 or so, we began to learn how difficult it was not to grow lemons, but to grow and market them profitably. It's a great deal of work. We had trouble marketing the amount of production we could produce.

Michael: So it's easier to grow them than to sell them.

George: Oh yeah. Much easier to grow than sell. Everybody wants to buy a lemon, but they don't want to buy a lot of lemons. And we are too small an operation to sell profitably to a packing house. We're just too small to interest a packing house. We did try that one year, and decided not to do that any more.

Michael: How much production acreage do you have in the various crops?

George: We started with six acres of lemons and seven acres of avocados in 1998 and 2000. Currently, we have about eight acres of citrus total, and about 12 acres of avocados. In 2005, we decided to exit the lemon business slowly and switch to oranges. So we are in the process of interplanting and pulling out the lemons as the oranges get bigger. And we are continuing to plant small amounts of avocados. Hopefully this next year will be our final avocado planting. So we'll wind up with about eight acres of citrus and about 15 acres of avocados.

Peggy: So the oranges are easier to market for you?

George: Yes, they are easier to sell. As I said, everybody wants to by a lemon. But everybody wants to buy a bag of oranges, so it's a lot easier to sell them.

Beth: What we are growing is a navel orange. And our oranges are ready in the summer after the San Joaquin Valley oranges are done. So we have a little bit of a niche market because of our cooler climate right here. We'll probably be able to direct market a lot of them. They might leave in small amounts each week. Instead of marketing them all at once we may market them one bin a week. But that will also be a learning process, and may change as the trees get more mature and produce more. We've discovered that nothing's the same each year.

Peggy: The crop certainly isn't. The weather isn't. The market changes.

You were talking about the challenges of it and how George thrives on the challenges.

George: There's a lot of work to do. There are a lot of issues to solve. There's a great deal to growing a crop. Avocados require very close management of irrigation. The first couple of years that we grew avocados I over-irrigated and we lost a few trees to drowning. Some of the rain seasons in the early 2000s were big rain years. 2002 and 2003 I think, and we lost a couple of hundred avocado trees to drowning. They don't like wet feet. It was quite a bit of learning curve to determine how to plant the trees. We now plant them on berms and mounds instead of on grade as we did before. That way, there's better drainage and the trees survive. So once you've got them planted properly, you've got to irrigate them properly, which is not too much and not too little, but just the right amount. That requires learning. They don't produce much fruit until about the fourth year, but in the first several years we hadn't mastered the irrigation management issue and did not have very good production until about 2007, but that was a big freeze year, so we really didn't have very good production until about 2008 or 2009.

Peggy: What kind of avocados?

George: Mostly Haas avocados. But we have about 10% other varieties. Green skinned varieties such as Bacon, Zutano, Fuerte, and Reed, which are really good. But Haas are the gold standard. They are the primary fruit that we sell.

Peggy: I don't think I have seen a Reed.

George: Reeds are green skinned, a round fruit, and they're from maybe six ounces to 14 ounces.

Irrigation management is one of the problems. Nutrient management is another significant issue for growing avocados. They require a fair amount of nitrogen, and potassium, which are macro nutrients but they need the nitrogen and potassium at the right time of year. Also, they need zinc and other micro nutrients. Again, you need to give micro nutrients at the reasonable time of year also. It takes time to learn those.

Peggy: So you had to go through like field trials but it obviously requires a lot of research too.

George: Well, I wish we had done a lot of research before we planted, but a lot of the research was done in the process. We've learned by doing—by all the mistakes we've made. We learned how to plant by not planting correctly. We learned to irrigate by going to seminars and Avocado Society meetings, and by learning the hard way. And by observing. Other farmers have set practices, and you can see how well they do, or don't do, and compare that to how well you do in terms of production. You pay attention to your surroundings as well as to what you are doing on the farm.

Beth: There is a pretty good network in San Luis Obispo County, and opportunity for lectures and meetings. They bring up professors from UC Riverside who do research on avocados, and other specialists come in also. You've attended a lot of those meetings.

George: Oh, they're invaluable. The Avocado Society, University of California Cooperative Extension, they're excellent.

Peggy: Do you still have tangerines too?

George: Yes we do. In 2003 or 2004, whenever we decided that lemons were not the way we were going to make our living the next 20 years, we started experimenting with other trees—Mandarin oranges being one of those. So in 2005 I did an experimental planting with five different types of mandarins and three types of oranges. Several years later we were able to see which of those tasted good, looked good, and that we thought we could grow.

