This month in Outside the lines

Here's a sneak peek at what's inside for December, 2011.

Peggy's Progress

(Not to be confused with John Bunyan's tale of agony and doom!)

Christmas Day installment.

Uh oh, you caught me. I confess. I am a total slacker. It's been two months since I first wrote about embarking on my creative path. The trouble with publicly stating my intentions is that I have to admit just as publicly that I have made no progress whatsoever, zero, zilch.

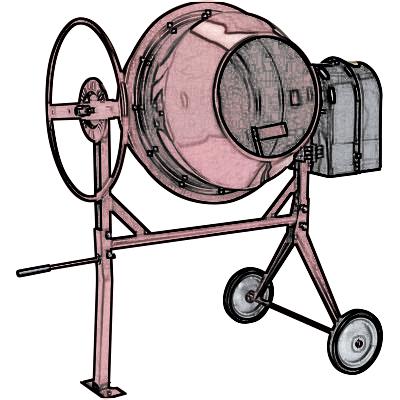

Did I tell you before that I wanted to play with concrete? And did I? No, not exactly.

I did manage to get to the library to get some books on how to work with concrete and how to get the creative juices flowing. That selection of books gives you an idea of just how easily I can get stuck. I love pouring through the pictures for design ideas and recipes for what mix of concrete to use for structural versus decorative pieces. As usual, I research and study up on methods, techniques, and how-to's but I never just get in there and get my hands dirty and do it. For some reason I think I have to have a complete idea or design in my mind before I tackle a project. With no defined ideas and no designs the project is a non-starter.

It's easy for other things to take priority since I didn't commit the time, or allow myself the time to devote to a project just for me. Oh and here's another good one. I told myself I shouldn't be spending money and didn't have the cash to go buy the supplies I need. Never mind the fact that a sack of concrete (a big sack at that) costs about $4 and Home Depot is 2 miles from work and on my way home. Trying to be more creative is not unlike trying to lose weight.

One of my other library selections is Julia Cameron's

Sound of Paper .

For those of you who aren't familiar with her, Cameron is a prolific and inspiring writer whose many books offer encouragement .

For those of you who aren't familiar with her, Cameron is a prolific and inspiring writer whose many books offer encouragement

along with quick and easy tools to spark creativity and imagination. "The Sound of Paper" is an easy read but it's probably more useful as a refresher course and companion to Cameron's classic,

The Artist's Way

along with quick and easy tools to spark creativity and imagination. "The Sound of Paper" is an easy read but it's probably more useful as a refresher course and companion to Cameron's classic,

The Artist's Way ,

which she wrote 30 years ago. ,

which she wrote 30 years ago.

The Sound of Paper offers simple tools that get to the heart of the resistance I experience on my path to creativity. Many of these tools are also available on Cameron's website. One of the staples of her work is to schedule "Artist Dates" for yourself.

"An Artist Date is sacred time. It's time set aside to nurture our creative consciousness. Think mystery rather than mastery. Think pleasure, not duty. Choose an expedition that enchants you, one that truly interests your inner explorer. In planning and executing Artist Dates you should expect to encounter a certain amount of inner resistance...Commit yourself to overcoming your resistance."

Such dates can be visiting a gallery or museum, or browsing through an art store or thrift shop. Now hear this! I hereby commit to an Artist Date with myself on Tuesday, December 27th, 2011—to explore the great outdoors and gather some plant materials to play with, maybe for some sort of winter decoration. I'm off from work next week, so no excuses this time. And now that I've committed to it here I'll have to provide proof for you next month—so watch for photos of my exploration.

My other resistance point is procrastinating by pretending to study up on, for instance, how to work with concrete...

Here's the subscriber link to the full December 25 installment.

From the December 18 installment.

Let's talk about exposure. Your exposure. There's no better way to get exposure than to do something that's hard to ignore and highly visible to your entire local community. What follows is a story in progress about a small group of artists who are doing just that. It's called "the phantom project", and it's happening right now as I write this in San Luis Obispo, California. I will tell the story in first person, because I'm the original instigator, and lead the team that's doing it. As I tell this story, I want you to think about the principles of innovation and creativity involved more than about the actual details.

Let's talk about exposure. Your exposure. There's no better way to get exposure than to do something that's hard to ignore and highly visible to your entire local community. What follows is a story in progress about a small group of artists who are doing just that. It's called "the phantom project", and it's happening right now as I write this in San Luis Obispo, California. I will tell the story in first person, because I'm the original instigator, and lead the team that's doing it. As I tell this story, I want you to think about the principles of innovation and creativity involved more than about the actual details.

This is not the story of Erik, The Phantom (Lon Chaney) and Christine Daaé (Mary Philbin) in the image to the right. The phantom project is conceptually simple: an art show pops up on short notice in vacant retail space, runs about a month, then vanishes as quickly as it sprung up. Then it happens again, and again... The location is never known more than a month or two in advance because of the nature of real estate vacancy. Over time, the local art community grows familiar with the concept and embraces it. That's the idea anyway, and I'll bring you along for the ride as we see how it unfolds. So here's part one.

The idea seemed a bit scattered and disjointed at first. Several of the artists we talked to early on were skeptical. It would be too much work. How would we find spaces to show in? What about the cost of setting everything up, and of publicity? What if there weren't enough volunteers to do it? How would we get the support we need from the local art associations? What if nobody showed up?

We decided to prove the skeptics wrong first, then invite them to join us later...

Here's the subscriber link to the full December 18 installment.

Finding Your Audience

Here's a clipping from the first article in the December 11 installment.

When we interviewed Randy Stromsoe for last week's installment of OTL, we wrapped up with a question that we ask every time we interview an artist.

What would you tell somebody that’s just breaking in and trying to make an art career happen?

We always get interesting answers to that question, and what Randy had to say was no exception.

"I think I’d find what show fits your work. It’s easy to get excited if you have an arena where they like your work and you’re a celebrity. If I just tried to make it in Cambria or San Luis Obispo, I would have been so frustrated. If I never took a chance and went to the East Coast then my life wouldn't have worked out. You have to find these arenas and so much of it is word of mouth by talking to other artists and looking at their brochures and what work they’ve pushed before...

Some areas sell a lot of what we do. If I go back to Philadelphia to the Museum of Art's Craft Show I have more buyers than anywhere else. They also promoted me more than anywhere else. That show has been really good to me and the people who go to those shows have bought a lot."

The natural inclination of most of us is to start small, start local, and build up and out from there. That intuition works for a florist shop or a jeweler or a service business like swimming pool service, dry cleaning, or auto repair. But art is a little different from most other businesses. An artist is working with a product that has very specialized and intangible appeal. There are regional differences in taste and interest, and the general public in most towns has little understanding of the pricing and value of art.

Add to this the fact that many of us as artists choose to live where our environment is conducive to our creativity rather than where our natural market is. Windhook, for example, is on the central coast of California in one of the most amazing geographies and climates that we know of. We located here because the creative energy of the place works for us. But San Luis Obispo County is not a major art center. We do have several good art organizations here, and a higher than average concentration of good artists than many places of comparable size. But this does not equate to a local art market strong enough to support all those good artists.

Of course this is not to suggest that you ignore your local market...

In addition to the rest of the article quoted above, there was a second article in this installment about the role that galleries and artist's representatives can play in solving the puzzle of finding your natural market. You can get to both of these articles and all the rest of our member resources when you activate your full subscription. We hope you will join us soon!

Here's the subscriber link to the full December 11 installment.

The Windhook Interview—Randy Stromsoe

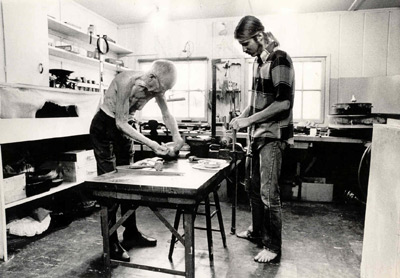

From the December 4 installment.

This month's interview is with classically trained and internationally known silversmith, Randy Stromsoe. We join the interview already in progress.

...Michael: You were 19 when you started to work for Porter Blanchard. That must have been around this time.

Randy: Yeah. She had a field trip to Porter Blanchard’s shop. There must have been 30-40 students there.

We pull up, and Porter’s out there, dress slacks, dress shoes, and no shirt. He was real excited to show us everything. You walk into his shop and he has his father’s tools and his uncle’s tools—it was like stepping back 100 years. He had all these wood forms and leather forms and anvils.

Peggy: Where was this?

In Pacoima, off Laurel Canyon Blvd. He had 10 acres, orange orchard, boat shop, chicken coops, a couple of houses and swimming pools, and when he died we were making a boat. He was 84 but he didn’t know he was 84. He didn’t look in the mirror much. He just got on with life and he liked young people because they’re full of life. So he was raising an oval vegetable platter and he had some of us try it. After I got done he came up to me and said, “How about coming to work for me.” What he didn’t know was I was the only person in the class that had tried the technique, so before this, I had already mutilated a couple pieces of copper and couldn’t seem to make it work. But when he was explaining it to us I had one of those moments—oh! now I know what I needed to do. Those other guys didn’t have a chance.

Michael: So that was your big break.