Beth: We also put in Meyer lemons, and there's a high demand for that on a local basis. It might be hard to market them on a large scale, but grocery stores will take a box a week or half a box a week of Meyer lemons. How many would you say we have now?

George: Oh, I think we have maybe 50 or 60 trees now.

Peggy: So George, you sell to local markets and Beth sells to farmers' markets. Talk about that a little bit.

George: Yeah. How to sell the fruit. You don't make any money if you don't sell the fruit. We first started to sell, I think in 2000, to the local Cambria Farmers' Market. That was kind of fun and kind of skinny too. I think it was $14 at the first market.

Beth: Well, when all you have is lemons, and as we said, people don't buy large quantities...

George: So we started selling at farmers' market, and then in 2004, when the packing house gave us such a terrible price for our lemons and we decided never again to sell to the packing house, then we still had thousands of pounds of lemons and nowhere to sell them. So I sat down at my desk and started cold calling the small independent grocery stores in San Luis Obispo County, and started to develop stores. Really small independents that would be interested in taking our fruit. I would take a box and give it to the produce manager. Generally those stores are receptive, and we developed a local direct market of about ten different stores that we sell our fruit to. Now they take our lemons, our navel oranges, our Meyer lemons, and quite a few take our avocados. The key being to have fruit of acceptable quality, and to have standard pack-outs, and be competitive on price—and to deliver when you say you will.

Peggy: I've seen it at Cookie Crock, and New Frontiers...

George: And Spencer's. Several of the Spencer's stores. So it's quite satisfying. We sell as much as we can that way.

Beth: A few restaurants take our products also. And Nature's Touch at Templeton. It's a small store that sells as much as possible local grown produce. It's like a mini Whole Foods. It's very small. But she's been a very good customer over the years.

George: It's been quite satisfying to develop relationships with people like the gal at Nature's Touch, and the produce managers at the various stores that we sell to.

Peggy: Beth, you do Cambria's Farmers' Market on Friday...

Beth: And Templeton on Saturday morning, and Paso Robles on Tuesday afternoon. And I'm seasonal. In the past I started in August, but now that we have all this citrus that's ready earlier, I've backed up to starting in May or June. I usually go into January or February depending on when the winter squash is gone. I'll stop Paso right at Christmas time.

Peggy: We know that you are allergic to squash. Yet everybody refers to you as the squash lady. How did that happen?

Beth: It's the New England in me. I grew up in Connecticut, and harvest time was just a wonderful time. I miss that aspect. It's taken me many years to come to terms with California and the lack of trees with color, and season changes. I've lived in California much longer than I lived in New England, but still there's a bit of me that still misses that. The very first year we put the lemons in I planted eleven mounds of jack-o-lanterns between the lemon trees. At the end we had this bunch of jack-o-lanterns, and we had developed a bit of rapport with

Farm Supply, because we were buying a lot of material from them to start the infrastructure on the property, and one of the people I talked to there said, "Bring them in. We'll buy them from you." So we had a Ford Explorer, and I loaded the back of the Ford Explorer with pumpkins and drove over to Farm Supply. They weighed the Ford Explorer and the pumpkins on their scale, and then we unloaded the pumpkins and they re-weighed it. They paid me, I can't remember...

George: $84.

Beth: It was eight cents a pound or something like that for the pumpkins and that was our very first sale from the farm. And then the next year we planted more between the lemons right up here and I started branching out, I tried the Rouge vif d'Etampes. How many years did we plant in the lemons, maybe 5? Four or five. And then my operation started getting bigger and bigger and I had to move out into the main field. And I started just developing all these different varieties because that's when heirloom pumpkins were just starting to come on the scene. Like heirloom tomatoes also were and it was really fun and exciting. The allergy part, I sometimes think it's because I've been in the plants too much and it's gone systemic, who knows?

Peggy: Like bees.

Michael: Yes. So you're the squash lady and we know you grow pumpkins. You grow a lot of squash and you've developed some kind of rapport with the restaurants in the county over this I believe, isn't that right?

Beth: Well one restaurant in particular, Robin's in Cambria, has developed a squash meal, a prix fixe dinner every October which they call "Smashing Pumpkins" and every portion of the meal has squash in it. It's not a meal I can eat unfortunately because it always looks absolutely wonderful. But this year the chef, Michael Wood, came out and walked through the fields with me and looked at all the different varieties and decided what he was going to make for each dish of the meal based on what he saw in the field and what we talked about and how they tasted. That's been a fun prospect. There's another restaurant in Paso, Artisan, that gets pumpkins from us on a regular basis.

Peggy: And they do a farm to table dinner, don't they?

Beth: They do a wonderful thing in the winter months, January, February, March on Monday nights they have a featured farmer and winemaker or winery and we go and talk. They make a portion of the meal with our product and use the wine from the winery that they're featuring and they ask us to go around and talk to people who are interested about our farm and our produce. So it's a fun evening, we've done it a couple of years.

Peggy: We've always wanted to go to Artisan's Monday night dinners.

Whenever we talk to you or see you we always kind of shake our heads and say you and George are two of the hardest working people we know. And I know we took daylight hours out of your working day George, so I guess my question again is, what keeps you going?

George: It's fun.

Beth: And George's favorite expression is "move it or lose it." It'll keep us active. George is one of these people who actually has to be active and busy and this will keep him occupied into his later years so to speak.

George: There's always a project to do here. Producing the food is very satisfying. Very satisfying to see a stack of boxes of your produce that you know is going off to market. I can't really describe that other than to say that it's very satisfying. You know you did that. There are also problems to solve, we have erosion issues and there are grasses to plant to control erosion and native trees to plant where they'll grow and there are lots of projects to improve the land. It's not just farming.

Michael: This triggers a thought in my mind. Peggy and I also go to the Farm Center meetings and we don't grow a crop on our property, but we watch all of you guys that do, trying to wrestle through all the regulations and the restrictions and the monitoring and all of the agencies that you have to keep up with. It almost seems like you need another degree to do this kind of work.

George: That's an interesting observation, and it's a fair observation. I think in the time that we've been farming, since the very late 1990's there's been a steady increase in the different state agencies that regulate different aspects of farming. Primarily in the water quality and water use areas and we have certain reports that we have to maintain. There are water tests that we have to do. We now are required to meter our wells and file reports on that. I think we report to two different water departments: State Water Resources Board and State Regional Water Quality Control Board, they're similar but different. Also any pesticide you use must be reported on a monthly basis which is logical. And there are other land use restrictions with what you can and can't do especially with regard to agricultural grading and setbacks and restrictions on pesticide use. Again many of which are quite logical. But in the ten plus years that we've been doing this there's been a steady advance of the restrictions and reporting requirements on farming.

Beth: We have found a couple of the agencies wonderful to work with. One is the NRCS and the other is the RCD.

George: That's the Natural Resources Conservation Service in Templeton and the RCD is the Resources Conservation District, also in Templeton. They have people, quite approachable, quite knowledgeable and available to farmers to help deal with some of the regulatory issues.

Beth: And they have information about erosion control and other issues that we face, that we all face on the Central Coast.

Peggy: They are a great resource. They have all those workshops. Michael, you did the erosion control.

Michael: I did one on designing farm roads for erosion control so that when you design a road it doesn't cause erosion problems.

George: So it doesn't wash out.

Peggy: But that's the thing that is so impressive. Between the physical work and the intellectual challenges and just coping with the compliance issues and having to be on top of all of that. How do you ever get away? I know you're going away for the holidays, but that's tough.

George: I like to say that it's hard to leave between growing and irrigating and frost control. It's difficult. But we do have a window of time in the spring that's after frost season and generally before irrigation season that we go away. Generally about March or so which is kind of nice. Now we think we can escape over Thanksgiving so that'll be nice too.

Beth: Last year it froze Thanksgiving morning or the day after but it's not going to this year. It's looking better.

George: I am pretty sensitive, going back to the comments about regulatory issues. We are quite involved. We do belong to the Farm Center and try to stay current on the rules and regs and the changes, but there are a lot of farmers—maybe they're not as tied to organizations like Farm Bureau—that aren't quite as current, and I think it's quite frustrating to a lot of people to deal with the kind of edicts that will come from the State. So there is a lot of room for conflict and improvement in these regulatory areas and communication, that's a big one.

Peggy: Your term as Chair of the local Farm Center, it runs through . . .

George: It's an annual thing it runs through January of next year and we'll have an election, if you know of anybody who wants to stand for Chair.