I knew this was a big opportunity in my life. I asked if he paid and he said, “yes, I pay.“ Zella was trying to get me hooked up with her master and that wasn’t a paying job. You had to pay him $3000 a year and you had to go there and pay your own room and board and pay him for 3 years, the 4th year was free and the 5th year he paid you. So four years without any pay and I looked at her and she looked at me and said, “You’re pretty lucky.” So I jumped at it.

How many 19 year olds get to butcher a piece of silver and stamp their master’s name on it and have people buy it? You know I went back a year or two later and looked at some of the pieces I made for some of the stores in Westwood and Beverly Hills and some of them were terrible. You cannot become a master silversmith in your first couple of months. You have to pay the price. You’re not going to be doing quality work that quick.

Peggy: So Porter died when?

Randy: Somewhere around 1973.

At the end Porter was in the hospital. I was his bookkeeper and I was getting these ideas, and we made up all these new products. We changed what people were doing. We went down some bad avenues, but we were young—we didn’t know. We did some real time consuming pieces, that had hammer marks, bright polish, handmade handles, some chasing and fluting and real cool wrapped things. They were selling and we were making good money. Then all the companies on the East Coast—Reed and Barton and others started copying us. They’re copying this Porter Blanchard Company stuff. They think it’s this old master making it and it was just these 20 year old guys. We were shaking things up, taking chances.

Michael: I want to dig into the concept of apprenticeship. Does it have a place today?

Randy: Well, yes and no. Realistically, an art organization or program of some kind should be paying the artist to have an apprentice. In most cases, at the Porter Blanchard Company when I was there I worked with maybe 20 different workers and I don’t think any of them are silversmiths now. All of them had good potential but most of them get a few years behind them and want to go out on their own. So you’ve been paying them while they’re learning and they’re messing up everything that they do, so you’re losing money and then they finally turn around and leave.

Peggy: Some countries have sponsored programs where you go work with a master—scholarships, or fellowships.

Randy: Seems like in this country we’re down to a handful of people who know these skills. We need apprentices. And we have university programs, but we’re losing a big step. And the only way I could do it is if someone payed me. I was amazed that Porter paid me as much as he did. But at that point any thing he turned out people would buy and we had a waiting list of orders. So it was a little easier.

My teacher, Zella Margraff always got different apprenticeship grants and it didn’t cover the whole price but she’d show her body of work and her apprentice’s body of work. She’d teach and get like a $10,000 grant. I know with the internet now you can find out more about things coming up than you could 5 years ago. I have everything set up. I have it set up like the old shops did. I just need an open mind, somebody that can take it all in.

Peggy: How have things changed?

When Porter was my age he was dealing with a handful of families that were buying everything he made. 15-20 years ago my customers had a list: a water pitcher, a coffee pot, a creamer, an ice bucket, serving pieces, candlesticks, a vase, some big bowls, and some salad bowls. They didn’t get just one piece. If you got a customer, you got a customer for years to come. Nowadays that doesn’t exist.

A lot of the connoisseurs, a lot of the collectors, a lot of the museum people don’t know how to appreciate silver. You can see that with appraisers, like on Antiques Roadshow—silver is always way down there. People think that the sleek and unadorned images are simpler to make but in a lot of cases making something simple and elegant is as much or more work than a lot of decoration. There’s a lot of craftsmen that wouldn’t be able to make a sleek piece. There’s some people who really know what they’re looking at but the appreciation of everything’s really gone kind of crazy.

And now in the jewelry industry they’re figuring out all these gimmicks and instead of hammering out a piece you could have this device do it, and if you get enough equipment, you can make a lot of products without much craftsmanship. And they sell the metal clay now, a clay they can put in the oven, 500 degrees and it comes out metal. It doesn’t take any craftsmanship. It’s getting to be more a hobby thing. In the old days to be a silversmith took 5 to 7 years.

There's much more of Randy's interview. Here's the subscriber link to the full December 4 installment.

|

Let's talk about exposure. Your exposure. There's no better way to get exposure than to do something that's hard to ignore and highly visible to your entire local community. What follows is a story in progress about a small group of artists who are doing just that. It's called "the phantom project", and it's happening right now as I write this in San Luis Obispo, California. I will tell the story in first person, because I'm the original instigator, and lead the team that's doing it. As I tell this story, I want you to think about the principles of innovation and creativity involved more than about the actual details.

Let's talk about exposure. Your exposure. There's no better way to get exposure than to do something that's hard to ignore and highly visible to your entire local community. What follows is a story in progress about a small group of artists who are doing just that. It's called "the phantom project", and it's happening right now as I write this in San Luis Obispo, California. I will tell the story in first person, because I'm the original instigator, and lead the team that's doing it. As I tell this story, I want you to think about the principles of innovation and creativity involved more than about the actual details.