Peggy: No, so I was going to say do you plan to continue?

George: Yes, I plan to continue.

Peggy: Okay that's good!

George: But we're always receptive to people who might want to be Vice Chair or something.

Peggy: George you have a really nice way of working with all those different groups I think, and you have a really good understanding of the science behind things and as frustrating as it is, I think you can deal as best one can with the regulatory parts of it too, I mean that's extremely frustrating.

George: Sometimes the frustrating thing is not, it's just understanding what it is you have to do. Not doing too much, not doing too little but doing the right thing, and sometimes it's hard to understand what you're supposed to do. Sometimes it's one size fits all sort of regulations and that can be quite frustrating. And I'll just mention the one that really has got my goat right now and that's the current water testing for the Regional Water Quality Control Board. There are two aspects of it. We're all required in the Fall and this coming Spring to test for nitrates and it doesn't matter if your neighbor is one mile away or 100 yards away, he has to also test his well even if he's producing out of the same zone that you are and it turns out that we have zero nitrate in our well, yet my neighbor just a thousand feet upstream must also test his well at fairly significant costs to also show that there's zero nitrate in his water and again next Spring. And it's just sort of frustrating that the one size fits all rule comes down like that.

Beth: And there's been a request to have cooperative monitoring for the whole area but the conditions they're putting on how that cooperative monitoring would be done are such that the economics of it don't necessarily make it any better. We'd each have to bear about the same amount of cost.

Michael: And I know there are areas in the State where there are huge problems with water quality, the Salinas Valley and Santa Maria and some places where they do lots and lots of lettuce and lots of rapid and intense row crops and I can see what you mean about the one size fits all. This area is very different from that.

George: Cropping systems do vary a great deal from lettuce fields in the lower Salinas Valley to scattered avocado orchards in Santa Rosa Creek, so yes, things do vary.

Beth: Unfortunately for even organic growers they have a tiered system for this new program and you can be in Tier One if you're using a minimal amount of pesticides and if you're not using certain listed products, but if you're next to an already impacted stream—and they know which streams they are, they have them listed—even if you're an organic grower you might be in Tier Two, with more onerous requirements just by your location.

Peggy: So even if you're not contributing to it you're subject to it. And that was the thing about that whole set of water quality regulations—the way it was done. We went to that one meeting and the staff who wrote the regulations, it seemed like they were way over their heads. It was a real eye opener.

George: I think some of the staff in some of these State agencies may not have the experience level, the industry experience, the agricultural experience of the people that they're regulating. Many of them are much younger and don't have the practical field experience to really understand some of the implications or ramifications of the rules and regs that they pass, or seem to appreciate the costs, and yet these are real costs with real consequences. Hopefully what we do will lead to better water quality but I think that we could probably get there with less expenditure and cleaner regulation.

Michael: I'd like to shift gears a little bit. You live in the same Valley we do, Santa Rosa Creek, and there's quite a little social network here. You guys have a party, I heard a rumor that this might have been the last party, this last week, but tell us about the squash party you've been doing over the last few years.

Beth: Well the squash party actually started because of my allergy or sensitivity to eating squash and I was trying all these different varieties, different heirlooms and I really wanted some feedback from people and so we invited friends and neighbors over and I cooked all these squash and what I do is I just cut them in half, put them in the oven, bake them and then put them out on the plate with no seasoning, no butter, oil or anything and I gave everybody a form and they'd just go down the line and try them out. We've been doing this about 7 or 8 years and I got a lot of good feedback on varieties of squash and their tastes and I've developed over the years which varieties that I go back to and plant extra of because I can tell my customers at the Farmers' Market that these are really good ones. There really is a huge variation in winter squash from one type to another. So I did this and it's developed into a very fun neighborhood party, neighborhood and our friends, a few from town but a lot of people from the Santa Rosa Creek Valley come and it's a fun gathering. People bring food, bring wine and we just enjoy ourselves.

Peggy: So how did you find your place here? You said you looked for a year.

George: We did, when we decided, when the vision was to have a farm, it was to have a farm on the Central Coast where we could grow citrus. So I would take Fridays off from work over in Bakersfield and come over to the coast and drive the different canyons. We knew where the citrus belt was, which areas were warm enough.

Peggy: Tell us something about marketing the avocados.

George: It's not just the direct marketing farmers markets and local independent grocery stores that we sell our goods to. When we have a good avocado year which is often about every other year, they alternate bear. There's a good year, then a poor year, then a good year then a poor year. When we have a good year we have more fruit than we can sell to the local outlets and then we go to the packing house.

Michael: Some of your crops, I'm not sure about this but some of your crops have on years and off years on a cyclical basis isn't that right.

George: Yes, that's correct, primarily the avocados. Alternate bearing. Also an interesting thing, after the 2007 freeze, the January '07 freeze, we could see the echo of that until 2010. Things get reset by a big freeze and so you see your on year and your off year echoing down until you have another event like the heatwave or something like that.

Michael: Wow, I had no idea.

Peggy: This is an avocado question. When they freeze they don't totally die off, like Fred Gruber's (another Santa Rosa Creek Valley neighbor) trees came back?

George: Well it depends how cold it gets, you'll lose leaves or small twigs or medium sized branches up to an inch or so and I think Gruber lost branches to about an inch in diameter. In '07 we lost branches to half an inch in diameter, in the lower part of the grove.

Michael: In his case those inch diameter branches were trunks, those were new trees.

Beth: And the other thing that happens is to the stem, which is a pretty long stem holding the avocado onto the tree, it's not the avocado itself that freezes but it's that stem that freezes and they drop off as a result.

George: Or the blossoms are damaged. And when I say that you can see the echo we had a frostline through the middle of our orchard. Everything below the frostline was frosted and above maybe there was a little bit of frost damage but not very much and at the very top of the orchard there was no damage at all above 32. So the part of the orchard below the frostline had no production in '07, had production in '08 and yet above the frostline we had good production in '07 and no production in '08 so there was this part of the orchard was on and part of the orchard was off and that sort of levels out after a few years.

Michael: It seems like you could almost use that to even out your production.

George: If we could get even production or uniform production that would be very nice.

Beth: Growers have tried to do that, get half the orchard on and half the orchard off but there's always something in Mother Nature to reset the clock for them, like a freeze or a heatwave. It's been tried.

Peggy: Something out of your control happens. Tell us about the origin of the name Dos Pasos Ranch.

George: Dos Pasos. Well. We were living in Colombia in the mid-80's and Occidental Petroleum would bring in engineers from other operations. One of the things it did was to bring good productive people from say Peru or the U.K. or Argentina to an office that was expanding. And the Colombian office in the mid-80's was growing. We had a big new discovery that we had to develop and build a pipeline and develop wells. And so we brought people from all over, all different countries. And there was an Argentinian who was a drilling engineer that I worked with and he gave me the nickname of Dos Pasos which means two steps, and that just reflects that I took two steps for every step of his.

Beth: No not really, I realize now that it's because you have a very distinct walk, a long stride and you're not a particularly tall person but you were taller than anybody in South America as far as we could figure out and your stride was similar to the Dos Pasos horse in Argentina.

George: So it wasn't the long stride?

Beth: And it's from the gait of the horse.

George: Well, you learn something every day.

Beth: This is only what I've deduced but I believe that's why you got that nickname. It's based on the horse gait.

George: The other reason I think is because I have to do things twice before I figure out how to do them right.

Beth: But when it came to naming the ranch this was a bit of a problem because we really wanted to name it something geologic. And we tried everything, the formation that the ranch is on, the rock formation is called the Franciscan. There are parts of the Franciscan called melange and schist, there's serpentine, there's all kinds of things that make up this, but none of the names worked and the age was Jurassic. You know Jurassic Park would not work. So all of the geologic terms that we could come up with that really referenced the area just didn't sound right to us. The Franciscan didn't sound right and so in the end we named it Dos Pasos for George's nickname.

Michael: Very nice, I like it.

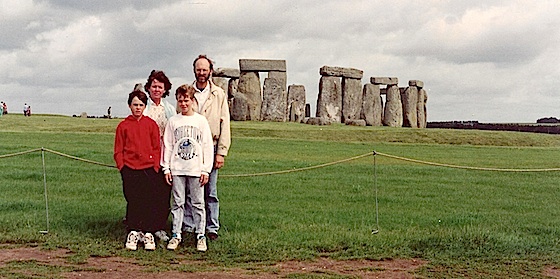

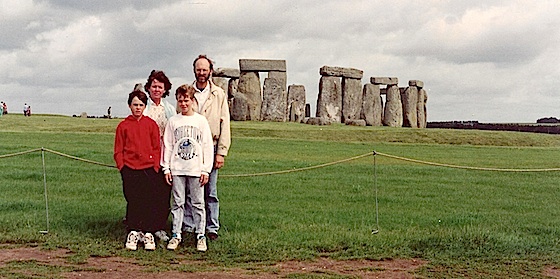

Peggy: So this is one of the things I wanted to go back to. You lived abroad in many different places, so talk about that a bit.

George: One of the reasons I wanted to work for Occidental in the first place was that they had overseas operations and I wanted to live overseas and have that experience. We both wanted that and so I was hired into the domestic organization and when I had an opportunity to transfer to the international division then I jumped at that and then I was able to go from there to get a transfer to Colombia. We had a heavy oil project in Colombia, so I got to go down there and get exposed to Colombia. And then when we had a large discovery in the Llanos in eastern Colombia they needed to staff the office and I had an opportunity to work on developing that oil field Cano Limon. And that took almost five years to ramp up the office, to drill the wells, build the pipeline, etc.

And from there we had significant operations in the North Sea. I was transferred to Aberdeen Scotland and we worked on the offshore fields in the northern part of the North Sea from Aberdeen.

And from there we had significant operations in the North Sea. I was transferred to Aberdeen Scotland and we worked on the offshore fields in the northern part of the North Sea from Aberdeen.

Michael: Did you develop a taste for Scotch while you were there?

George: Single malt's pretty good. Yes. Prince Charles and I both share a great fondness for Laphroaig.

Michael: So do I.

George: Good stuff. So anyhow we were four years in the U.K. What I like to say about the U.K. or Scotland is that we fit right in until we opened our mouths.

Peggy: Have you ever seen the movie Local Hero?

Beth: Yes and we actually have been in that phone booth.

Peggy: I love that movie. So after Scotland?

George: Well what happened there, there was an offshore problem on the Piper Alpha platform, basically a disaster and Occidental wound up selling its North Sea operations to the French, to Elf Aquitaine, the semi-national oil company of France. And many of us were transferred to the French company but I was fortunate to extract myself from that and wrangled a transfer to a new operation in South Yemen, where Canadian Oxy had a series of discoveries that they needed help developing. And so in 1992 I moved to Aden in South Yemen. And I was there for a year and a half before coming back to the U.S.

Peggy: And the boys were with you all that time?

Beth: Yes all that time. Our two sons and I stayed in Scotland for 6 months while George started in Yemen because there really wasn't a place for us to live. But once there was a place to live then we moved there and we lived there for a year with him before returning to the United States. We left when they were 4 and 5 and we thought it would be good for them to go to high school in the U.S. before going on to college.

George: So there were basically three countries that we lived in. Colombia, Scotland and Yemen. And they were all unique and different, very different and they were all special in their own way. I think Yemen was by far the most exotic. I loved it but I was glad to come home.

Peggy: And you both speak Spanish, was that from Colombia?

Beth: Yes, I studied Spanish because I had gone from working most of the time to being home all the time and I studied it and we use it everyday, both of us now. So it's a very useful language.

George: You also learned a bit of Arabic when we were in Yemen, enough to tease out road directions.

Beth: Just a few.

George: We went on some road trips in Yemen. We were there before . . . now I can't remember if North and South were unified.

Beth: Yes.

George: We were there right before the Civil War that started in March of 1994. We left before that happened.

Peggy: So what's next on your travel itinerary? Other than family holiday trips?

Beth: Another family trip to Philadelphia for a wedding. We think we'd like to go to Europe at some point and see some old friends from our days of living in Europe and I would love to see parts of southern Europe. I haven't seen Spain and Portugal and I've not seen Greece and Italy and I'd love to see that. When we lived in Great Britain we traveled to Germany and France and the Netherlands.

Peggy: But citrus country! Spain.

Beth: Yes but I would love to see some of the Mediterranean region.

Michael: That sounds like a business trip.

Beth: That would be good wouldn't it? Lemons in Italy. Limoncello.

Michael: We always like to end with a specific question. What would you tell a person who is doing something like what you've done? What's your advice to someone who is fresh and wet behind the ears and has this big vision to do something crazy like this?

George: Good question. I have to think about that a little bit. Quite a few things I suppose and I'll just sort of say them. I would say know what you want to do to the extent that you can and realize that whatever you plan will likely have forces pushed onto it that will lead you in different directions because it's hard to have a straight line plan and to know it in advance.

Beth: In farming.

George: At least in farming. That's one. The second is, try to be sufficiently capitalized so that you can do it. Try to buy or lease land that has good water and the climate that you want to the extent that you can know the climate that you need and the soil that you will need. Some of what we're doing we did not anticipate. I did not anticipate avocados when we purchased this. We're fortunate that we have some exposures and some elevation that we can grow them.

Beth: And the water.

George: The water is very, very important, especially in California.

Beth: And I think you have to understand that what you're getting into is a huge amount of work and it just requires a lot of hands on time unless you have enough capital to pay other people to do it for you. But for us that wasn't the issue. We're doing it because it's a lifestyle that we wanted, that we really like, and the working outside and working on the farm is part of the lifestyle that we wanted.

George: I think I would also say that I would not try to get ahead of yourself. In other words if you rush too fast to try to do something you may find out that you can't do it because you don't have the capital or that there are things that you haven't learned about in the agricultural process, marketing.

Beth: Networking is always good. We might not have put lemons on the flat if we had talked to the right people. Some of the people who grew up in the area and know much more about the climate. We had input from a former farm advisor but he didn't live in this valley and he didn't have intimate knowledge of what the weather's really like and if we had met some of the people that we've met since who could tell us more about the weather we probably would have backed off from lemons.

George: Or might not have been quite as aggressive with lemons in the beginning. I would say be patient and bide your time if you can, but don't be so patient that you don't try it.

Michael: Well you both have qualified your statements as being about farming but my impression from what your saying is that it applies to anybody who's doing anything that's a little outside the lines. Almost everything you've said with the exception of a few of the details about things like weather and trees and that sort of thing, applies to artists, applies to anybody who's doing any kind of a small business where you have to make it up as you go. You have to figure out how to make it happen.

Peggy: Well it's about creating a new life for yourself, basically you did. You were in Bakersfield, you were working for a company and you started a whole new life here.

Beth: And it's a life we really enjoy. We love being here.

Michael: We've noticed. Is there anything else we need to talk about?

Peggy: And Michael referred to it as a crazy business, but I think a lot of us do envy you or you've set yourselves up in a way that people would envy you. You've made this choice, you're making it work, you have a beautiful home, you have a beautiful ranch and you both seem to be thriving on the life you've chosen.

Michael: Before we go I want to have you tell us a little bit about your house. It's not the average everyday house.

Beth: Well our house basically looks like a southwest house I would say, but we lived in Colombia. Scotland doesn't really figure into it but we lived in Yemen and there's a lot of architecture that we liked from those regions, and they're really all connected through history, the Moors to Spain then on to South America and Central America and into the Southwest. And the house is partial straw bale and it has a tile roof and is incredibly well insulated so that we very rarely turn the heat on. We had a great builder and supervisor when we were building who understood what we wanted it to look like. We had a great architect who also did. So it was a good mesh in the building process of getting what we wanted.

Peggy: Whose idea was the straw bale?

Beth: We talked to the architect and in the end he was the main one. We were looking at alternative, either rammed earth or the styrofoam building, things that were . . .

George: Alternative building construction that was well insulated.

Beth: Good insulation, energy efficient house, and it is that. It's worked well.

George: We were looking for a good living space and floor plan at least in the main part of the house is really quite open. So you walk around and feel the space.

Michael: And you have solar panels on your pumps?

George: Yes in '09 we put in solar electric to run the irrigation wells and so far that's working pretty well. And some day if they get a proper functioning electric vehicle we'll get solar panels up here to charge the batteries.

Beth: Because our house doesn't use enough electricity to warrant putting in solar. We don't have air conditioning, we don't need heat.

Michael: Well I think we've covered a lot of ground.

Beth: It'll be interesting to hear how all this all comes out, hearing our life go before us.

Our monthly radio show: Designing a Creative Life

|

And from there we had significant operations in the North Sea. I was transferred to Aberdeen Scotland and we worked on the offshore fields in the northern part of the North Sea from Aberdeen.

And from there we had significant operations in the North Sea. I was transferred to Aberdeen Scotland and we worked on the offshore fields in the northern part of the North Sea from Aberdeen.